Rato Machhindranath Rath Jatra, the chariot ride of Red Machhindranath, combines all the elements of a Cecile B. DeMille epic circa 1950: a colorful cast of thousands, towering religious vehicles which could bring ruin to the entire community if they falter or collapse, bands blasting joyous music, enthusiastic throngs dancing in the streets, squeezing into impossible spaces while good-naturedly jostling one another.

As befits Nepal, the prayers of both Hindus and Buddhists accompany the procession. Young and old men all vie for the honor and good luck bestowed upon those who pull the chariot, seizing the four thick ropes attached to the dhama (the long arcing prow representing the Snake God, Nag Karkotak), and tugging for all they are worth. Other life is brought to a standstill. Traffic stops dead in its tracks. Encouraged by the crowds lining the streets, fervent devotees toss buckets of water on the chariot’s path, shout hymns, throw rice and flowers, and light incense and candles as the imposing construction lumbers, spire swaying

As befits Nepal, the prayers of both Hindus and Buddhists accompany the procession. Young and old men all vie for the honor and good luck bestowed upon those who pull the chariot, seizing the four thick ropes attached to the dhama (the long arcing prow representing the Snake God, Nag Karkotak), and tugging for all they are worth. Other life is brought to a standstill. Traffic stops dead in its tracks. Encouraged by the crowds lining the streets, fervent devotees toss buckets of water on the chariot’s path, shout hymns, throw rice and flowers, and light incense and candles as the imposing construction lumbers, spire swaying

dangerously, from one chosen site to another on its way to glory - and the monsoon. For this is the festival of the most beloved and powerful god of the Newaris, Machhindranath, the rain god, without whose benevolence and care, no rice grains would be found in the paddy.

Once every 12 years, the festival is known as Barha Barse Mela, and the chariot is constructed in Bungamati, a charming 16th century Newari village (some say it was settled as early as the 7th century) famous for its woodcarvings, situated about 8 kilometers south of Kathmandu. It is a very fitting location as this is the legendary spot where Rato Machhindranath, also called Bunga Dyo (“God of Bunga”, the preferred name given by the Newari Buddhists and Hindus), was born. It is said that Bhairab came to the site and uttered “Bu” which in Newari means “birthplace”. Then and there, the King of Bhadgaon ordered the town of Bungamati built. Bunga Dyo’s temple, built in the shikara-style (Northern Indian-style temple with tall corncob-like spire), freshly whitewashed and flanked by two lion-like statues (also newly jazzed up in a pinky-purple hue), denotes the center of the village and its very populated, authentic feeling chowk. Directly across from this structure is a giant Tibetan prayer wheel, clearly indicating the syncretic nature of Nepali worship.

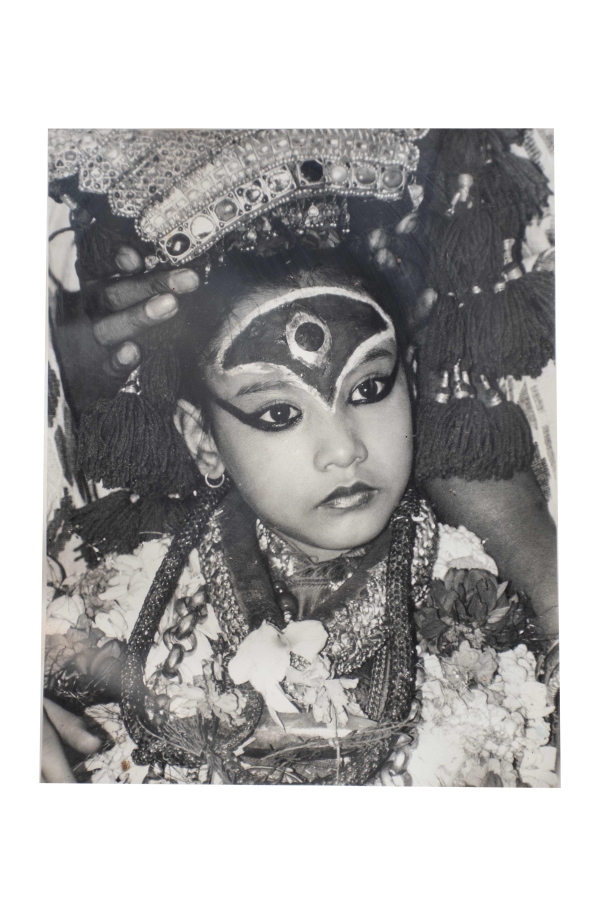

For six months of the year, generally during summer, Bungamati is the dwelling place of this simply carved sandalwood idol. Clearly powerful, this very ancient four-foot, red-faced, many-named, androgynous, wide-eyed god/goddess of agricultural prosperity emanates an almost terrifying sense of atavistic strength. This year is special; the idol in its fantastic chariot will proceed to Jawalakhel and return to Bungamati without wintering in Patan. And most importantly, the Bhote Jatra, the god’s magical jeweled vest, linked to snakes and rainfall, witnessed by the Patan Kuamari (the traditional living goddess), will be held aloft in the chariot by a priest while the crowd roars its approval and swarms the god’s vehicle demanding prasad (consecrated food offerings), while, as witnesses recall, the skies actually do open up.

The only face in the crowd that will be missing is that of the King. It is common knowledge that he cannot go to Buddhanilkanta, the location of the Sleeping Vishnu, because as the incarnation of the living god Vishnu, he is not permitted to see his own image as it is believed he would die if he did so. No explanation has been forthcoming as to why he is not able to visit Bungamati, but the legends connecting various Machhindranath chariot mishaps with the deaths of previous kings could play a role.

