Watering holes, watered-down nectar and wonderful memories.

It is not easy for me to talk about alcohol without sounding like a drunk. I wouldn’t trust anyone who can’t enjoy a drink or two when the day is just right. Such straight-laced people, I think, lack moral vitality: they’re likely sitting on a stick of shame and concealed mortification. The old man who sups dry his dabaka and giggles – I’ll trust him with my life. I like quarelling with a lover with wine-stained lips. I like the patient wait for the first sip of raksi or aila after a puja or sacrifice. I like those men and women of refinement who, when they spill a little of the finest paanch-paani on the table, dab their fingers into the raksi and touch their earlobes with it.

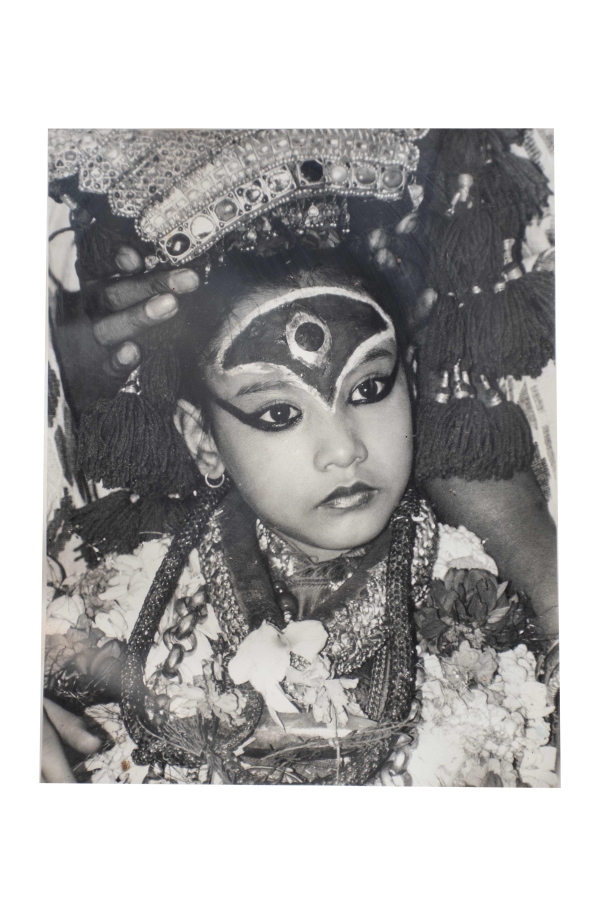

Glucose gets digested into ethanol, and we get drunk. It opens doors to other worlds, and therefore it becomes an essential part of cultures. Sometimes, just the etymological vestige remains in a culture’s language, long after it has given up on the elixit – the Somaras, for instance, recalling a very old hallucinogen in the scriptures. Sometimes, it is such a vital part of the culture that in the very first verses of a scripture, a mother-goddess has invented beer-making yeast to serve her favorites, the humans, like in the Mumdhum. Somewhere it is profane, and somewhere it is the very essence of purity. In Hinduism, invented sometime only in the past five or six hundred years, there is nothing worse than alcohol. In the tantrik traditions of the Kathmandu valley, Madya is central to the means of communication with the gods.

But, drinking is also a very personal experience – with some luck, you’ll be able to spend quite a bit of your life accumulating memories of elation and comradery, of arguments, jealousies, acts of extreme foolishness. With some luck you’ll make mistakes and indescretions that will shame you. With some luck you’ll understand that the dull reality of everyday is a mask over another world of colors and lust and strength that alcohol unlocks for you.

Let me to share a few memories of drinking in Nepal.

A dozen men ran out, laughing and hollering, turning to face the tea-shop from where angry shouts came: screams muffled by distance and burlap, trapped and desperate like the Minotaur in his maze. These were sounds made by a man who suddenly finds himself blind and bound. I was a very young child, still incapable of matching a sign to its significance, so the story floated a few feet above my head and reached other adults who came there, drawn by the hullabaloo. Some people showed pity, some laughed. But a woman came running, furious at everybody who watched, shouting at them to go away. She ran into the shop and brought out a man, barely able still to walk upright, but worked up a demonic rage. He tried to lunge at and attack some of the men who still laughed at him, but his knees gave, and he lurched without control, until his wife grabbed him by the arm and dragged him away.

