Figure 1. Mt. Makalu (8481 m), Makalu-Barun National Park and Buffer Zone, Nepal (photograph by A. Byers).

Introduction: Between October and November, 2017 I spent 26 days walking across the Makalu-Barun National Park wilderness area in eastern Nepal, from the village of Khandbari in the east to Lukla in the west. I had been intrigued by this little known trek since the early 1990s, when I worked as the first Co-Manager of the then-new Makalu-Barun National Park, established in 1992 through the joint efforts of the Government of Nepal and The Mountain Institute (TMI)(www.mountain.org). Between 1993 and 1995 I lived with my young family in the village of Khandbari in a traditional, two-storied thatch roofed house, with pigs, chickens, vegetable gardens, and beautiful views of the Jaljale Himal from the veranda in the evening.

One day at the office, I found a sketch map of the new park and buffer zone in one of our tourism development brochures that clearly showed a trail that crossed the entire wilderness area (Figure 1). Trouble was, when I asked about it, nobody really knew where the trail was, nor who the cartographer who drew the map was so that I could ask him or her what their information sources were. I knew that in 1977 the anthropologist Johan Reinhard and mountaineer Yvon Chouinard had made a winter traverse of the park, from Saisima to the Hongu Khola valley and over the Amphu Laptsa into the Khumbu, following their study of the sacred Khembalung caves near Dobotak. But that was 41 years ago, and Johan couldn’t remember the exact route that they had taken other than “going up a very steep ridge out of Saisima and then down to the Hongu valley.”

Regardless, work, family, and the end of my tour in Nepal intervened, and I put the idea of walking across the Makalu-Barun wilderness on the back burner. We returned to the US in 1995 where I continued my work at TMI, splitting my time between the development of research and conservation projects in the Andes, Appalachians, Himalayas, and elsewhere in the mountain world.

Figure 2. Makalu-Barun National Park and Buffer Zone. The red line traces a trail that the1990s map depicted as traversing the entire national park.

Fast forward 27 years. I’d recently started coming back to the Barun valley in the northeastern part of the park, in 2014, 2016, and again 2017, on different research expeditions funded by the National Geographic Society and the National Science Foundation. This time, October 2017, I was back with a team of teenage Rai porters, earning some extra money over the Dasain holiday, determined to find this elusive trail and cross the entire Makalu-Barun wilderness area by foot. Trouble is, nobody knew where the trail was from the edge of the Hongu valley ridge down to the Hongu river. Nor if, once we got there, there’s a bridge to cross to the other side.

And so began the journey of uncertainty and change. Uncertain because we were venturing out into a wilderness area with only a vague sense of how to get to the other side. Change, because so many things had changed throughout the region since I had lived there in the mid-1990s.

Change: Khandbari in those days, for example, was a sleepy bazaar town with no paved roads and no power lines, four hours walk from the grass airstrip at Tumlingtar. Tumlingtar itself was a three day walk from the nearest road. It was an exciting time to be living in the region and working with the project’s Nepali and western staff, testing new models of local participation in protected area management initiated by Daniel Taylor, then the CEO of TMI, with the full support and encouragement of his Harvard college days friend, the late King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah. Makalu-Barun was the first national park to be nearly surrounded by a conservation area, and the first to hire local people as Game Scouts and Rangers, including the first female Rangers, instead of using the military for patrolling purposes. During the 1990s the project implemented dozens of innovative projects that promoted cultural conservation, biodiversity protection, ecotourism, and the marketing of local handcrafts (e.g., lokta paper, allo cloth, bamboo implements), to name a few. This all changed with the Maoist insurgency between 1996 and 2006, during which nearly every building and trace of the Makalu-Barun project was wiped clean off the face of the earth.

Figure 3. Weaving allo cloth, made from the fibers of stinging nettle (photograph by A.R. Sherpa).

But that’s not the only thing that had changed. By 2010, the demand for cheap labor in the Middle East and Malaysia had resulted in the outmigration of thousands of young Nepali men each year from the region, leaving behind villages that were now populated by older people, young children, and single wives. Livestock populations had plummeted, reportedly a result of the new labor shortage; plus the fact that more children, a key component of the labor force in the 1990s, were now attending school; and changes in preferred lifestyles, since spending months in a high altitude, cold and rainy Goth was not exactly the younger generation’s idea of a good time. Climate change, a phenomenon totally off our radar screens in the 1990s, had led to the formation of new, massive, and potentially dangerous glacial lakes and hazards to downstream life and infrastructure, such as the April 20, 2017 glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) in the Barun valley that killed over 30 yaks, scoured the river channel to bedrock, and destroyed dozens of bridges and structures (https://nepalitimes.atavist.com/high-water). The construction of unpaved roads in the region had brought positive, negative, and uncertain changes—access was now better and food was cheaper, but roads tend to generate strip towns, garbage, and are often abandoned after a year once they become impassable due to a lack of maintenance. Finally, the curious “moth-plant” yartsa gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), which can demand prices of up to $50,000.00 per kilogram in China depending upon size, aroma, and region of origin, started being commercially harvested in alpine valleys of the Makalu-Barun region around 2003, bringing thousands of collectors per year to remote and high alpine pastures historically visited by only a handful of livestock herders and pilgrims per year.