THE PREPARATION

A few weeks before the procession, at a suitable lunar moment, the idol is taken from his temple and bathed in holy water, as his devotees exult. This takes place in Lagankhel, Patan, a spot where Machhindra was supposed to have rested on his long journey from Assam. During the Bahra Barse Mela however, this bathing ceremony takes place at Bungamati. The sword of the King of Bhadgaon is included in the ceremonies, and the headman of Kirtipur, whose men will pull the chariot at the end of the festival, is also present.

Ten rituals, including the repainting of the god’s face, are always performed by the same family, the Chitrakars. Those same artisans paint the eyes on the wheels of the god’s vehicle. Then under cover of darkness, he is placed in the throne room of the chariot, waiting to begin his ride.

MORE FISH AND SNAKE STORIES- PLUS A BEE

Machhindranath, Hindu “Lord of the Fish” is also the Buddhist Lokeswar, the compassionate God of Mercy. A suggestion as to how Hindu and Buddhist identities became integrated is as follows: once by the seaside, Parvati fell asleep as Shiva was talking about what he had learned about meditation. The diving guru Lokeswar took the

form of a fish and eavesdropped. Shiva understood that his wife had not been listening to him, but that someone else was. He was furious, and wanted to put a curse on the trespasser. Lokeswar manifested himself in his true form, bringing Shiva to his knees begging forgiveness. Since then the Buddhist deity has also been known as Lord Machhindranath.

Another fish tale concerns a Brahmin woman who gave birth to a son on a dangerously inauspicious day, under such malignant signs that the child was cast into the sea. The boy did not die, but was swallowed by a great fish. Lord Shiva learned about this and saved the child, who was was thereafter known as Machhindra.

Another expert, Mukunda Aryal, professor of Culture at Tribhuvan University, recalls that in oral and traditional history, Vishnu, in the form of an irresistible young dancing girl, so enticed Shiva that he ejaculated, held every drop of semen in his hand and fed it to a fish. This was offered to the Queen of Assam, who subsequently gave birth to Gorakhnath, beloved 7th century guru saint and pupil of Machhindranath.

The sage Goraknath visited Kathmandu valley, didn’t like the reception he got, and therefore caused a drought. He rounded up all nine of the rain-bringing Snake Gods, sat on them, and proceeded to go into a deep meditative trance. People brought Machhindranath from Assam, knowing full well that Gorakhnath would be obliged to stand up in the presence of his teacher. Thus the snakes were liberated, permitting the rains to fall on the parched land and creating Machhindrantha’s reputation as a rain-maker.

Over-riding the protests of his mother, Lord Machhindranath left Assam in the form of a black bee held in a golden ceremonial vessel. To this day the Newaris still avoid killing these insects and priests worship the golden vessel as the God of Rain and Harvest.

GOING THE DISTANCE

Beginning in Bungamati the chariot’s road leads to Chasikot, Bhaisepati, the Nakhu river, Bani Mundar, Ulakhel (where they pull at night in silence, no musical accompaniment allowed), then Pulchowk, Gabahel, Sundhara, Lagankhel, Thati, and finally Jawalakhel. In some locations they stay longer and additional ceremonies and local worship are performed.

Highlights:

-

As the chariot crosses the Nakhu river, snakes of all sizes and colors are supposed to flock around the chariot wheels.

-

In Lagankhel, a priest throws a coconut from the chariot and the man who catches it is assured of having a son.

-

From Lagankhel to Thati - all one hundred meters - some 300 or 400 single women pull the chariot for about half an hour. As Ram Krishna Barahi grinned,”This is the main festival in town for single women.”

LIMITLESS TIME WRITTEN IN THE STARS

The rambling giant has no time limit in its meanderings. The journey can take “anywhere from six weeks to two months or more...” according to Ram Krishna Bahari. “Who knows how many people witness the procession? Maybe, three, four or even five lakhs,” he adds, “and when it will finish depends on the astrologers, the Joshi family, who must calculte the position the stars and moon to assure success.”

WHO FOOTS THE BILL?

The guthi, specific to Newari culture, a group which takes care of its members, generally supply the funds to pay for the event. Although reluctant to speak about money, someone indicated that this year’s cost could be a million and a half rupees.

WHAT HAPPENS TO THE CHARIOT?

The chariot’s parts are not allowed to be destroyed. It is therefore disassembled and the wheels are stored for another trip “if they are still in shape,” laughs Ram Krisna Barahi. And he points out that a few dhama, (the Snake God prow) can be seen lying under the eaves of the sattal at the grass-covered Western Stupa in Patan, surrounded by sleeping dogs and people selling vegetables.

TRAGEDY CAN STRIKE

Even though powered by the devoted eager to serve their imposing deity, things can go wrong. In the past, tragedy has marred the festivities. If the tower falls, it is considered very inauspicious.

In 1680 A.D., according to the historian D. Regmi, Machhindranath lost some paint off his face and the same day King Nipendra Malla died. Furthermore, in 1817, when the paint was again affected, an earthquake followed. Another striking incident: King Visvajit Malla, while attending the chariot festival, thought that the deity had turned its back to him. He was murdered the same day.

When the wheels were mired or the axels broke, bad luck followed. One king was assisting in pulling the chariot and the axels broke 31 times. He died soon after the evil omens occurred. Some may shrug if off and say that accidents have happened and probably inflicted no damage. However, Dr. Rohit Ranjitkar, Nepal Program Director for the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust, remembers that the spire fell into the crowd in the same year, 2000, as the Royal Massacre. So let’s cross our fingers and knock on wood that Rato Machhindranath’s ride fulfills its glorious destiny without any hitches this year.