The next day, she returned with a dozen women or more, attacked the tea-shop owner’s wife as the husband watched helplessly, and then broke, one by one, all the clay pots used by the tea-shop to brew raksi. Her husband had failed to come home two nights before that, because he had drank a full jerry-can of raksi brewed from maize mash and coarse molasses – called bheli – and blacked-out. His call-break playing friends had put him into a burlap sack and sewn him in, until, sometime around noon the next day, with yet another round of call-break going on, he had awoken to a very personel hell, of being bound and blinded, not understanding what had happened to the world outside, or if he was still alive, or if he wasn’t bound in a womb that opened to a hell of harsh, bright lights; loud, jarring noises; and a headache that recalled the blow dealt to Abel by his jealous brother. It was the first time I saw a man thoroughly humiliated because of his drinking habit. But that moment of revelation that there was a mad world beyond the ordered lives of the grown-ups.

The next day, she returned with a dozen women or more, attacked the tea-shop owner’s wife as the husband watched helplessly, and then broke, one by one, all the clay pots used by the tea-shop to brew raksi. Her husband had failed to come home two nights before that, because he had drank a full jerry-can of raksi brewed from maize mash and coarse molasses – called bheli – and blacked-out. His call-break playing friends had put him into a burlap sack and sewn him in, until, sometime around noon the next day, with yet another round of call-break going on, he had awoken to a very personel hell, of being bound and blinded, not understanding what had happened to the world outside, or if he was still alive, or if he wasn’t bound in a womb that opened to a hell of harsh, bright lights; loud, jarring noises; and a headache that recalled the blow dealt to Abel by his jealous brother. It was the first time I saw a man thoroughly humiliated because of his drinking habit. But that moment of revelation that there was a mad world beyond the ordered lives of the grown-ups.

I wanted to visit that mad-land, that topsy-turvy which could make any straight-faced man into a fool in a burlap sack.

