Back in ’09, the associate editor asked me to work up an article using the earliest memories of some Nepali writers who had contributed short essays on the subject. We called it ‘Early Memories, Nepalese Childhoods,’ which saw print in December 2009, in the magazine’s 100th anniversary issue. That effort being well enough received, he solicited some first impressions of Nepal by expatriates. In the interim, now as a contributing editor he’s asked me to take on the task of working up a repeat performance.

I’ve taken a slightly different approach this time. I’ve interpreted the term “expat first impressions” liberally, to include brief accounts not only by recently arrived expatriates, but from some of the very first Westerners to visit Nepal from old books. One was the Italian Jesuit priest, Fr. Ippolito Desideri, who arrived on foot, overland from Tibet, in December 1721. His trek into Nepal took him from Kuti (Nyalam), just north of the Tibet border, down the old trade route along the Bhote Kosi river gorge to Kodari, and over the hills to Kathmandu. While the Bhote Kosi river route is easily traveled today on a modern road, in Desideri’s day it was dangerous and required scrambling by foot along “frightful precipices” forcing his party to climb up and down the cliffs “by holes just large enough to put one’s toe into, cut out of the rock like a staircase. At one place,” he writes, “a chasm was crossed by a long plank only the width of a man’s foot, while the wooden bridges... swayed and oscillated most alarmingly.” Desideri’s An Account of Tibet was written as his journal almost three centuries ago, but was not published until 1932.

The second account is by Joseph Dalton Hooker, a British naturalist, who described his explorations in eastern Nepal in his two volume Himalayan Journals, published in 1855. It is the scientist’s perceptive account of his journeys and botanical findings in the far eastern Nepal hills, which he entered from Darjeeling.

The collection of ‘Expat First Impressions’ are continued in three sets. The second installment (next month) features the first memories of Nepal by the American priest, Fr. Marshall Moran (founder of St. Xavier Godavari and Jawalakhel Schools), on his first visit to Kathmandu in 1949. Then, we meet Peter Schmiediche, a German agriculture development specialist who worked in the hills of Gorkha District for seven years, starting in 1963-64.

The third and final installation features two more recent stories by professional writers. One is by Murray Laurence, an Australian educator and travel writer, who has published two humorous books on his wanderings. The other is by Carrie-Ann Tkaczyk, an American Peace Corps Volunteer, who taught schools in Nepal for two years (1990-93).

Each story in this three-part series is a unique snapshot of one person’s first impressions of Nepal, and each provides us with a glimpse of a specific place and an earlier time.

Desideri’s View (1721-22 AD)

One of the earliest Europeans to describe in detail the impact of his first visit to Nepal was the Italian Jesuit Fr. Ippolito Desideri, SJ. He stayed one month in the winter of 1721-22 as a guest of Capuchin Catholic friars living in Badgao (Bhatgaon, or Bhaktapur). His account reveals a very old Nepal, far removed in time and circumstances from today. Desideri was a religious man who looked down upon all whom he considered to be “superstitious... heathens”. His story is excerpted from a longer description of Kathmandu valley customs and living standards:

We arrived at Kathmandu on the twenty-seventh of December, where the Very Reverend Capuchin Fathers received me with much charity, and kept me in their hospice with great kindness for nearly a month. The Kingdom of Nepal owes no allegiance to any foreign power, but is divided among three Kinglets who reside in the three principal cities; the first at Kattmandu; the second at Badgao [Bhatgaon], the third at Patan....

The chief people in Nepal, after the petty Kings are the Guru and the Pardan [Pradhana]. The former are priests and spiritual directors, but are allowed to marry and are not numerous. Every Kinglet has his special Guru, to whom he turns for advice. The Pardan are ministers, officers of the law and nobles. The rest are merchants whose business is in Nepal, or who have dealings with Thibet or Mogol. These Neuars are active, intelligent, and very industrious, clever at engraving and melting metal, but unstable, turbulent and traitorous... They wear a woollen or cotton jacket reaching to the knees and long trousers down to their ankles, a red cap on their head, and slippers on their feet; when it rains men and women go barefoot....

Rice is their principal food, either cooked, or crushed and roasted; the latter serves as bread and as a relish. If they eat meat it is generally buffalo. They drink water and a nasty liquor made of a certain millet which grows in this country and is the staple food of the very poor. A kind of beer is also made from wheat or rice, and some drink arac distilled from raw sugar. Much rice is grown as well as wheat, sugar cane, vegetables, and fruit....

