Lain Singh Bangdel, Art Historian

Photo by Liesl Messerschmidt

Every stone speaks the history of Nepal "~ Kamal Mani Dixit

In the spring of 1961, shortly after moving from Europe to live in Kathmandu, the artist Lain Singh Bangdel was invited for tea by Kamal Mani Dixit, a prominent Nepalese writer-intellectual. Their friendship was the natural outcome of a mutual interest in the arts. After tea, “He took me around to see the sites. It was a revelation,” said Lain. “I saw many things ― wooden temple carvings, sacred shrines, and stone sculpture’”

When asked how old they were, Dixit said, “I don’t know, but every stone speaks the history of Nepal.”

The figurative painter in Bangdel was intrigued and the realist writer in him was moved. What he saw challenged him. He wanted to know more.

“I knew all about modern art,” he said, “but when I wanted to read about Nepalese art there were no books. Nothing of the sort.” After some thought, he resolved to do something about it.

To Lain, the Valley of Kathmandu was “like an enormous open museum where thousands of icons of gods and goddesses in stone, metal, wood, and terracotta were seen scattered around.” Priceless sacred art objects were found in temples and monasteries and in small shrines, under trees, in old palaces and private courtyards, down narrow lanes and gullies, at stone water spouts and fountains, and out in open fields. They were everywhere, it seemed.

He realized that this great trove of ancient art was avidly worshipped by its local devotees, but “virtually unknown to the world.” The sense of discovery thrilled him. Though a few foreign scholars had scratched at the edges, Lain knew that there was a universe of knowledge still waiting to be, quite literally, unearthed; then documented, dated, written about, and ultimately saved from rapacious thieves.

He took up the challenge with passion, and it wasn't long until he was fully immersed in the study, dating, and documentation of hundreds of sculptures and other artifacts. In time, the books he wrote revealed new understanding and appreciation for the artistic heritage dating back over 1,500 years.

1982 - Early Sculptures of Nepal

1982 - Prachina Nepali Murtikalako Aitihas (History of Ancient Nepali Sculpture)

1987 - 2500 Jahre Nepalische Kunst (2500 Years of Nepalese Art)

1989 - Stolen Images of Nepal

1995 - Inventory of Stone Sculptures of the Kathmandu Valley

1996 - A Report on the Study of Iconography of Kathmandu Valley and Their Preservation and Protection

After almost two decades of study, Bangdel’s first major contribution to understanding Nepal’s ancient art history was a large format, 260-page book, entitled The Early Sculptures of Nepal (1982). In it, he examines the range of stylistic details with which the art historian dates imagery. Early Sculptures was a fresh and detailed look at some of the first known statues and other icons found in the Bagmati river basin, Kathmandu Valley. It demonstrates the author’s command of style and form, and his ability to date ancient images accordingly.

In response to critics who faulted for not having an advanced degree in Art History, Bangdel replied: “I am a good art historian because I am an artist. As an artist, I can see subtleties and changes in form the average art historian will miss.” He often caressed the sculptures he studied, to get a 'feel' for the art in them, to understand the subtle stylistic attributes and changes, and to know something of what the artist who created them must have felt.

It was his 1989 book, Stolen Images of Nepal, however, that has had the widest readership and the greatest impact, nationally and globally.

Stolen Images

At first, Bangdel documented where ancient artifacts were found, photographed hundreds of them, and carefully scrutinized their stylistic characteristics so that he could date them. Then, as art thievery was taking its toll, and because Nepal’s ancient artifacts are part of a living legacy, a religious heritage, their identity and safety in situ (their original place) became his goal.

It wasn’t long into his study before he realized that thousands of ancient art objects were being stolen away from the Valley, for sale (undercover) on the world art market. The result was a tragic and growing loss of some of Nepal’s most ancient treasures to insensitive art thieves, unscrupulous dealers, and unsuspecting(?) collectors. It was an illicit but thriving business. In Stolen Images, Bangdel documented the theft of 277 sculptures, a mere fraction of the total.

It wasn’t long until the journalist Kanak Mani Dixit stated the obvious, unambiguously:

‘It is an incontrovertible fact that every ancient stone and bronze statue from the Kathmandu Valley – to the very last one – that now finds itself on an overseas pedestal, is a stolen item... Not one of them was gifted or handed over with the agreement of the faithful.”

In 1969, the shock of what was happening became personal to Bangdel during a tour of museums in America. One evening after visiting the Asian art collection in the Los Angeles County Museum, he was invited to the home of a wealthy collector, a man who had some knowledge of Nepalese art and enjoyed sharing his opinions and showing off his collection. After art talk over drinks, the private connoisseur took him to a special room to view “a recent acquisition.”

What Bangdel saw took his breath away. It was an exquisite sculpture known as an Uma-Maheshvara panel, in grey limestone, 29½ inches tall, of the goddess Parvati with Lord Shiva and their various attendants. Lain instantly recognized it as a one he had photographed a few months earlier in Patan. On its stylistic merit, he had dated it to the 10th century CE (current era). He did not know it was missing. But now, here it was in front of him.

