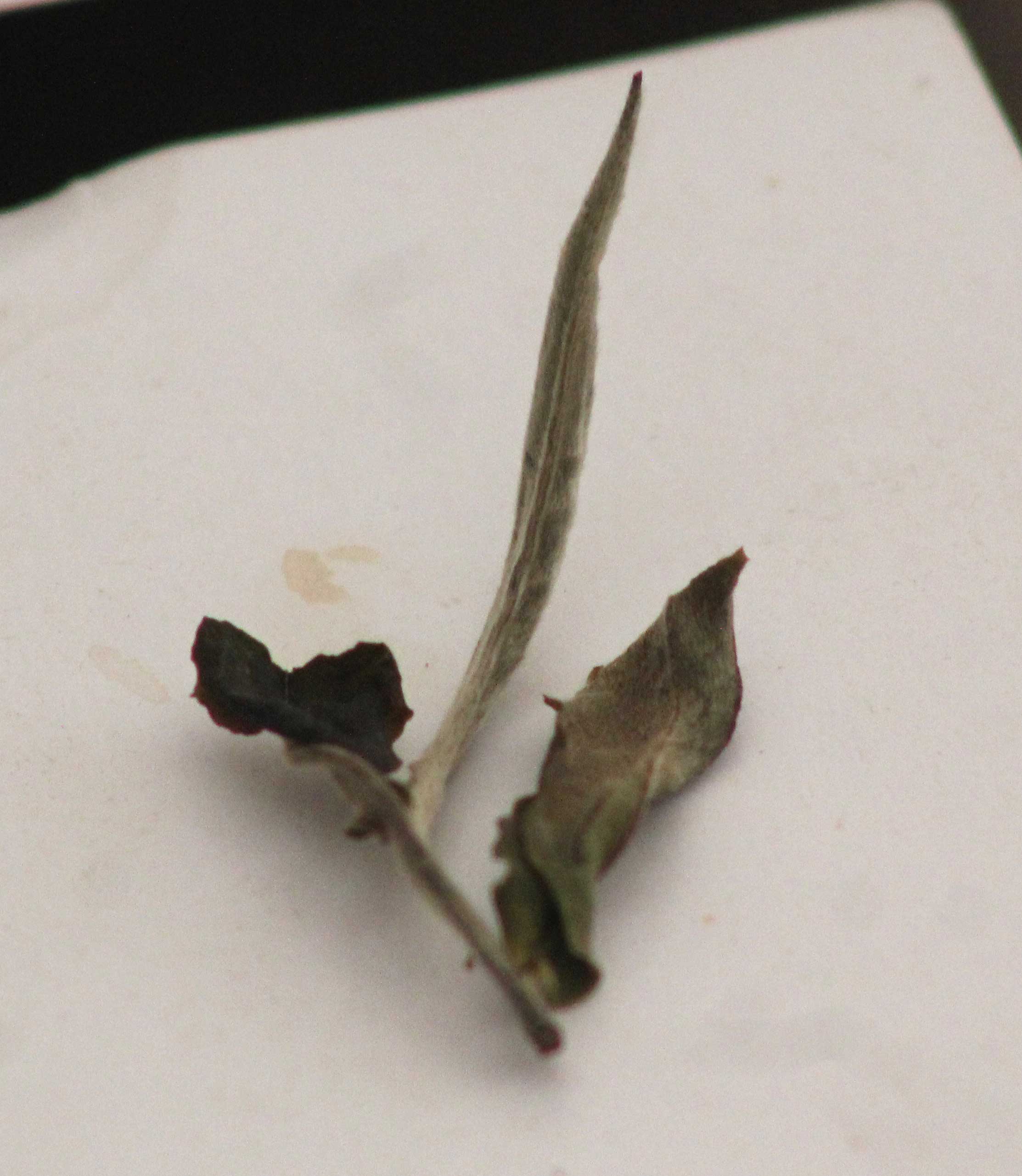

My pre-Khaptad "advice" was a fusillade of warnings. "Watch out for that. The trail is desolate." Then, an aberration, "Khaptad is so beautiful, I've always wanted to go there." And, eventually, the return of the pessimist with harrowing facts: "A few years ago some people were killed enroute to Khaptad. This time of year the poisonous flowers of Khaptad are in bloom. Some years ago, someone touched the plants and died."

I was dying a slow death listening to stories of Khaptad in Mahendranagar, my home town, where I had come for my brother's wedding. As the festivities waned, my longing to see Khaptad heightened. Most importantly, the roads were open. Word had spread that I was going to Khaptad and people began asking me when I would leave. That depended on the fulfillment of my brother's condition: I had to have a companion.

