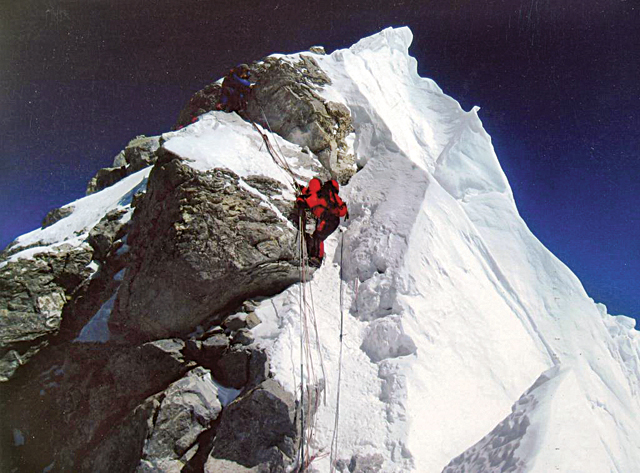

Photo Courtesy: Thamserku Trekking

When Pasang Lhamu Sherpa scaled the summit of Mt. Everest in 1993, it was a triumph for Nepali women. Since then 23 others have reached the top of the world. Who are these women? And why haven’t there been too many like them?

In the spring of 1993, a fierce rivalry was brewing. On one side was Nimi Sherpa who, along with Upasana Malla, formed the Nepali faction of the All Women Indo-Nepalese Everest Expedition team. On the other was Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, leader of the Nepal Women’s Everest Expedition. Both were on a race to be the first Nepali woman to reach the top of Mt. Everest.

Pasang Lhamu, of course, took home the honors. She summited Everest on 22 April 1993. Unfortunately, her descent was plagued with bad weather. She perished on the South Summit and her body was found on 10 May, 18 days later. While Pasang Lhamu never got to celebrate her victory in person, in death, she opened doors and new horizons for Nepali women mountaineers.

The leading light

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa was born in Solukhumbu on 10 December 1961 to a family of mountaineers. She’d been involved in climbing from her teenage years, working as a trekking guide with her father, Phurba Kitar Sherpa. In 1987, she climbed Pisang Peak in the district of Manang. The same year, she also scaled Yala Peak in Langtang and, in 1990, Mt. Blanc in France. She then set her eyes on Everest. Sagarmatha’s summit, regrettably, would prove to be elusive on her first three attempts.

A year after conquering Mt. Blanc, she joined the French Women Everest Expedition with whom she reached a height of 7,997m but was stopped from going further when the team leader cited danger along the route, alongside a lack of oxygen bottles. The following year, she attempted the climb twice, both unsuccessful. An expedition under her own leadership in the pre-monsoon period was thwarted by bad weather after reaching 8,747m. Bad weather, once again, stood in the way in her post-monsoon attempt. This time she had reached the last camp. But if there was one thing these failed attempts proved, it was that Pasang Lhamu had an unshakeable hunger to see her dream through - based on a desire for personal glory as well as to contribute to the upliftment of Nepali women. “I am determined to climb Sagarmatha on behalf of Nepalese women without caring for my life. I am determined to concentrate more on the promotion of national identity on behalf of Nepalese women who are no less courageous than men,” read an official statement that she released shortly before leaving Kathmandu for her final attempt.

A race to the top

In 1990, the celebrated Indian mountaineer and President of the Indian Mountaineering Foundation, Capt. M.S. Kohli, decided to send an all-women team to Everest - the All Women Indian Everest Expedition. After encountering reluctance on the part of both Indian and Nepali authorities, Kohli visited Nepal and met the late Girija Prasad Koirala, the then Prime Minister, who gave the nod to allow two Nepalese women on the team. He also agreed to become the patron of the expedition. The group’s name was thus changed to the All Women Indo-Nepalese Everest Expedition.

Pasang Lhamu was naturally interested in being a part of the team and, along with her husband, had even visited Kohli at the hotel he was staying in. But the matter was not in his hands. “In regard to the selection of two Nepalese ladies, as a normal practice in matters relating to a foreign country, I kept away. I left it to the Nepalese authorities to take their own decision,” writes Kohli in his book, Sherpas: The Himalayan Legends. Instead, the Nepalese Tourism Ministry selected 32-year-old Nimi Sherpa and 28-year-old Upasana Malla to form the Nepali contingent. Nimi had previously climbed Nuptse and Mt. Makalu and came from a rich mountaineering background. Upasana was a professional trekking and mountaineering guide. Pasang Lhamu had been sidelined.

Some reports suggested that Pasang Lhamu had insisted on being the deputy leader of the team, a move that was opposed by Nimi. Kohli, though, claimed to be unaware of such discussions. “Pasang Lhamu or her husband never mentioned to me that she wanted to become the deputy leader of the expedition. It is quite possible that she might have mentioned this to the Ministry of Tourism,” he writes. Rita Gombu Marwah, a member of the All Women Indo-Nepalese Team, maintained that Pasang Lhamu had not been selected because of her rivalry with Nimi Sherpa, who also wanted to be the first Nepali woman to summit Everest.