What was once an objet d’réverénce ― cherished by religious devotees for its divinity, was now an objet d’art ― classified, named, and shared by foreign aficionados, far from home. Its exotic provenance, age, and rarity now accounted for its ‘beauty’ and aesthetic value of a far different sort.

Uma-Maheshvara panel, 10th century CE, photographed by Bangdel in situ at Gahiti, Patan. Grey limestone, 29½ inches high. Stolen in the mid-1960s. Held captive by the Denver Museum of Art.

​The Uma-Maheshvara panel from Patan in storage at the Denver Museum. (Museum photograph)

Ted Riccardi has recently described such desecration in general terms (generalized here in both quote and paraphrase):

“Let us take an object―a statue, a piece of stone... It may function as the equivalent of ... [a] good-luck charm. Or, it may be the object of the deepest veneration. No matter... The people who live near it may not know its correct name... It is there; that is all.

“One morning, it is no longer there. It has been taken in the night...”

Wherever it has gone, however far it has traveled, at the other end of the chain of exchange it is gently scrubbed clean of the vermillion powder, and traces of honey and fruit and flower petals that faithful worshippers have gifted it. What disappeared in the dark of night, now sits alone under bright lights thousands of miles and a thousand years, more or less, from its origin. Overnight, says Riccardi, sacred icons like this are no longer objects of religious or superstitious awe but have become works of art, quantified, made to look shiny, and put on view a reflection of what he euphemistically calls “the universal genius of the human race...”

To reverent Nepalese villagers and townspeople, an icon’s age, rarity, and distinguishing characteristics are irrelevant. It is the object’s religious element that has meaning; even a defaced or broken sculpture remains sacrosanct. To international art experts such as Jessica Frazier and Richard David, this suggests an ‘embodied’ approach to art, where the value of an artifact is based on an “aesthetics of presence”; where “the image is ultimately the message.”

Meanwhile, what happened to the Uma-Maheshvara panel between the time Lain photographed it in Patan and the day it was proudly shown to him in California, had become a cultural treasure to his host, but a travesty, plain and simple, to himself.

“Why did he show it to me?” Bangdel wondered, remembering that day at the art collector’s home. “What could I say? What could I do?”

Some years later the panel was donated to the Denver Art Museum. Since it was found in Lain’s book to have been stolen, it has been in museum storage ― “Not currently on view” and not yet repatriated.

You can view ‘Object ID 1980’ online, clean and lustrous at www.denverartmuseum.org/object/1980.231. While there, you can also trace its provenance from 1968, when it was stolen from Patan, to an art dealer in Delhi and on, almost immediately, to a collector in the United States. Twelve years later it arrived at the Denver Museum.

Why are revered art objects of Nepal, stolen from their ancient and emotionally evocative sites? At one level, greed drives thieves and middlemen to make ‘a fast buck’. As one Kathmandu scholar has pointed out:

“Idol theft is a demand-driven trade led by rapacious cultural cannibals. The culprits are not the petty thieves who in any case earn a pittance compared to what the art will fetch under the gavel in New York City.”

A dealer in Nepalese artifacts has put it more frankly ― “I buy from thieves and sell to hypocrites.” The hypocrites are wealthy, private collectors and museums directors with budget enough to pay for coveted artifacts. Once in hand, the purchases are shown off in sterile isolation far from their source, admired primarily for their aesthetic value, devoid of spiritual attachment.

The Price of Publicity

Some people have questioned the wisdom of publishing detailed descriptions of valuable sculptures and identifying their sites around the Valley. Art historians and reputable art dealers agree, however, that publicity is the best protection. Once the description of a stolen art object is published with photographs, and its provenance (origin or source) is established, its value drops and it is no longer saleable on the open market nor can it be legitimately displayed in a reputable museum.

Getting Stolen Images of Nepal published, however, was a major accomplishment and a challenge. On the one hand, it established Bangdel as one of the rare Asian artist-scholars to have identified, classified, and published descriptions and photos of their country’s stolen art. On the other hand, however, when millions of dollars are at stake as they are in this shadowy business, thieves and smugglers, middlemen and collectors, prefer that such a book not be published.

“I got many death threats asking me to drop the project,” Bangdel said. He ignored them.

The high point of the illicit trade in stolen icons from Nepal was the 1980s, though it began as early as the 1950s after Nepal opened to the world, and it still continues off-and-on to this day.

When such art is identified as stolen, museum directors and private collectors ― the self-styled new ‘owners’ of old art ― are obligated to return it to its place of origin. Since the publication of Bangdel’s book, many artifacts have been returned to Nepal (but nowhere near the number stolen). It took ten years from the book’s publication for the first looted artifacts to come home.

The first few were restituted by a private collector in 1999 after he was shown them listed in Stolen Images. They were three sculptures from Kathmandu, Patan, and Panauti and one disembodied fragment from Pharping. The latter was the crudely severed head of an impressive sculpture of Saraswati, goddess of knowledge, music, art, wisdom, and nature.

In 1985, an Uma-Maheshvara image was purchased on the art market by the Museum für Indische Kunst (for Indian Art) in Berlin, Germany. After it was seen pictured in Bangdel’s book and documented as stolen in 1982 from Wa Tol, in Dhulikhel, the Berlin museum director thoughtfully and rightfully returned it to Nepal.