But some things had not changed. Makalu-Barun is still one of the most wild, beautiful, biologically/climatically/culturally diverse regions in Nepal. Vegetation ranges from subtropical

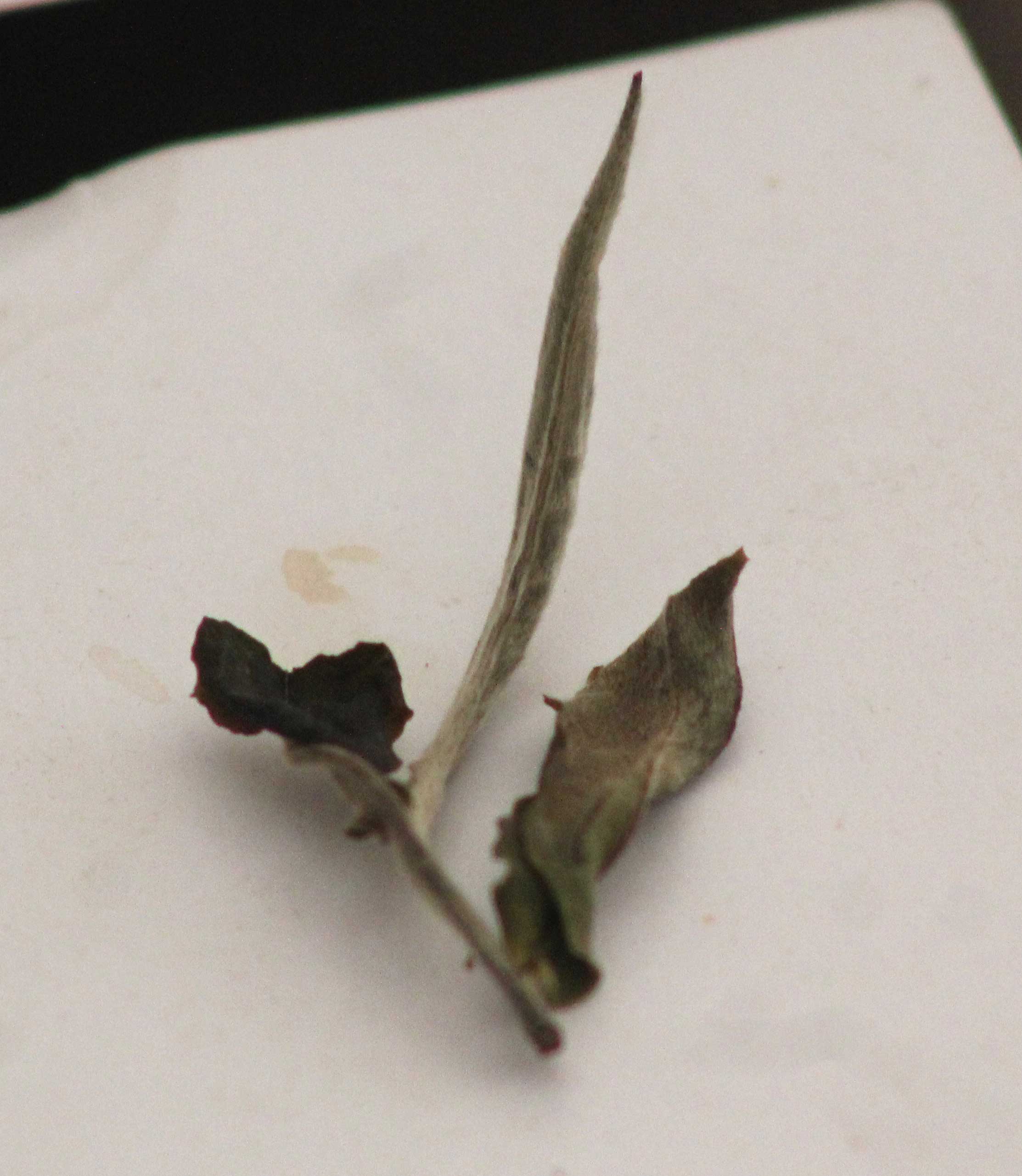

Figure 4. Yartsu gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) from the Makalu-Barun region is smaller and less valuable than that found in other places such as Dolpa, but still provides a good source of supplementary income to livelihoods based on tourism, agriculture, and animal husbandry (photograph by A. Byers).

Sal (Shorea robusta) forests at elevations below 1000 m; temperate zone oak/maple/magnolia forests between 2,000-3,000 m; fir/birch/rhododendron forests in the subalpine between 3,000 m to 4,000 m; the herbs, grasses, and dwarf rhododendron/shrub juniper of the alpine pastures between 4,000-5,000 m; and nival or snow and ice zone above 5,000 m. Thousands of kilometers of latitude squeezed into six kilometers of altitude.