Disappointed, but still intent on reaching the top, Pasang Lhamu formed the Nepal Women’s Everest Expedition. She persuaded San Miguel Beer to sponsor half of the fees while raising the other half herself. Her two team members were Lhaka Phuti Sherpa and Nanda Rai, along with several Sherpa men, including her husband. On 22 April 1993, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, accompanied by four of the men, scaled Mt. Everest, becoming the first Nepali woman and the twenty first female mountaineer to summit the highest peak in the world. She was 32 years old at the time and the mother of three children. On returning, however, bad weather, which had plagued Pasang Lhamu’s previous Everest attempts, struck again. She was forced to bivouac on the South Summit for the night. Two of the men went down to get help but conditions worsened. Another was sent down the next day but there was no further communication. They had no radios to call for help. According to a Himal Southasian magazine article (dated March 1995), Lhakpa Sonam Sherpa, Pasang Lhamu’s husband, who was not included in the summit group, said the team wasn’t allowed to use walkie talkie sets since they were considered “controlled items” in Nepal. A lack of such a set hindered the rescue attempts, he said.

Pasang Lhamu’s body was found eighteen days later, on 10 May 1993, buried under one meter of snow in the South Summit. Her only companion in the end was Sonam Tsering, whose body was never found. During the time she was missing, however, Pasang Lhamu had propelled to fame. She had been a front-page story in the papers the entire time, and after her body was found, the late King Birendra conferred on her the Nepal Tara, an award that had been given only once before – fittingly--to Tenzing Norgay. She was cremated at Dasrath Stadium, and posthumously honored in various ways. A life-size statue of her was erected in Bouddha and a postage stamp issued in her name. A 117 km road was named the Pasang Lhamu Highway. And aptly, the 7,315 m Jasamba Himal in the Mahalangur Range (where Everest is located) was named Pasang Lhamu Peak.

A storm of controversy

But her ascent, and subsequent death, was fraught with controversy. Rita Gombu Marwah, of the All Women Indo-Nepalese Everest Expedition team, stated that there were two main reasons for Pasang Lhamu’s death. The first was that she attempted the summit too early, considering the weather. Second was her technical handicap; she was known to have difficulty in descending mountains. She supposedly took five hours to get down to the South Summit instead of 45-50 minutes, which was the norm.

A Himal Southasian article by one Marcia Lieberman, published in July 1993, was scathing in its criticism of Pasang Lhamu. Comparing her to Robert Falcon Scott, a British explorer who led his men to their death while on an expedition to the South Pole but was venerated for years due to doctored records, Lieberman accused Pasang Lhamu of similarly risking her team’s safety in her rush to reach the top. “Instead of pluck and determination, we see greed, selfishness, incompetence and reckless disregard for the lives of others. The myth depends upon the suppression of evidence and the distortion of reality and is not healthy for Nepal,” wrote Lieberman, the wife of a member of the American Sagarmatha expedition, who happened to be at the Everest Base Camp when Pasang Lhamu’s story transpired. She accused Pasang Lhamu of not being interested in a team effort, hoping instead to reap all the glory and reward for herself. Lieberman went on to call Pasang Lhamu’s determination “obstinacy,” one driven by ego and self-serving ambition which, tragically, led to the death of Sonam Tsering.

Lieberman further charged Pasang Lhamu of trying to minimize competition even within her own team. Nanda Rai was deemed unfit to summit which left Lhaka Phuti, from her own team, and Nimi Sherpa as her competitors. In an interview with Rajdhani, Lhakpa Phuti acknowledged that in the original plan, all the women from the Nepal Women’s Everest Expedition team were supposed to try to get to the summit together. However, Pasang Lhamu decided to push for the summit early due to her competition with Nimi Sherpa while Lhakpa Phuti was to make her attempt only four days later.

Rumors even hinted that she never reached the summit. Like Mallory and Irvine decades before her, it is probably impossible to know what really happened. But the fact remains that whether she scaled Everest or not, Pasang Lhamu was still a trailblazer: She had the spirit, will power and determination to take up the challenge of the mountain, a conviction that inspired Nepali women who came after her, mountaineers or otherwise.