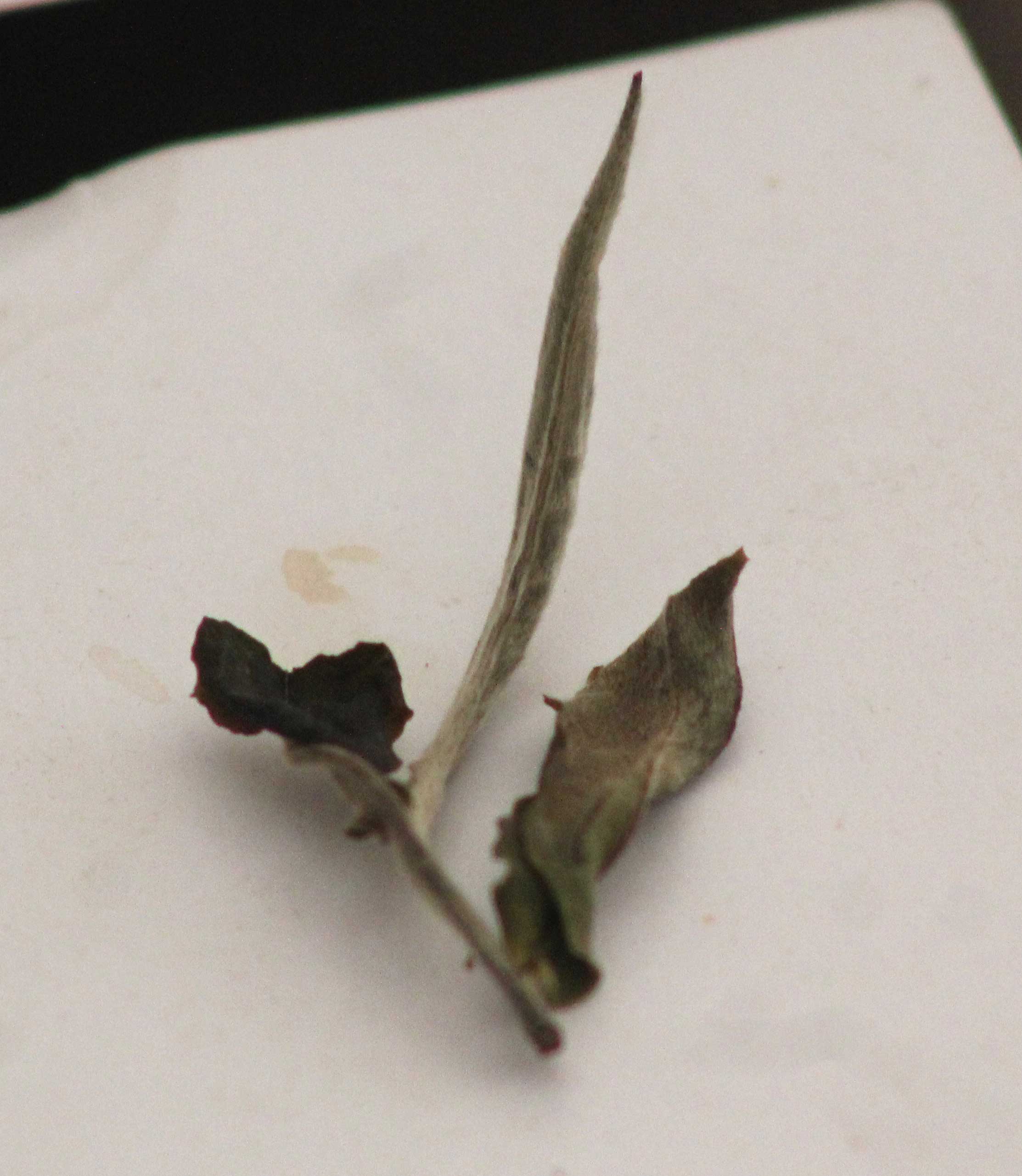

The smells of my childhood each had its own meaning: there was the day’s fodder grass stuck to Mother’s back, in which I could count the four or five kinds of grass that she fetched each day. The cattleshed was away from the hog-sty, and they each had a different pull on the nose. But the most intriguing smell came from a corner just outside the sty, away from the stench of hog-swill. There, every few weeks, Grandmother dumped a copper vat full of spent millet mash. Something between the aroma of fresh bread and the taste of fog in autumn, the smell of cooked and clean mash drove the hogs crazy. Solely for the reason that it was food for the porky lot, Grandmother forbid me and my cousins from scooping up the warm mash from the cauldron and eating it. Think of it as the millet left behind after a good round of tongba: it is still food, and if you eat enough of it, you will probably get drunk. We’d scoop the mash into bamboo cups and run away to the river, greedily eating it and doing cartwheels in the sand. I remember being lifted from the warm sands and being carried away over the hills. Then I remember the strange warmth and numbness as I urinated. My attachment to my penis grew stronger that day, and has remined just as strong. But alcohol doesn’t always help anymore: sometimes, like so many have written elsewhere, it makes one want, but it wants for the make.

There was an uncle, a man whose name I don’t remember because he was known to me simply as Kaka, who climbed down from the heights of the lek (mountaintop) to work the fields of a school-teacher. Kaka never started his work without two sources of energy and sustenance: a bowl of thick jaand of wheat, and a goodly chillum of ganja grown at three thousand meters above sea-level. One filled his blood with the fuel for a hard morning’s labor, and the other allowed him to work for hours without breaking his concentration. That man’s sweat went into the crops that fed two families – sustained by thick jaand and pungent ganja. Much later, drunk on the memory of the kind man, I attempted the same – a nice numbing of the senses, and the fire of two glasses of warm kodo in my belly before climbing a hill. Didn’t work: the fulcrum of alcohol has to sit between the man and his labor or way of life. When we drink to pretend to be somebody we aren’t, alcohol spurns us, sends us reeling to the dust beneath its feet. What we drink to forget the mundane has a stronger relationship with the depths in ourselves that we can’t pretend to have familiarity with.

There was an uncle, a man whose name I don’t remember because he was known to me simply as Kaka, who climbed down from the heights of the lek (mountaintop) to work the fields of a school-teacher. Kaka never started his work without two sources of energy and sustenance: a bowl of thick jaand of wheat, and a goodly chillum of ganja grown at three thousand meters above sea-level. One filled his blood with the fuel for a hard morning’s labor, and the other allowed him to work for hours without breaking his concentration. That man’s sweat went into the crops that fed two families – sustained by thick jaand and pungent ganja. Much later, drunk on the memory of the kind man, I attempted the same – a nice numbing of the senses, and the fire of two glasses of warm kodo in my belly before climbing a hill. Didn’t work: the fulcrum of alcohol has to sit between the man and his labor or way of life. When we drink to pretend to be somebody we aren’t, alcohol spurns us, sends us reeling to the dust beneath its feet. What we drink to forget the mundane has a stronger relationship with the depths in ourselves that we can’t pretend to have familiarity with.

One of the fondest taste of raksi I’ve been privileged to remember was from a Tamang woman in a village above Kapan. It was the day of Shiva Ratri, and a couple of friends had decided to walk through the national park for a day hike. It started drizzling. A wisp of smoke and the smell of fermented wheat lifted skywards from behind a house. I took my friends to the fire. To have the drizzle settle on your face and hair and to dry by a fire where raksi was brewing! The lady tending to the brew took heart at our simple joy and scooped up fresh, warm raksi right from the receptacle. It was also the taste of gratitude that I remember, and the laughter afterward.

