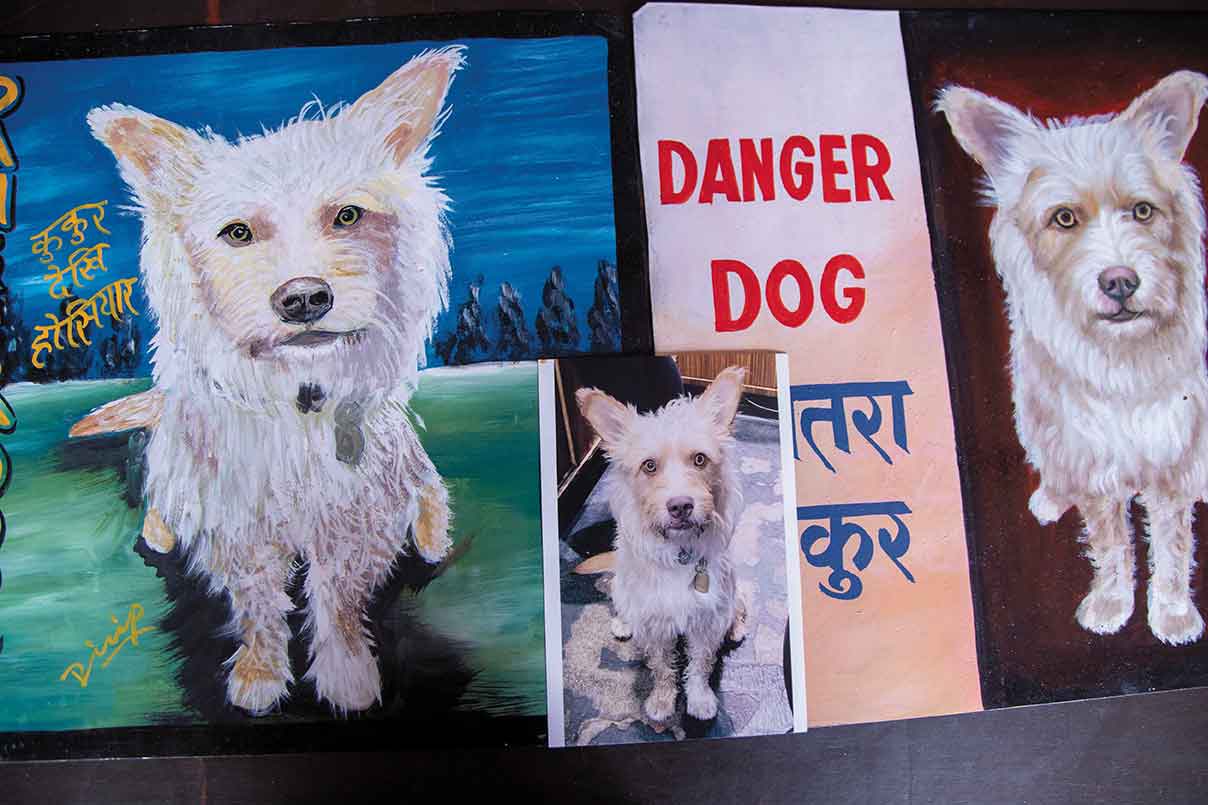

Popular cartoonist Rabin Sayami says a lot and then some with his satitical sketches

Soft spoken and calmly humorous, followed by a satirical smile, is one way to describe Rabin Shayami in under ten words.

Now, who is he? Rabin Sayami without a hint of an ego calls himself amongst the first generation of professional Nepali newspaper cartoonists. You know, the ones who make sharp stabs at the day’s events, using the power of satire and cartoon sketching—a politician’s slip-up, war, disaster and many happy events too.

Now, who is he? Rabin Sayami without a hint of an ego calls himself amongst the first generation of professional Nepali newspaper cartoonists. You know, the ones who make sharp stabs at the day’s events, using the power of satire and cartoon sketching—a politician’s slip-up, war, disaster and many happy events too.

Rabin’s journey began at the early age of 16 with the Newari digest Sahalaher, making non-political cartoons. After completing his S.L.C from the British Council, he studied science. Surprise, he didn’t enjoy it and soon dropped out. A worried father asked him what will you do now? And took him to a mechanic friend, to learn a trade. Again surprise, the artist was not in love with that trade either. Once more a worried father asked what will you do? I will live by my cartoons; his father was not so convinced. At 19, Rabin published his first satirical and political cartoon with Dristi, a weekly paper, receiving the un-handsome sum of 300 rupees. His work was so warmly accepted that by his third published piece, he was commanding 1,000 rupees! Soon, his father’s tone warmed, becoming “very proud” of his son.

Sitting with Rabin becomes a small education in the history of Nepal’s publishing world. His time started in 1990, just as Nepal’s old system of governance: the Panchyat System, was being replaced by a democratic one. With that the freedom of press and expression was being allowed. Before that, nobody could question the monarchy, so there was definitely no such thing as satirical cartoons. Except, recalls Rabin with great humour, during the festival of Gai Jatra (Cow Festival) which celebrates the lives of the deceased humour, could those images be published.

Rabin tells how in the days before technology his cartoons used to be made on a zinc block the day before printing began and those plates needed a day to dry in the sun. And, if there was no sun, which is common in rainy season, then his cartoon would not be printed!

Rabin finds himself asked often about where the new generation of cartoon artists are? He wonders this himself too. He declares that in India, you can find many artists, yet here the next generation is sparse. Rabin can only surmise that it is not easy to find people who can both sketch and think. There seems to be a lack of people who can punch a thought home within the confines of a sketch within a short time.

Rabin finds working at home more productive than in an office. So after his meals, he retreats to his studio with the day’s newspaper to search for ideas. Once he finds one, he spends time enhancing it, only then does the sketching begin, followed by the filling in. This can take an entire day.

This artist does not believe it ever possible to change his job, he feels like he could not survive without this work in his life. It seems like he has no good reason too, with work aplenty from agencies such as the Red Cross, UNICEF and Save the Children, looking for his special touch, as well as demands from publications.

As he is now expecting his first child, I ask would he be happy for him or her to become a cartoon artist? Rabin Sayami smiles his satirical smile and says his child would receive every support.