My best friend Harendra, known more affectionately as Haru, volunteered to come along. He is a great friend. Sadly, the same cannot be said about his qualities as a trekker. For a smoke he goes to a shop some 200 m from his house, on a motorbike. Khaptad is a day's walk, if you can really walk. That probably calculates out to one billion 'bike rides for a smoke' from Mahendranagar, on foot.

Two Friends, Two Wheels, And A Town That Was

The first leg of our trip was on a motorcycle. We rode 200 km north from Attariya, a roadside settlement on the East-West Highway in Kailali District. That got us to Silgadi, a town on a hill and, one on the decline. The only thing that rises here is the main street. A thriving trading town during the Rana rule, it is now an unusually quiet town of close-knit buildings, most of them shops. A road from the Terai established Silgadi as a regional market, and ironically, it was roads that ended its prosperous reign. The town's business waned as roads reached Bajura, Bajhang and Accham. "Silgadi hardly produces anything. Everything comes from somewhere else", lamented our solicitous host, completing the circle from the glorious past to the lowly present.

We had difficulty finding dinner on the evening of our arrival in Silgadi. We finally found it, and much more. Hors-d'oeuvre was Khaptad, garnished in folklore. The hotelier began with the tale of a shepherd who had discovered gold on his sickle. The boy had playfully run his sickle over some plants during the day. "Don't touch plants there," he warned, fearing we would try to find some gold of our own. He told us poisonous plants were everywhere, the mere fragrance of which is believed to make travelers sick. The remedy for such a sickness: sucking on lemons and chewing green chilies. "If you're sick and you bite into a chili, it'll taste sweet," he said.

Our local contact, Shivaraj, arranged for us to be accompanied by a game scout as fsar as Jhigrana, the last village before Khaptad. In the morning, we visited the Shailoshwari Temple. Shivaraj appeared as I was tying a neja (a coarse, thin cloth used as a religious offering) around a wooden block. On reaching the game scout's house we learned that he had already left. "He has kids with him. That will slow him down," Shivaraj reasoned, assuring us that the game scout was catchable.

Nearing the end of the first climb out of Silgadi, we saw two soldiers sitting under a small tree. Beside them was an earthenware jar. The only sight more beatific than that of the soldiers serving water to weary travelers is of a farmer's wife bringing food to her toiling spouse. One of them handed us glassfuls of water from the jar.

He also gave Haru hope. It was a level trail ahead for some time he told us. Haru found a new bounce in his steps as we began a shaded trail. I knew it wouldn't last.

After sometime we caught up with our elusive guide and his two children. Dhurva, our guide, decided to rest on the porch of an uninhabited house. A tree, sanctified by rusty tridents, provided the shade. "This is where the Maoists ambushed an army patrol during the Emergency," Dhurva said as we settled down on the wooden benches. There hadn't been any casualties, however, and the area was quiet now, as if to forget the incident. Strangely, violence has a knack of happening in the most peaceful of places.

A Taste of Rural Nepal

The heat soared and reddened the face of Dhurva's daughter. When Haru would ask how far Baghlekh was, his face was a picture of fatigue and hunger. Lunch was in Baghlekh. Rest, too. Until then we walked - through small climbs and short lengths of flat trail, occasionally crossed by a stream on its downhill course. "Lunch will be good," I thought.

It was good, with an 'if' clause. If you had been in a boarding school, where everything on the table passes as delicacy, then it was good. The children were in a boarding school. I had been in one. My taste buds have learned to compromise long ago. Haru's haven't. The woman who cooked our lunch must have been used to cooking for travelers, who never are connoisseurs. The salt in the food was equivalent to the amount of love put in by a mother into a dish. Paying for the lunch felt like buying salt.

"That is our higher secondary school," Dhurva said, pointing to a shimmering tin-roof in the distance. From there, Jhigrana was "not so far."

We stopped in front of a house a few meters before the school building. Three children were sitting on the roof. At Dhurva's request, a girl of around ten brought us a jar of water. Then she went and stood in the doorway. When I got out my camera to take a picture of her I was amazed by how much of a woman she looked already. Everything about her longed for care: her dust-darkened face, her sun-burnt hair, her grimy dress, her bare feet. Care was unlikely to come to any of these. A woman, it seems, must deprive herself of herself. Her expression did not change, not even when I began taking pictures of her. No joy in the eyes, not even a glance towards the camera. Her un-childlike austerity of expression seemed to say that she had already resigned herself to the life of a village female: to child-bearing and child-rearing, to looking after the cattle, and to standing in the doorway, lost in a reverie. It was a scene which had shades of both the past and the future. She was at home looking after her siblings while her parents were out somewhere. Witnessing such instances of precocious maturity, sometimes makes a trek seem extravagant.