The park, which receives more than 3,000 mm of precipitation per year, contains more than 3,000 species of flowering plants that include 25 of Nepal's 30 varieties of rhododendron; 48 species of primrose; 47 species of orchids; 19 species of bamboo; 15 species of oak; 86 species of fodder trees; and 67 species of economically valuable medicinal and aromatic plants. Wildlife include some of the densest populations in Nepal of the red panda, snow leopard, musk deer, barking deer, clouded leopard, Himalayan black bear, wild boar, and serow. Ethnic groups consist primarily of the Rai and Sherpa, with populations of Gurung, Tamang, Magar, Newar, Brahmins, and Chetris in the lower altitudes. Since the 1950s, a number of expeditions in search of the Yeti have been launched in the region, based upon the theory that the rugged terrain and impenetrable forests of the eastern Makalu-Barun region would provide the perfect cover and habitat for a creature not wanting to be found. Aside from a few tracks in the snow photographed by ecologist Edward Cronin in the early 1970s, however, little real evidence for the existence of the creature has been found. Most experts now agree that tracks found in the snow by Shipton, Cronin, and others since the 1950s were made by the Himalayan black bear through a process known as “direct registration,“ i.e., the back foot is placed precisely over the front footprint, creating a large track that appears to be bipedal and human-like.

In spite of its spectacular biophysical and cultural diversity, however, the park has received little in the way of tourism when compared to most other mountain parks in Nepal. Between 2010 and 2015, for example, the Government of Nepal records an average of only 1,027 trekkers and climbers per year to the entire Makalu-Barun National Park, with the vast majority attempting to climb Mera Peak (6,476 m), Nepal’s highest “trekking peak,” located in the drier western region of the park. Only a couple of hundred trekkers and mountaineers visit the Barun valley and Makalu basecamp per year. Lodges, which have only been constructed since the end of the insurgency in 2006, are still quite primitive, and food varieties and quality limited, certainly when compared to those of Nepal’s other national parks. Nearly 30 years later, I was to find that Makalu-Barun still remained a hidden green jewel among Nepal’s protected areas, containing an enormous potential as a nature-based economic development asset for local communities if only development of the adventure tourism trade could be initiated.

The Journey: The journey began with a jeep ride from Khandbari down to the village of Heluwa on the Arun River, stopping halfway down at a village named Ratimaati because the road was too muddy to proceed any further—due to no maintenance, I might add. Just for fun, while chatting with our jeep driver on the way down, I asked him if he knew an old friend of mine from the 1990s, Bhakta Ram Rai. Bhakta was a farmer, yak herder, and former shikari (hunter) who had an incredible knowledge of jungle lore—how to identify animal tracks, scat, edible/medicinal/utilitarian wild plants, birdcalls, how to make cordage from natural materials, how to survive in the forest with just a kukri and some salt, and on and on. I had met him after sending out word that I was interested in hiring former shikaris for one of our natural history projects, since I knew by experience that hunters are usually among the best naturalists to be found. Once Bhakta and others understood that I wouldn’t throw them in jail for being former hunters—a widespread rumor at the time, I later learned, since why else would the park’s Co-Manager want to meet with shikaris?--we were to spend weeks together in the forests of the Makalu-Barun wilderness area over the next two years, immersed in jungle lore, making plaster casts of mammal tracks, identifying birds and bird calls, and documenting traditional trapping methods.

“Sure,” said the driver. “He’s my uncle.”

Figure 5. Low altitude rice fields adjacent to the village of Heluwa on the Arun River, near Bhakta Ram Rai’s house (photograph by A. Byers).

Figure 6. Bhakta Ram Rai in the mid-1990s, holding a Jack in the Pulpit corm that a pheasant had eaten (photograph by A. Byers).

I couldn’t believe my luck, especially after having no contact with Bhakta for 27 years. The next morning I was talking to him by cell phone (another thing we never dreamed of back in the mid-1990s), and he said that yes, he knew the trail, but that he was in Dharan getting a tooth pulled and wouldn’t be able to come with us because he needed a week or more to recover. But he said that a friend of his from Tamku, Pasang Sherpa, knew the way and could guide us across the wilderness and down to the Hongu valley.

So once in Tamku we found and hired his friend Pasang Sherpa, originally from Dobotak but now living north of Tamku where the schools were much better, he said. As it turns out, Pasang had been the research assistant and guide for a number of western graduate students working on their Ph.D.s in the 1990s, such as the ornithologist Jim Bland; medicinal plant specialist Ephrosine Daniggelis; and geographer/forester Chris Carpenter and Bob Zomer. He still works occasionally as a climbing and trekking guide. We also hired two other local guides at his recommendation, one of whom, a former Makalu-Barun Game Scout, said that he had been as far as the overlook to the Hongu valley the previous summer searching for yartsa gumbu, and knew of a trail down to the Hongu river. Everyone felt confident that we’d find the trail once there. Things were looking good!

But one thing was already abundantly clear--this trek was different. In the Khumbu, Langtang, and Annapurna regions you basically know what to expect each day—where the villages are, which lodges to stay in, when and when not to attempt to cross the 5,500 m passes, what food is available, etc. Here, we kind of knew where we were (turns out that Pasang had only gone as far as Tin Pokhari, and didn’t really know the way beyond that). We didn’t see another human being for over two weeks, an experience practically unheard of in today’s Nepal. I spent sleepless, rainy nights worrying about whether we’d be able to cross the high pass the next day if our rain was its snow, making an ascent impossible and delaying or canceling the journey in the face of our finite provisions. We climbed over some of the most rugged, little known, and beautiful terrain I’d ever encountered in over 40 years of remote area fieldwork in the Nepal Himalaya, Peruvian Andes, Russian and Mongolian Altai, and East African Highlands.