Saraswati, in situ at Pharping prior to its theft in the 1980s. Photos by Lain Singh Bangdel, in his book Stolen Images of Nepal -- Saraswati: pp.279-280.

Numerous other artifacts followed it home. In 2018, for example, two magnificent sculptures acquired by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art from private collectors were returned after a 30-year lapse. One was another Uma-Maheshwar panel originally from Tangalhiti, Patan. The other was a beautiful Standing Buddha from Yatkha Tol, Syambhunath.

Some art objects have been returned to their original site, but most placed for display in the National Museum of Nepal at Chauni, or in the Patan Museum inside the impressively restored Patan Durbar, the former palace of the Malla Kings who ruled the Kathmandu Valley from the 12th to the 18th century CE.

At the Conclusion of Stolen Images of Nepal, Bangdel wrote that “All the stolen images published in this book are religious objects,” pointing out that:

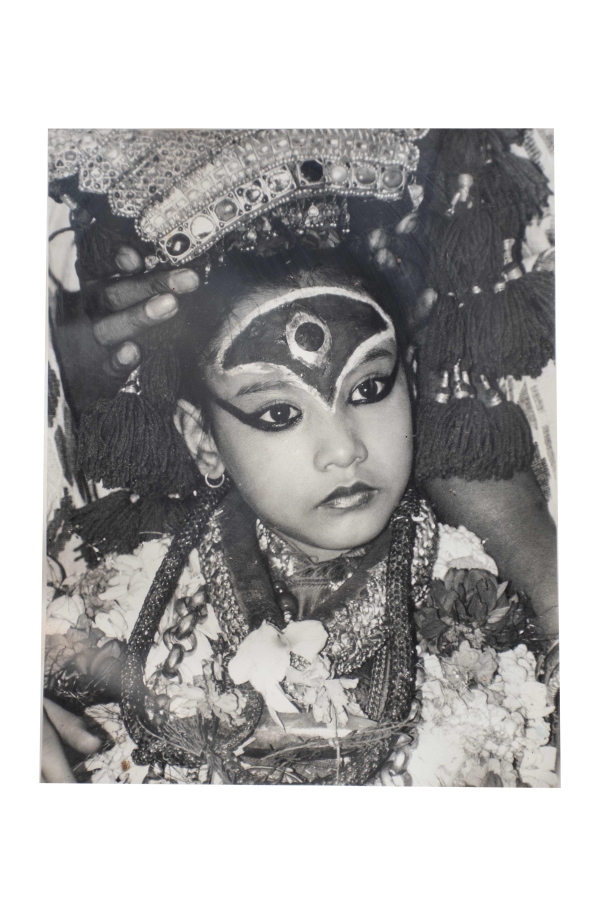

“For generations and centuries they have been worshipped and venerated by the people of Nepal. For them, the sacred icons are live symbols of faith and devotion. The devotees offer them flower, vermillion, honey, milk, butter, grains, sweets and water as though they were alive and not mere pieces of art to be admired. They go to their gods and goddesses both in happiness and sorrow to offer prayers. They celebrate and worship their deities on different occasions with great pomp and festivity.

“When the devotees and people of the country are deprived of their gods and goddesses their hearts bleed. The stealing of such religious images is an atrocity, a serious crime which the civilized world should take steps to stop. Let us hope that someday these stolen sculptures will be returned to their respective temples and shrines.”

Bangdel’s books on Nepalese art history are considered among his most important overall contributions to the art of Nepal. They describe the nation’s ancient treasures in great detail so that others may appreciate their religious and historical significance. In Stolen Images of Nepal, he goes beyond mere documentation to reveal almost three hundred icons, precious from the local worshippers’ point of view and attractive to foreign collectors, out of thousands that thieves have pillaged. Lain Singh Bangdel’s role in documenting many and saving some of them is one of his grandest legacies as an artist.

Standing Buddha, stolen from Yatkha Tol, Syambhunath, in 1986

Standing Buddha,11th-12th century CE Grey Limestone. Approx. height: 35 inches Stolen in 1986. Returned to Nepal in 2018.

Description (adapted from Stolen Images of Nepal, pp. 39, 202)

This masterpiece features a calm, serene expression combined with the gentle, delicate modeling characteristic of Buddha images. The Buddha’s left hand is holding the end of his diaphanous robe while the right hand is extended in the gesture of munificence. Bangdel determined that the overall style is reminiscent of the Mathura school of north India, the oval halo with pearl and flame motif is in Nepal’s Licchavi tradition of (5th-8th century CE), and the flame border around the entire image reflects post-Licchavi period influence. He estimated that this statue was carved in the 11th-12th century CE during the late Thakuri period of rule.

This nearly 1000-year-old statue was stolen from Yatkha Tol at Syambhunath in 1986. In 2015 it was donated by a private collector to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. After it was found to be listed in Bangdel’s Stolen Images of Nepal, the Museum negotiated with the Consul General of Nepal to coordinate its safe return to Nepal. It arrived in Kathmandu in April 2018.