Writing on Buddha’s Birthplace

An Emperor’s edict, regal graffiti & more

Lumbini is one of these dreamlike, emblematic places.Sacred trees, beautiful flowers, celestial splendor, eternal tranquility?these are the elements that constitute the place where Siddhartha, the Lord Buddha, was born. A modest grove in the Indus-Ganga Plain became the Sacred Garden of Lumbini.

(Axel Plathe, UNESCO Representative to Nepal, 2013)

In these days of fast online publishing, the Internet, and print publications available on a massive scale, anyone interested in the discovery and significance of Buddha’s birthplace at Lumbini Garden in Nepal’s Terai has plenty to choose from. For nearly 2.5 millennia, however, writings on Lumbini were few and far between. Some appeared literally “on” the site, inscribed directly on a stone pillar dating to the 3rd century BC. Other accounts were written in Chinese travelers’ journals centuries later. Recently, new information has appeared in scientific journals, books and websites.

Here are some highlights:

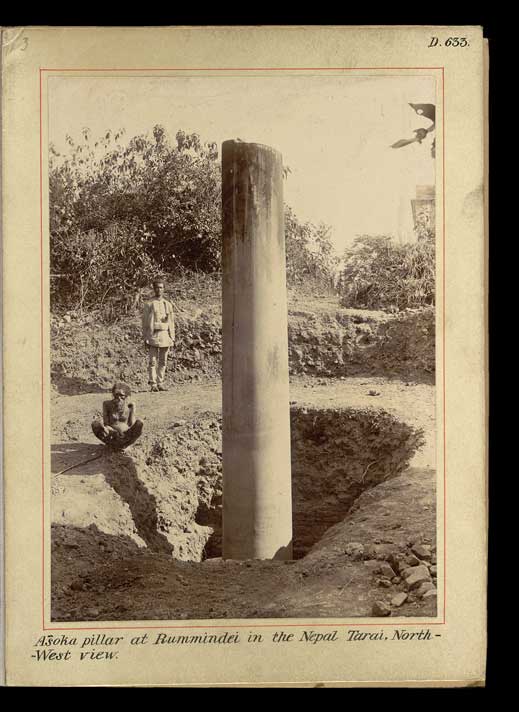

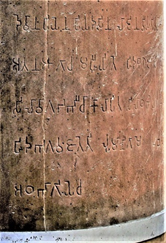

Around 249 BC, India’s Mauryan Emperor Asoka erected a 9.5-meter-high sandstone pillar at Lumbini with a brief inscription declaring: hida budhe jate sakyamuni: “here the Buddha was born, the sage of the Sakya.” It’s in ancient Brahmi script on the second line of the short edict, near the base.

Before it was translated at the end of 19th century, one British observer dismissed such inscriptions as “mediaeval scribblings,” to his everlasting chagrin once their importance was recognized.

Between the 4th and 8th centuries AD, several Chinese travelers visited Lumbini. Two of their journals have survived, with observations that eventually helped archaeologists rediscover the Lumbini Garden and other sacred sites. Faxian (Fa Hien) came in 403 AD. Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang), who followed him two centuries later, described Asoka’s pillar as having been been split nearly in two by “a dragon” (lightning). By then, it was also missing its top-most capital.

They came in search of holy places associated with Siddhartha’s life, including Lumbini (his birthplace), Bodh Gaya (where he gained enlightenment and became the Buddha), Sarnath (where he gave his first sermon), and Kusinagara (the “mahaparanirvana,” where he entered Nirvana upon passing away). They also visited Kapilavastu, Siddhartha’s boyhood home, ruled by King Suddhodana, his father. It was there that Siddhartha first witnessed human suffering (illness, old age and death), which put him on the path to enlightenment.

In 1312 AD, King Ripu Malla of Karnali in western Nepal left a brief inscription in Nepali (Devanagri script) near the top of Asoka’s pillar, attesting to his visit. The top may have been all that Ripu Malla saw of the pillar, much as it appeared sticking out of the ground when rediscovered nearly six centuries later. Malla’s inscription was the last known written testimony left at Lumbini by early visitors. Already, the sacred site had been abandoned and was fast disappearing under dense jungle growth.

In 1896 AD, the pillar was rediscovered by Gen. Khadga Shamsher Rana, the Governor of Western Nepal. After clearing the jungle around it, he dug the pillar out of the ground, saw the inscription near the base, and knew that it was important. To have it deciphered, Khadga invited Dr Anton Führer, a German archaeologist working nearby in India, to come see it. Führer sent a rubbing of it off to his patron, Prof Johann Georg Bühler, a German linguist, who confirmed its historic significance as an Asokan edict.

What happened next is told in Charles Allen’s book, The Buddha and Dr Führer: An Archaeological Scandal. The “scandal” came to light after Führer brazenly claimed in a publication that he himself had discovered the pillar, ignoring Gen. Khadga’s role. When his superiors discovered his deceit, the arrogant Dr Führer was summarily dismissed, and when Professor Bühler in Germany heard of it, he was so shamed by Führer’s behavior that he committed suicide.

During the 20th century, further excavations were carried out, the Lumbini Garden was restored and enhanced as we know it today and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site. Thousands of the world’s Buddhists now visit the once lost sacred site annually. The broken pillar was repaired, and is now one of the Garden’s central attractions where it stands 6.5 meters high behind a small fence.

In 2013, important new archaeological discoveries at Lumbini were published, establishing the great antiquity of the sacred site. Digging deep under the modern building that enshrines the original Maya Devi temple venerating Siddhartha’s mother, archaeologists Robin Coningham, Krishna Prasad Acharya, and team found clear evidence of the original shrine to the Buddha, and dated it to the 6th century BC. Shortly before his passing at Kusinagara (Kushinagar, 95 km SE of Lumbini in Uttar Pradesh), the 80-year old Buddha recommended enshrining the site of his nativity. That appears to have happened. The discovery of the earliest shrine surely ranks alongside Gen. Khadga unearthing the Asokan pillar slightly over a century earlier.

Sources on Lumbini, in addition to those mentioned above, include Kai Weise’s book, The Sacred Garden of Lumbini (UNESCO, 2013), and a synopsis of the recent findings at sciencedaily.com (Nov. 15 1013) entitled ‘Archaeological discoveries confirm early date of Buddha’s life’ based on R. Coningham and K.P. Acharya, et al., ‘The earliest Buddhist shrine: excavating the birthplace of the Buddha, Lumbini (Nepal),’ in the journal Antiquity v.87, no.338 (Dec. 1, 2013), downloadable from http://dro.dur.ac.uk/11508/.