Figure 7 (left): The moist Makalu-Barun jungle, which receives over 3,000 mm or precipitation per year; Figure 8 (right) Climbing up the Lamini Danda (photographs by A. Byers).

On day one, we trekked through oven-like temperatures from Heluwa (800 m) to Tamku (1,500 m). The heat made me feel faint and spacey at times, but it was the only time in the entire trek that I was faster than our young porters who, used to living at higher and cooler altitudes, just couldn’t take the heat and humidity. From there it was on to Dobotak, an especially steep ascent and descent where Pasang showed me wild fruits and nuts favored by bears; spoke of the people-wildlife conflicts that still plague the region, especially in the summer when the corn ripens and bad-tempered Himalayan black bears insist that it rightfully belongs to them; and casually mentioned that large, long-haired Yetis live in a region a week’s walk north of us.

I remembered Dobotak well from my work there in the 1990s, especially the time that I visited Pasang’s father, now long deceased, who’d made a point of giving me a precious hardboiled egg. Except for a few blue, corrugated metal roofs that had since replaced the traditional thatch roofs, Dobotak is pretty much the same as it was in the mid-1990s, although the lack of men, now working in Korea or Dubai or Malaysia, was conspicuous. Pasang showed me a large prayer wheel near the village gompa that one of our staff, the late Tashi Lama, had provided to the village on behalf of the Makalu-Barun project. From Khandbari to the last settlement at Saisima, it was touching to see how Tashi, and so many other project staff such as Ang Rita Sherpa, Tsedar Bhutia, and Chirring Lamu Sherpa, were remembered with such fondness.

Then it was on through broadleaf evergreen forests to Gongtala, home of the sacred Khembalung caves that Johan Reinhard had explored and written about in the 1970s. These caves are believed to be the entrances to the “hidden valley” (beyul) of Khembalung, one of a considerable number of hidden valleys in the Himalaya established by the Indian Buddhist yogin Guru Rinpoche in the eighth century A.D. to serve as refuge for Buddhist doctrine and followers of Buddhism in times of war and evil. There are stories of lamas who have visited the Khembalung caves to meditate and who then disappear, presumably because they’d found their way into the beyul and see no reason to return.

The next day we proceeded on to the settlement enclave of Saisima, passing the footprint of Guru Rinpoche left in stone thousands of years ago that I had seen 27 years earlier with Bhakta Ram. While I was descending the slippery stone trail down to the bridge I was thinking about how climbing Kilimanjaro, which I had done for the third time in July, 2017 as a guide/lecturer for National Geographic Adventures, was a piece of cake compared to trekking in the Makalu-Barun, and how the trails here had definitely gotten steeper and infinitely more difficult over the past quarter of a century. Taking my mind off the slippery trail for a split second was all that was needed to send me spinning head over heels and slamming against a large boulder, with a sickening “crunch” sound where it connected with my chest. I remembered thinking as I was falling that “this is it! This is the big one, the fall that’s going to break your leg or your back and confine you to a wheel chair for the rest of your life, you fool!” But at worst it was just a cracked rib, painful as hell, and something that was to plague me for the rest of the trip and for weeks afterwards. Sneezing or coughing were enough to make me nearly pass out. But there was no turning back now, and I was determined to walk across the wilderness.

Figure 9. The settlement enclave of Saisima and the old gompa built with funds from the Makalu-Barun Conservation Project in the 1990s. A new and much larger gompa is currently being built nearby with funding from a Swiss donor, as the 2015 earthquake de-stabilized the hillslope upon which the old gompa sits, raising concerns about a possible landslide (photograph by A. Byers).

Deep Rai, our guide from Himalayan Research Expeditions (http://www.himalayanresearch.com.np/)

had purchased a goat from some shepherds encountered along the way for the staff, but the lamas at the Saisima monastery wouldn’t allow its slaughter on sacred ground. So they took it deep into the forest for the killing and butchering. Grilled goat, sauteed nigro (fiddleheads), and sautéed wild oyster mushrooms made for a particularly fine dinner that night. The forests of Makalu-Barun are loaded with wild edible foods, like bamboo shoots, saag (stinging nettles), sulpher shelf mushrooms, and other delicacies, if you know what to look for.

From Saisima, we climbed for three hours up through leech-infested bamboo-broadleaf evergreen forests to a campsite at Bali Kharka, a short day since the next days’ climb of 1,000 m or more up the Lamini Danda would take between 5 and 7 hours. From Bali Kharka we climbed up from the bamboo-broadleaf forests, mostly in the rain, to the fir/birch/rhododendron forests higher up, then through forests of tree-size rhododendron, then up to the Sutlej campsite now surrounded by shrub-sized rhododendron. The next day was on up to the dwarf rhododendron and shrub juniper of a beautiful alpine campsite at Eklai Pokhari, a single lake as the name implies, overlooking the Apsuwa valley and Chamlang mountain range to the north.

We were now in yartsa gunbu hunting grounds, and Pasang said that every June some 500 collectors come to the region in search of the valuable fungus. We found very little in the way of environmental disturbance or garbage at the yartsa gunbu camp sites, as widely reported for other areas in Nepal and Tibet. In remote regions such as Makalu-Barun with no roads, glass and canned goods are too heavy to pack in and harvesters use local foods—rice, potatoes, dal—instead. And fuelwood is packed in from the tree-size rhododendron forests below, thus sparing the dwarf rhododendron and shrub juniper of the alpine zone that have been devastated elsewhere.