Dhurva had stopped to ask if they had yoghurt. They didn't.

As we walked on, Haru and I were learning just how far "not so far" is.

Meeting The Men Behind The Uniform

Two horsemen appeared where the trail turned into a stairway of stones. Dhurva quickly greeted one of the riders with a namaste. Then, he introduced us to the warden of the Khaptad National Park, who was on his way to buy yoghurt. He was on a horse to cover a 30 minute walk. Even the Mongols wouldn't think of that. He had to turn back when Dhurva told him there wasn't any yoghurt available. His horse gave the warden a lesson in modesty. It refused to move unless the other horse led.

Once in Jhigrana, Dhurva took us straight to his house, which also served as a hotel. We were resting on a cot outside the house, when a man in a green jacket, holding a walkie-talkie, descended from a small hill, passing bantering remarks to everyone he met on the way. Shortly, we shook hands with that man, Lieutenant Kul Bahadur Poudel, whose personality, like his hands, emanated warmth. The army post at Jhigrana was under his command, and he took us in.

The lieutenant welcomed us to the post with a round of coffee, a scarce item, prepared only for special guests. In the barracks everyone referred to us as "guests". The lieutenant had a way of making every guest feel special.

Army hospitality, like their profession, is altruistic. The lieutenant oversaw every arrangement to ensure a comfortable night for us. Then he went uphill, to sleep in a bunker dug into the earth.

The next morning we joined a porter bound for Khaptad. As the porter waited for someone, I read the board listing the activities prohibited inside the national park. The last point, which seemed to have been written later than the others, prohibited the killing of animals. The lieutenant had warned us against bears. They were drawn to young bamboo shoots, an entire forest of which grew in one part of the trail. Unfortunately for us, there were no boards in the park telling animals to keep away from humans.

Finding A Swift Friend, Losing The Trail

Jhigrana to Khaptad is climb after climb, one steeper than the other, of stone-and-mud trail winding around gnarled trees. The three of us were resting in a shady part of the trail when a boy appeared. He had left Silgadi at eight in the morning, just two-and-a-half hours before we started from Jhigrana! And his destination wasn't Khaptad, however, but his home in a village of Bajhang District, a few hours further along. The porter, seeing that we had found a new and swifter guide, told us to go on.

We had been told about an old hotel, located at Beechpani (literally 'mid-way water'), the mid-point between Jhigrana and Khaptad. The name seemed apt until we learned that there wasn't any drinkable water in Beechpani. In fact, water is scarce on the trail to Khaptad.

Meanwhile, the hotel's wooden plank beds, stump-and-plank benches, and goth (stable), were all in a surprisingly good state for that of a deserted place. The hotel, it seemed, had preserved itself to entice travelers. Its warmth and life seemed to have been taken along by its former owner.

Our swift friend suggested we should get going, but because Haru had gone off to answer nature's call (the longer one), I asked him to go on and that we would catch up. We never did.

At the edge of the first boggy meadow, we stopped to read the inscriptions on the wall of a house. Etched on a marble tablet were the names of four army men, victims of eleven feet of snowfall a few years ago. The house was built in their memory, to shelter travelers.

Things got worse just as the scenery got better. We walked down into an area of hillocks, the kind seen on postcards of Khaptad, and lost the trail. The place was a maze of trails, many of which ran for awhile before ending abruptly in front of ramshackle huts built in the summer by shepherds. We climbed the highest hill for a better view. There were too many trails to choose from. It was too late and too cold to wait for the porter; we had to start moving again. I saw a small bridge over a stream and decided to take that trail.

We had taken a damp trail along the stream. Haru spotted some boot marks, which, he reasoned were of the army men we had met on the way. We followed the marks. A little later we were facing the Triveni Temple, with the stream forking along two sides of its triangular base. Ten minutes ahead, around the corner of a hill, I saw a blue roof. As we rounded the corner, we saw the triangular flag fluttering in front of the army barracks.

Swollen clouds accompanied the abrupt onset of darkness. Sitting on a bench outside the Khaptad National Park Headquarters building, I eyed the path on which we had entered Khaptad. In the darkening distance I discerned a plodding figure. It was the porter. The gap between him and us had been a mere 30 minutes!

Inside Khaptad's Social Hub

Haru asked the people in the park headquarters office if there was a hotel around. There was; a long stone house with thatched roofing. We headed there.