The dawn of the female mountaineer

Although Sherpas have had a long-standing relationship with the mountains around them, it wasn’t until the arrival of Western mountaineers that they began to venture onto the higher peaks. The noted mountaineer, Alexander Kallas, is considered to be the first person to recognize the natural aptitude of the Sherpa people for high-altitude climbing. Until Nepal opened its borders in 1950, the majority of climbing Sherpas were from Darjeeling, the main Himalayan center for mountaineering expeditions. The first mention of Sherpa women taking to climbing took place in 1959 when Tenzing Norgay’s two daughters - Nima and Pem Pem - and niece Doma joined the International Women’s Expedition to Cho Oyu (8,211m). Nima even managed to reach a height of 6,400m, a record for a teenager then. Their efforts played a substantial role in opening the door to let women become a part of the field of mountaineering in the subcontinent.

Building on that momentum, in 1961, on the recommendation of M.S. Kohli, the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling introduced training courses for women. This proved to be a turning point for women mountaineers as several all-women teams conquered peaks in the years that followed. Some of these teams would feature Indians of Nepali origin but it wasn’t until Pasang Lhamu scaled Mt. Everest that a Nepali woman would be on top of the world.

Following Pasang Lhamu were Lhakpa and Pemba Doma Sherpa who summited in May 2000. Lhakpa, as part of the Millennium Women Expedition, climbed from the South-Eastern route and reached the top on 18 May. The next day, Pemba Doma did the same from the North Col route as part of the Swiss Everest Expedition. Lhakpa climbed Everest again on 23 May 2001, this time from the North Col side, becoming the first Nepali woman to conquer Everest twice and second in the world to have climbed both the north and south sides. For their achievements, Lhakpa and Pemba Doma were awarded the Suprabala Gorkha Dakshina Bahu Award by King Birendra.

A Sherpa dominion

Although Sherpa culture does have fixed gender roles in family and society, women have equal opportunity to make economic and familial decisions. Anthropologists believe that compared to other Nepali cultures, Sherpa women enjoy a relatively higher standing in their society because they base an individual’s status on ability rather than on gender. This is, perhaps, a reason why so many Sherpa women headed for the high peaks after Pasang Lhamu’s ascent. Maya Sherpa, an Everest summiteers, wholeheartedly agrees. “Sherpa culture is very supportive of females, not just in mountaineering but in everything else. The important thing is that one should have the desire to do something worthwhile. No one will stop you then.”

Maya started climbing mountains in 2003, at the age of 23. Her father was a trekking guide and, like Pasang Lhamu before her, she had started out as one too. “It was difficult to get other jobs,” she says. Maya worked as a guide from 2001 to 2003, and seeing how strong and fit she was (she used to be a national level weightlifter), the company she worked for decided to give her a chance at climbing. “I didn’t know much about climbing then but I decided to give it a try.” After a trial period that consisted of 30-day treks, she was sent on a basic mountain training course in 2003. That very year she became the first Nepali woman to conquer Mt. Amadablam (6,812m), the technical peak. In 2004, she went on to climb the avalanche-prone Mt. Pumori (7,145m), and Cho Oyu in Tibet, becoming the first Nepali woman to crown both peaks.

“All of my expeditions were successful, and my confidence grew. When people heard I was a mountaineer, they always asked me whether I had climbed Everest. That was when I decided to try climbing it,” says Maya. So in 2006, she ascended Everest from the south side and a year later, from the north. Then, in 2008, she became the first Nepali to scale Khan Tengri (7,010m) in Kyrgyzstan and, in 2009, the first Nepali woman on Baruntse (7,125m).

Maya then took a break from mountaineering for a few years to focus on family life. She is now back and, in June this year, will be heading towards K2, the second highest mountain in the world and the hardest in the 8000m range. Accompanying her will be fellow Everest summiteers Pasang Lhamu and Dawa Yangzum Sherpa for what has been termed the 1st Nepalese Women K2 Expedition 2014.

Chhurim Sherpa is another well-known female Sherpa mountaineer and a Guinness World Record holder. In May 2011, at the age of 27, she became the first woman to successfully climb Everest twice in a week. After first reaching the summit on May 12, Chhurim followed that feat with another successful ascent on May 19. What made this achievement particularly remarkable was the fact that she had never scaled Everest before.

Eyes on all continents

To date, 23 Nepalese women have reached the summit of Mt. Everest. Of these, 12 have been Sherpas. The rest have belonged to various other ethnicities. A prominent name among them is Moni Mulepati. In May 2005, when Mulepati stepped onto the top of Everest, she became the first non-Sherpa Nepali woman to reach the Roof of the World. She was 24 then. Mulepati, incidentally, wasn’t even aware of this piece of information when I contacted her. “Oh, I didn’t know that! I only knew that I was the first Newari female,” she exclaimed. What made the ascent even more special was the fact that she tied the knot during the ten minutes she was there. Her husband being a Sherpa, it was also intended as a social statement. “The idea came up when we were trying to find out a way to tell my parents and well-wishers about our inter-caste marriage,” she says.