That evening I saw Khanjendzunga glowing like a white diamond in the east from the comfort of my tent, the foothills below turning a beautiful bluish-green as the dusk progressed. The beautiful Chamlang mountains and glaciers to the north would emerge whenever the gods showed pity on us, and graciously opened up the ever-cloudy and drizzily Makalu-Barun skies for a few precious moments.

Figure 10. Sutlej camp, overlooking the Apsuwa river valley. The Chamlang mountain range is due north, to the right of the photo (photograph by A. Byers).

The next day at the Eklai Pokhari camp was particularly cloudy and foggy, with no sign of letting up, and Deep suggested that we take a rest day instead of attempting to find the poorly marked and little used trail under such difficult and unknown conditions.

“Better to be safe than sorry,” he said. “I know. During the 2014 snowstorm in the Annapurna region I kept my trekking group down in Manang instead of trying to cross the Thorong La. But other groups insisted on climbing up to the pass in spite of the snow, and 32 people died.”

Point taken. So I enjoyed a rainy but comfortable rest day, catching up on laundry, writing, and tending to some 30 leech bites collected from below (note: once the itching becomes unbearable, an antihistamine works wonders).

The forests that we passed through are, for the most part, in as pristine condition as one can find in Nepal, aside from a corridor of disturbance for 10 m or so on either side of the trails resulting from the annual livestock migrations to and from the alpine pastures. But the alpine pastures that we were walking through in the park are far from pristine, having been grazed and modified for hundreds of years by Sherpa and Rai yak and sheep herders. Here, slopes that are naturally covered with rhododendron shrub above treeline have been cleared of up to 60 percent of their woody vegetation to promote grass and sedge growth, and the white skeletons of burned shrub juniper and dwarf rhododendron are testimony to a relentless and continuous effort to convert the native alpine vegetation to grassland. The good news, however, is that because the Makalu-Barun regions receives so much rain, alpine ecosystems tend to rapidly heal themselves to a full and continuous cover of grasses and sedges, in spite of hundreds of years of annual disturbances. In drier climates, such as in the Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park to the northwest, the use of shrub juniper for fuel by lodges and trekking groups was turning much of the upper Imja Khola alpine into a high altitude wasteland by the early 2000s, since it takes hundreds of years for alpine juniper to reach even a few centimeters in diameter, and the bare areas left behind encouraged the accelerated erosion of the thin alpine soils. According to Johan Reinhard, even in the 1970s tons of juniper were being cut and burned each climbing season in the Everest base camp as part of the expedition puja ceremony. Both practices were discontinued in 2004 thanks to the actions taken by the Khumbu Alpine Conservation Committee

Figure 11. Guide Pasang Sherpa gazes off into a typically cloudy, drizzly alpine valley (photographs by A. Byers).

(KACC), a local NGO formed by communities concerned about the degradation of their alpine ecosystems and long-term impacts on tourism.

Unlike the more developed trekking regions in Nepal, however, the remote valleys of Makalu-Barun are still home to a number of secrets and mysteries, some of which are difficult to entirely understand.

In the fall of 2010, for example, my son Daniel and I trekked down the entire length of the Hongu valley, from Kongmadingma to Bung, Cheskam, and on to the airstrip at Salleri. We were doing a study of the dangerous glacial lakes in the valley as part of a grant from the National Geographic Society, and knew of only two or three other westerners who had completed the trek during the past 50 years. They included the climber/cartographer Erwin Schneider in 1956, and American adventurer Jack Cox in 1995, both of whom got lost in the dense forests down by the Hongu river channel and who ended up boiling and eating their boots, belts, and leather namlos just to survive. Fortunately, we had a guide who’d been to the Hongu the year before searching for yartsu gunbu, and who kept us on an ancient and long-abandoned trail high up the ridge all the way down to Bung.

One early morning on October 31, 2010, I heard J.B. Rai, our sirdar, and Kamal, his assistant, walking around outside and talking. At breakfast, J.B. was very quiet, and looked like he was worried about something. Then he looked at me and said, “Last night, Kamal was visited by a ghost.”

Kamal said that he awoke around midnight to hear a noise like someone pulling up grass, and occasionally loudly slapping the tent. Sure that the porters were playing a joke on him, he unzipped the tent and jumped outside, but found nothing. Sometime after returning to the tent he heard the same noises, but this time with a sound like a loud, nasal, high pitched ‘neh neh neh’ sound from multiple sources that would begin in front of the tent, then start again behind it, then to the side, then around and around continuously, getting louder and louder until it suddenly stopped.

By this time thoroughly frightened, Kamal dug himself deep into his sleeping bag and stayed there until the morning.

After J.B. told me Kamal’s story, he and Kamal took me to a spot immediately behind their tent to what was in fact the fresh grave of some unfortunate soul, hastily covered by slabs of alpine turf and stones. Arriving late the previous day, Kamal had unknowingly pitched his tent practically on top of the grave site.

We decided not to tell the porters of this for fear of a real or imagined mutiny, and shortly afterwards we departed for the trek down the Hongu valley.