I had a lover once. She didn’t drink much, but when she did, a couple of glasses of red wine made her ravenous. She’d take a swill of wine, and I’d drink the blood-red liquid from her mouth. She’d pour wine on her throat and watch me watch it trickle down, past the clavicle, over the breasts and the navel. I’d kiss her until no red stained her. She loved to leave marks on my arms. The next day, I’d smell wine in my hair and caress the bruises she’d marked me with. To me, red wine is the kiss of a woman with teeth stained purple and a mad lust in her breath and my taste on her tongue.

had a lover once. She didn’t drink much, but when she did, a couple of glasses of red wine made her ravenous. She’d take a swill of wine, and I’d drink the blood-red liquid from her mouth. She’d pour wine on her throat and watch me watch it trickle down, past the clavicle, over the breasts and the navel. I’d kiss her until no red stained her. She loved to leave marks on my arms. The next day, I’d smell wine in my hair and caress the bruises she’d marked me with. To me, red wine is the kiss of a woman with teeth stained purple and a mad lust in her breath and my taste on her tongue.

With a piglet in a cane cage and two roosters under the arms of elders, we climbed past the thin mist and into the bright sun on a mountainside. We walked for four hours, not a drop of water or crumb of food in our mouth, until the mere act of stopping for breath made the mouth water and chase away thirst. After another hour of preparing and finishing a puja to the mother goddess who protected those of us living in the valley, we walked to a stream that gurgled out of sleek rocks and put lips to water. It was cold water, cold and sweet, cold and fragrant with the smell of earth and fern roots. Thus quenched, we returned to the shrine where the elders had doled out small quantities of raksi in bohotas, leaf-bowls. The fatigue and hunger sent the alcohol rushing to the brain. Below us, the valley was splendidly lit by the noon-time sun. I remember turning with reverence to the goddess, wondering why she would show the kindness of protecting us, mere mortals made of dust. Grandfather poured a measure of raksi over a stone by the goddess’ shrine. My mouth watered again.

Dor Bahadur Bishta posited that it must be because a group of people in preferred the slow-moving sort of cattle that they got around to fermenting food, while another group preferred the fast-moving sort, and came to abhorring fermentation. Take the ethnic groups from the hills and mountains: they raised pig and chicken, difficult to march over a day’s walk, and they also fermented roots and leaves and beans and grains. Fermentation helped preserve calories and store them conveniently, while also making it possible to, well, get drunk and very happy. That is why a Tamang herdsman above Syafru will have grown a faint yellow line of moustache by eleven in the morning, and that is why old men sit on the bench outside the Patan Museum and watch the endless parade of people that pass. That is what makes people open their hearts to strangers, to scold them and call them closer to the fire, and give them a brimming dabaka of thick, nourishing jaand. It has always brought people together more than it has led to rifts.

But, things have changed. I find the group of young men sitting at a riverside ‘resort’ along Trishuli and ordering beers after beers; a strange lot: they don’t laugh, they don’t talk as much. For them the drink is mere accessory; an expensive one, bottled and brought to the table by a money-minded multinational company. How sad is the man in the city who buys a half-bottle of vodka to take home and drink on his own, trying to send himself to sleep! He isn’t in the bosom of his lover, or in the embrace of his friends. He isn’t even among friendly strangers. He is alone in a city; when he meets the eyes of a neigbour, they nod cutrly instead of making fun at each others. I have seen them make way for each other as they both try to find the way home, blind drunk and without anybody to talk to. Alcohol is merely the lens: the suffering is already inside each of us.

So, the morose end always awaits. In the absence of the wonderment of the first encounter, or of a feverish lover in our arms, or of the cold and clear light of a high mountain where even the goddess asks for a taste of the best brew, or in the absense of friends who increase the effect of inebriation, we sit lonely, trying to communicate with something elusive and unknowable, quite sobered up and therefore in horror. We await a rescue. The first hint of aroma, bubbles rising from the bottom of a tongba tankard, the gurgle as wine swishes around in a glass, the just-so velvet manner of whiskey eroding a piece of ice. These we await until we can unite in the noble goal of banishing sobriety to the eterworld where it belongs. Then we can bring to the surface our true friend, the child of Soma and Bacchus and, descended of Bhairava and goddesses who made marcha. It is impossible to write about drinking without being a little drunk on life itself.