Before 2007, only seven Nepali women had climbed Mt. Everest. This changed with the First Inclusive Women Sagarmatha Expedition 2008 Spring (FIWSE), which consisted of ten Nepali women belonging to different ethnicities. “We were all successful in reaching the top. In a single year, the number went from seven to 17,” says Shailee Basnet, one of the ten. The impression that mountaineering and other adventure sports were beyond the reach of women changed with the expedition. “It opened a lot of doors,” adds Basnet.

Since then, seven members from the expedition have formed the Seven Summits team, of which Basnet is the co-ordinator. Their mission is to climb the highest peaks on each of the seven continents. “Since we trained for only a year before attempting Everest, we realized that if we could climb the peak after just 12 months of training, we had the time, age and energy to dedicate another four or five years to the team,” she says.

Along with her Seven Summits team - Maya Gurung, Pujan Acharya, Pema Diki Sherpa, Nimadoma Sherpa, Chunu Shrestha and Asha Kumari Singh - Basnet has visited 200 schools across the country giving motivational speeches. They also organize weekly hikes around the Kathmandu Valley. “After our Everest climb, we realized that people want to listen to what we have to say, that’s why we started focusing on education, empowerment and environment. Our core mission has been visiting schools, interacting with local women and learning about local environments,” explains Basnet. But the team’s mission goes beyond that, too - it’s also about patriotism. “We’ve actually been to places where people don’t even know about Everest. But once they learn about Nepal, they absolutely fall in love with the place. It’s a reminder that while we have enormous assets in the form of natural resources in this county, we also have the responsibility of letting the world know about them.”

Besides Mt. Everest, the Seven Summits team has so far conquered Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Mt. Koscuiszko in Australia, and Mt. Elbrus in Russia. They are currently on an expedition to climb Mt. Aconcagua in Argentina, the highest mountain in South America. Once they scale all Seven Summits, they’ll be the first Nepali women to do so.

Obstacles aplenty

The fact that there have been only 23 Nepali women on Everest in the many decades since Hillary and Tenzing conquered the mountain is an indicator of the difficulties female mountaineers still face. The reasons, considering the traditional attitudes of Nepali society, are obvious.

“In a typical Nepali family, where girls need permission to even go out, taking up mountaineering is an uphill task. The old-fashioned and biased attitudes of people are a big problem. The conservative belief of men being the bread-winners and women being the bread-makers is a reason why I think the number of female mountaineers is so low,” says Mulepati, who deems herself ‘lucky’ to have had a family who supported all her decisions. And Maya Sherpa, who was born in the village of Patle in Okhaldhunga, admits to being surprised when young Sherpa girls from the city, who aspire to follow in her footsteps, ask her to talk to their parents to let them take up mountaineering. But it’s understandable to an extent, she says. “In the trekking line, one has to stay away from home for months on end, sometimes as the sole female. When I trained for the first time, I was the only female among 60 or 70 men. But my family trusted me, and that was the main thing.”

Of course, there are difficulties besides social norms. “It’s a challenge,” continues Maya. “We cannot compete physically with males and even small problems, such as a lack of bathroom facilities, become big there.” Climbing while menstruating is particularly troublesome, according to her. “Getting from one camp to another is very difficult when we are on our period. But we can’t say anything, we have to go on.”

New horizons

The few women who have been able to successfully summit Everest, say it’s a life-changing experience. For Shailee Basnet, for instance, it opened up a whole new horizon. “I’ve had the opportunity to understand our home planet in a way that so few people in the world can experience. Along with that came seriousness, spirituality, strength and confidence.” Since Basnet considers mountaineering a social platform, she decided to channel the change that mountaineering brought to her life into giving out social messages. For Maya Sherpa, it was about fantasies coming to fruition. “Everyone dreams of traveling the world and making a name for themselves. It all came true for me. I’ve been to more than 20 countries. If I hadn’t taken up mountaineering, I would probably be in my village living a simple life with my kids.” She adds that mountaineering brought her the courage to take on other things and she’s involved with a number of NGOs in the hopes of sharing that courage with others. Maya has also registered an NGO for female mountaineers in order to provide them employment.

“Success on the top has been a great help in my personal life,” says Moni Mulepati. “I have been portrayed to the world as a positive figure ever since and that has led to a lot of respect.” She also feels that the issue of inter-caste marriage has subsided to some extent, if not everywhere, at least in her family.

The 2008 mission showed that there’s a tremendous interest among Nepali women with regards to mountaineering. There were six different ethnicities in the team, not just from the hills and mountains, but also from the Terai. To Shailee Basnet, it proved that it’s not Nepali women who say ‘I can’t.’ “Women across regions, across castes, and all sorts of backgrounds and ethnicity are interested in mountaineering. They’re just waiting for that one push, that one opportunity.”

The 23 are only an indicator of what is to come. Reaching the summit can be daunting but Nepali women are taking small steps to get there. According to Basnet, that’s what mountaineering teaches: that there are no shortcuts.