Most westerners that I’ve told the story to stare at me for a moment with one eyebrow raised. Nepali friends, however, see nothing really remarkable about it. This was not an evil spirit, they say, just something that was just trying to tell us that it was still around, most likely confused, and looking for a way to the next world. Another friend said that a violent and quick death, such as from an avalanche or flying rock to the head, could leave a spirit disoriented, since there were no family members in the living world to help it along to the next. Daniel said that he himself had felt as if were being watched ever since we’d arrived, especially late at night when he stepped outside to pee. Other Buddhist friends have since told me that if this ever happens again, chanting “Om mani padme hun” could comfort and help guide the spirit into the next world.

My western brain continues to puzzle this one out, wondering if it was really nothing more than a Himalayan thar grazing around the tent, or Snowcocks with their nasal calls, or a combination of the two. Regardless, it was the best Halloween in years!

From Eklai Pokhari we continued our sojourn through the spectacular alpine, and on to Tin Pokhari, Kalo Pokhari, and up over two more passes to a camp site on a ridge known as Gurung Gang, or “place where the Gurungs gather.” Pasang said that from here one had a choice to head north over a high pass toward Makalu that we could clearly see, or west over another high pass toward the Hongu valley, which was our route.

That night it rained continuously. Sleep was impossible, and I worried, like so many other nights before, that snow would prevent us from crossing the Sahuni La still in front of us, forcing a return and two-week retreat to the lowlands. But the next morning was clear, sunny, and snowless, and the Sahuni La was clear. But after the pass Pasang and I spent hours and hours descending a very steep, rocky, wet, knee-killing 2,000 m down to the Sankhuwa river, from the treeless grass/shrublands of the alpine to the dense forests of big leafed Rhododendron hodgsonii below. If this trail is indeed to be developed into a trekker-friendly route, breaking it up into shorter segments would be highly recommended. The next morning we ascended once again to the alpine zone and to the Sankhwa Sii camp site, perched upon a beautiful ridge overlooking the Sankhwa river below.

And then one day, after dozens of passes had been climbed to, and thousands upon thousands of meters ascended and descended, we stood at the rim of the Hongu valley. Trouble was, nobody knew the way down to the Hongu river, in spite of all the previous assurances. As planned, I sent out three parties of two-man teams the next morning to scout the different route possibilities—north, west, south--and they all came back with the same report.

Nada. Shidyo. No possible way down. The former Game Scout who’d said that he knew of a trail down to the Hongu became remarkably silent. Later, in comparing my GPS-generated track of our trek with the map contained in Johan Reinhard’s 1977 Khembalung article in Kailash, it looked to me like we had both followed an identical route from Saisima to the edge of the Hongu valley here. But Johan thinks that he and Yvon Chouinard were able to make the descent to the Hongu because there was so much snow. Snow would have made it much easier to climb down what were otherwise steep, precipitous, and dangerous hillslopes and rock faces, which is precisely what we faced no matter where we searched. Still, it seemed odd that local people who’ve lived their entire lives in the region couldn’t find a way down.

Regardless, there I was at 5,000 m with eight cold and hungry Rai boys, and my choice is to either retrace our steps for 3 weeks back to the airstrip at Tumlingtar with limited supplies, or charter a helicopter to take us on a four minute flight down to the Hongu valley, and continue the traverse from there.

Not much of a choice. We used the satphone to call Fishtail Air and specifically asked for my friend Tim Field to come pick us up. In May, Tim had flown me and my two colleagues from Dingboche in the Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park over the Amphu Laptsa and West Col passes into the Barun valey in Makalu-Barun National Park. We went to see if we could determine the source and cause of the April 20, 2017 glacial lake outburst flood, and I knew that he was a superb pilot. I returned to the Barun valley by helicopter three weeks later with a porter and research assistant to complete a more detailed, two week-long analysis of the flood and its cause, prior to beginning the long walk back to Khandbari and Tumlingtar. If anyone could land safely on the ping pong table-size “helipad” that had been hastily constructed on the valley rim at Sankhwa Sii, it was Tim.

Figure 12. Tim brings the helicopter onto the ridge above the Hongu valley below (photograph by A. Byers).

Tim and an assistant landed, and several short flights later the whole team was safely at a campsite on the Hongu river below Chamlang North glacial lake, traveling in minutes from the cold, clammy, wet reaches of the eastern Makalu-Barun to the sunny, rain-shadowed, warm alpine pastures of the upper Hongu. The staff were elated by the warmth and familiarity of the Hongu, and so was I.

The next day I climbed up to Chamlang North glacial lake, also known as “464,” one of Nepal’s high risk lakes in terms of a GLOF because of the large masses of overhanging ice perched directly above (see: https://vimeo.com/69665582). In the event of an ice avalanche into the lake, caused by an earthquake, gravity, or warming trends, a surge wave could be created that overtops and breaches the unconsolidated terminal moraine to the far right, unleashing millions of cubic meters of water in the form of a glacial lake outburst flood. Thankfully, I didn’t see much change in the condition of the overhanging ice in the eight years since we’d first visited the lake, most likely due to its high altitude and

Figure 13. Chamlang North glacial lake in 2017, also known as Lake 464 (photograph by A. Byers).

year-round freezing conditions. But at some point in the future, mostly due to continued global warming, a flood from 464 is pretty much inevitable.