We had to stoop a little to enter the hotel. Inside, we each became a knight; no matter your name, in that place all men are called 'sir'. Here, to be called 'sir' you didn't have to invent something, win a war, write a masterpiece or be a male school teacher. We had only to have a conversation.

Half-logs were fed to the clay hearth, whose hunger for wood helped speed the preparation of the meal that would satisfy the hunger of the people in the soot-covered room. When talk relented, the gurgle of flowing water was audible. The water and its musical sound flowed incessantly from a pipe in a corner. It was all about sounds and smells: the metallic sound of the radio, acrid smoke rising from the crackling fire to mingle with the aroma of food. When in Khaptad I recommend the Khaptad Hotel, the only one there is.

In the morning, I was taken to the Khaptad Daha, a small lake, by a kid from the second grade. On our way back he traced leopard paw marks on the snow with the audacity of a veteran hunter. A casual walk for him was like being in a wildlife documentary for me. His favorite hangout, however, wasn't the woods. He liked spending most of his time in the barracks.

Later that day, a group of men left for Silgadi. Before leaving, one of them came into the hotel and bought a few bottles of whiskey. "I am going to give one to him now and one when we're in Beechpani," he informed the hotelier. 'Him' was his horse. Alcohol, the hotelier explained, invigorated the horses.

After lunch two soldiers walked us to Nagdhunga (serpent rock), a peculiar large rock formation, having convoluted protrusions running across the face. It began to snow as we reached the site where Lord Shiva is believed to have hidden the snakes from their mythical predator, Garuda.

Leaving the ancient snakes in hiding, we headed for the hermitage of the legendary Khaptad Baba, who, some believe, was aged in excess of 100 years and 50 of which was spent in solitude in Khaptad. There, resting on a low table, a statuette of the hermit gazes in the direction of the helipad where, formerly, distinguished devotees and supplies landed every week. His devotees ranged from the King of Nepal to village peasants. The most distinguished of all was, perhaps, a leopard. According to folklore, the baba could summon a leopard, as meek in demeanor as some of the sheep in the pastures.

Raw Material For The Fulfillment Of Old Desires

That evening we called upon the young army major, a punctilious man who, "never drank more than one peg of whiskey at a time." He asked us to stay for dinner. Through the edge of the window panes behind him I could see snowflakes fall in a slow oscillating manner. The major lived up to his 'one-peg man' reputation. Haru never counts his pegs, and I can never decide when it's enough.

Stepping out from the major's warm room later we saw what you sometimes see when returning to your seat in a theater after a visit to the bathroom - a new scene. Scene I, Khaptad: Outside the waiting room. A moonlit night, snow falling gently. Enter Haru, the major, a captain, and Kapil, with hands in their pockets. Major: "The snow will be gone in the morning." Captain: "Yes." Haru: "Its cold." Kapil (aside): "I hope it remains." Exit Haru and Kapil.

That night was colder than the previous one. In the morning when I pushed aside the curtains, I saw why. Scene II: More snow had fallen while we were asleep. The morning was white. Ice-cold hostilities renewed in front of the barracks; Haru and I pelted each other with snow balls.

On the way to the hotel Haru asked me if I knew which brand of whiskey we had drunk last night. I named a respectable one. He told me it was the one the horses had been given the other day.

The snow made it impossible for us to go anywhere. That day was perfect for me to do what I have wanted to do for a long time: make a snowman. How bad have I wanted it? For eight years I went to a boarding school in a hill station, where it snowed every winter. Only, to my everlasting disappointment, that snow always fell when I was back home on holiday. So, I never got the chance til now.

I lured Haru into joining me by making the process seem as enjoyable as Tom Sawyer made white washing a fence. I succeeded. It was like so many things Haru and I have done together, fraught with bickering, like sharpening a knife; the friction being an essential part. Both of us in our early 20s, working with snow, but arguing just as we used to as kids over issues such as who would bat first in a game of cricket, who'd get to shoot the bird with the catapult, who'd pull the bicycle with the other sitting behind, and for how long. We were kids again. He kicked me soft snow, I shaped it into a pillar-like structure. Haru gave the snowman hands, a feature he kept extolling as the best part of the sculpture. We took pictures while the clouds protected our masterpiece from the sun.

When the sun eventually appeared, the hands were the first part of the snowman to fall off.

Haru began whining about leaving that very day. With the snow there was only one place to go - back to Jhigrana. I gave in, with a condition: We would have to make it all the way to Silgadi.

We did, in just six hours! A trekkers' record, I believe. I wonder how. Could it have been the whiskey?

Massage Away your Stress

A Five Thousand-Year-old Ayurvedic massage helps you de-stress from your hectic life. Life brings in a lot...