From there it was a three-hour trek to Kongmadingma camp, passing the grave site of Kamal’s ghost which by now is hopefully enjoying the afterlife and its new home. The signs and noise of civilization greeted us for the first time in over three weeks—lodges, tents, and countless groups of 20+, 30-something tourists in the latest candy-colored trekking outfits, most attempting to climb Mera Peak. Especially after crossing the Mera glacier and descending to the tourist village of Khare, the groups of returning climbers and trekkers mushroomed. It was clear that tourism had grown significantly during the past few years and, as mentioned previously, now comprised the vast majority of tourists visiting the Makalu-Barun national park. Dozens of young porters, anxious to get back to Lukla and the next job, trotted passed us throughout the day, and the trek was transformed from one of wilderness solitude to one of constantly stepping aside and waiting until they passed.

Figure 14. The remote and beautiful Hongu valley, as seen from the slopes of Mera Peak, looking back over the territory that we’d just crossed. Chamlang (7,319 m) is center-right. Chamlang North (464) and Chamlang South glacial lakes lie immediately below the peak (photograph by A. Byers).

The next day we crossed the Mera glacier and climbed down to a campsite about an hours’ walk below the village of Khare, which was much quieter and peaceful than the tourist and lodge-filled Khare. From the Khare camp we descended to the alpine settlement of Tagnag, site of a major GLOF from the Tama Pokhari in 1998 that destroyed much of the Hinku Khola’s riparian zone and took out bridges for 100 kilometers downstream. This was also the site of one of our Alpine Conservation Partnership (ACP) projects in 2007, which encouraged lodge owners to find alternative sources of fuelwood to the fragile and slow growing shrub juniper that they were burning by the truckload each year, destroying their alpine ecosystems and, in the long run, the source of their livelihoods, in the process. As I walked down the trail I couldn’t help but feel pleased by the valley’s green and visibly undisturbed condition compared to only 11 years ago, and by the fact that the stacks of shrub juniper that I’d seen in 2007 outside of every lodge were now gone, since replaced by solar, kerosene, and propane.

Figure 15. The camp site in the Hongu valley where Kamal met the ghost. The circle shows the cave formed by boulders where we found the grave site (photograph by A. Byers).

Still, the next “alpine challenge,” both here and in every other alpine tourist destination in Nepal, is to figure how to export and recycle the tons of solid waste—glass, plastic, tin cans—generated each year and ultimately ending up in local landfills. Usually referred to as “burnable garbage,” burning such waste releases toxic chemicals into the air, and once buried the waste contaminates local groundwater. Although solid waste management and landfills have been major problems for decades in the Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park, local people recently started an initiative to collect and send the solid waste back to Kathmandu for recycling. This will hopefully prove to be successful, and ultimately replicated by other park’s throughout Nepal.

In Khote, we’re now back in the warm and friendly fir/birch/rhododendron forests. Commanding Rai, a national park friend from our alpine conservation and restoration work in the Hinku valley in 2007, came to my tent to talk and reminisce about old times. Tomorrow it’s a steep climb up to the Jaljala Pass, then another steep, knee-killing descent to Lukla on a new stone staircase built by local people to encourage the recent growth in tourism.

And then we were in Lukla, with its hundreds of tourists, shops, cafes, candy colored roofs, wifi, coffee houses, bakeries, helicopters, STOL aircraft, and noise. After the silence and remoteness of the past several weeks, it was a definite culture shock. After a little thank you speech to the staff, distribution of tips, and dinner of dal-bhat, the hot shower and soft bed felt very good indeed. I slept until noon the next day.

Figure 16. Crossing the Mera glacier (photograph by A. Byers).

Failure Turns to Re-discovery? Needless to say, I was disappointed that we didn’t entirely succeed in crossing the entire Makalu-Barun wilderness area by foot. On the other hand, that’s why they call journeys such as these “adventures,” which by definition are “undertakings where the outcome is uncertain.” And I did learn a number of extremely valuable lessons.

For one, we hadn’t done enough background research to find a local guide or guides who knew the correct path. What we should have done was conduct a pre-expedition trip to Khandbari and the park’s buffer zone to consult with yak herders, shepherds, yartsa gunbu harvesters, local trekking/ mountaineering guides, and others who might know the way.

Second, we could have consulted with trekking map companies, who regularly received information from local people about new prospective trekking routes throughout Nepal, and who might have shed some light on the various routes across Makalu-Barun. Mea culpa. My fault. I still don’t know what I was thinking, but by not doing any of these, I had to evacuate my entire team for a 4 minute helicopter ride down to the Hongu valley below, to avoid a 3-week retreat back through some of the most vertical, rugged terrain I’ve ever been through.

But pundits have been saying for millennia that “it’s not the goal, it’s the journey” that’s important. And in fact, during the course of the trek across Makalu-Barun, I re-discovered one of the most beautiful, remote, rugged, and forgotten trekking areas in Nepal.

After all the challenges of the past 20 years, Makalu-Barun remains one of the best kept secrets of Nepal’s protected areas. The park offers everything from extreme mountaineering to long distance wilderness trekking to shorter treks that are perfect for the serious bird watcher and naturalist. These little-known treks and trails could be improved and mapped with little effort, designed from the beginning with leave no trace and solid waste recycling in mind. Many of the trails can be challenging, yes, especially compared to the Khumbu, Langtang, or Helambu regions. But they’re as close to wilderness as one can get in the Himalayas, and without the crowds, noise, traffic jams, and mule and dzopio trains bottle-necking the suspension bridges while pushing the occasional tourist off the trail. And where else in Nepal can the adventure tourist trek for weeks without seeing another, or very few, human beings, most of the time immersed within thousands of square kilometers of pristine forestland with unparalleled floral and faunal diversity?

Last but not least, the park and buffer zone offer unprecedented opportunities for a nature-based economic development of the Makalu-Barun region. Training for local people in tourism-related skills could result in a range of new jobs and employment opportunities, such as guides, cooks, lodge managers, and naturalists, which in turn could help to increase incomes while decreasing the trends of outmigration. A resurrection of the Makalu-Barun Conservation Project’s cultural conservation programs, promotion and sale of local handcrafts, and capacity building programs could once again help to supplement traditionally mixed local economies and livelihoods in low impact, environmentally friendly ways.

In Tamku, local officials visited our camp one morning and asked how they could develop tourism in the region. My response was that the blueprints for economic development, cultural conservation, and skills training already exist in the form of the original Makalu-Barun Conservation Project’s management plans. These plans were created by some of Nepal’s best minds in the course of years of field work and consultations with local people, including Dr. Tirtha Shrestha (Natural Science Specialist), Dr. Lhakpa Sherpa (Park Management Specialist), Dr. Kamal Banskota (Tourism and Economic Specialist), and Mr. Rohit Nepali (Community Development Specialist). Adjustments would have to be made in light of all the changes that have occurred in the interim, of course, but the basics are still there. And, most of the people who worked on the project in the 1990s are still around, anxious to provide their expertise and advisory services if given the opportunity to do so.

Finally, botanist T.B. Shrestha once described the Makalu-Barun region as containing “the only major natural habitat[s] in Nepal where the vegetation cover from subtropical to alpine may be seen in a single sweep of slope…[it] is Nepal’s last pure ecological seed.” In spite of the impacts of wars, globalization, and changing demographics, Makalu-Barun continues to show exceptional promise of once again becoming a model of nature-based economic development concurrent with long-term conservation. It’s time to once again develop and support the idea of “walking on the wild side” of Nepal’s national parks, and turn the successes of Makalu Barun’s past into the successes of its present and future.

***

Alton C. Byers, Ph.D. is a mountain geographer, conservationist, and mountaineer specializing in applied research, high altitude ecosystems, climate change, glacier hazards, and integrated conservation and development programs. He received his doctorate from the University of Colorado in 1987, focusing on landscape change, soil erosion, and vegetation dynamics in the Sagarmatha National Park. He joined The Mountain Institute (TMI) in 1990 as Environmental Advisor, working as Co-Manager of the Makalu-Barun National Park (Nepal Programs), Founder and Director of Andean Programs, Director of Appalachian Programs, and Director of Science and Exploration. In 2015 he joined the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at the University of Colorado at Boulder as Senior Research Associate and Faculty, and currently works on a range of research, writing, and teaching projects in the Himalayas, Andes, Appalachian, and Rocky Mountains. His work has been recognized by the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal from the Nepali NGO Mountain Legacy; David Brower Award for Conservation from the American Alpine Club; Distinguished Career Award from Association of American Geographers; Ecosystem Stewardship Award from The Nature Conservancy; and Honorary Lifetime Member of the Nepal Geographical Society. In 2016 he was received a Fulbright Specialist award to teach mountain geography at Tribhuvan University, Nepal, and has twice been shortlisted for the Rolex Award for Enterprise. He currently spends between three and six months per year conducting field work in remote mountain regions of the world, dividing the remaining time between writing, hiking, and organic gardening. Dr. Byers has published widely on a range of scientific topics, and is an author and co-editor of Mountain Geography: Human and Physical Dimensions (University of California Press at Berkeley, 2013). His most recent book is titled Khumbu Since 1950, a unique collection of historic photographs of the Mount Everest region that Byers has replicated over the years.

***

Suggested Readings:

Byers, A.C. 1996. Historical and contemporary human disturbance in the upper Barun valley, Makalu-Barun National Park and Conservation Area, east Nepal. Mountain Research and Development 16(3): 235-247.

Byers, A.C. 2017. Eastern Himalayan wilderness lore and trapping methods. Unpublished manuscript.

Byers, A., Byers, E., Thapa, D., and Sharma, B. (forthcoming). Impacts of yartsa gunbu harvesting on alpine ecosystems in the Barun valley, Makalu-Barun National Park, Nepal. Forthcoming in Himalaya: Journal of the Association of Nepal and Himalayan Studies.

Cronin, E.W. Jr. 1979. The Arun: A Natural History of the World’s Deepest Valley. Boston: Houghton.

Klatzel, F. 2001. Natural History Handbook for the Wild Side of Everest: The Eastern Himalaya and Makalu-Barun Area. A consise guide to threes, shrubs, birds and mammals. Kathmandu: The Mountain Institute.

Reinhard, J. 1978. Khembalung: The Hidden Valley. Kailash – A Journal of Himalayan Studies 6(1): 5-35.

Shrestha, T. 1989. Development Ecology of the Arun River Basin. Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

Taylor, D. 2017. Yeti: The Ecology of a Mystery. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.