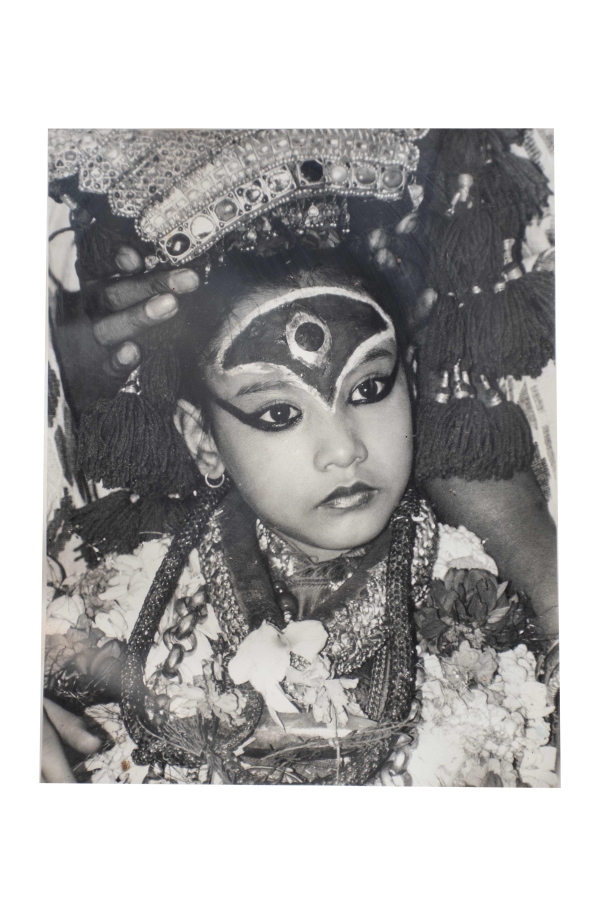

They are very superstitious in all things, futile observers, and utter heathens... They write on paper with an iron style and know nothing of printing, but have numerous manuscript books. False Gods are worshipped by them, such as Ram, Mahadeo [Mahadev]. Brumma [Brahmah], Viscnu [Vishnu], Bod [Buddha], Bavani [Bhavani], and many more. At a certain quarter of the moon they offer an infinite number of sacrifices to the Goddess Bavani of sheep, goats, and buffaloes, which they allow to rot, and then eat with great devotion as precious relics. On that day the number of animals slaughtered in the whole Kingdom amounts to many millions....

Although so many animals of all kinds are killed for sacrifices and food, yet the people treat them with the greatest consideration; they are not made to work, as everything is carried by men. To their false Gods they offer horses and oxen; but instead of killing them they let them loose to go where they will. The beasts wander about the fields and do much damage to rice, wheat, and other cereals; for they belong to the Deuta (as the Gods are called) and may not be driven off or disturbed; also this people have a most superstitious veneration for cows....

At Bhatgaon, Fr. Desideri was graciously received by the local king who “twice sent for me, showed me much honour,” he says, “and when I left, gave me a letter to the King of Bitia (Bettiah), whose kingdom I was to traverse; he also gave me an escort to protect me until I had crossed the uninhabited mountains.” His immediate destination after Nepal was the Christian mission in north India, via Bettiah to Patna. Ultimately, he returned to Rome, the center of world Catholicism.

Hooker’s View (1848 AD)

The following richly descriptive account by the British naturalist, Joseph Dalton Hooker, clearly reflects an immense scientific curiosity by someone for whom the natural wonders of the world botanical, zoological, and cultural were worth describing in detail. Hooker was a colleague of Charles Darwin, and of the (then) recently retired British Resident representative to Kathmandu, Brian H. Hodgson (well known for his own scientific writings on Nepalese culture, languages, and natural history). In 1848, from Darjeeling, Joseph Hooker petitioned the “Nepal Rajah: “to grant me honourable and safe escort through his dominions; but this,” he goes on, “was at once met by a decided refusal, apparently admitting of no compromise.” Nepal appeared firmly closed to outsiders, but that did not deter Hooker. Almost immediately, with the assistance of British officials, he applied again for less expansive permission “to visit the Tibetan passes, west of Kinchinjunga; proposing... my return through Sikkim... [T]his request was promptly acceded to, and a guard of six Nepalese soldiers and two officers was sent to Dorjiling to conduct me to any part of the eastern districts of Nepal which I might select...” On October 27, 1848, Hooker’s party left Darjeeling, crossed into eastern Nepal, and proceeded northward towards the passes into Tibet.

There is a bit of the colonial in Hooker’s style of travel: “My party mustered fifty-six persons, including myself,and one personal servant, a Portuguese half-caste, who undertook all offices, and spared me the usual train of Hindoo and Mahometan servants.” The colonial viewpoint also infects his copious and detailed writings, especially where he compares his (more civilized) circumstances with those of his Lepcha and Bhotanese botanical collectors and coolies who, in his view, lived lives that were “native, savage, and half-civilised.”

After departing “Dorjiling” he traveled “in a westerly direction, [and] descended into the Myong valley in Nepal, through which flows... a tributary of the Tambur. This valley,” he writes, “is remarkably fine... [with an] open character and general fertility... At its lower end, about twenty miles from the frontier, is the military fort of Ilam, a celebrated stockaded post of the Ghorkas: its position is marked by a conspicuous conical hill. The inhabitants are chiefly Brahmins, but there are also some Moormis, and a few Lepchas...” He was welcomed by a local official with the title of Kazee who sent him “the usual present of a kid, fowls, and eggs...”

Hooker continues:

The scenery of this valley is the most beautiful I know of in the lower Himalaya, and the Cheer Pine (P. longifolia) is abundant, cresting the hills, which are loosely clothed with clumps of oaks and other trees, bamboos, and common English bracken. The spurs separate little ravines luxuriantly clothed with tropical vegetation, through which flow pebbly streams of transparent water. The villages, which are merely scattered collections of huts, are surrounded with fields of rice, buckwheat, and Indian corn, which latter the natives were now storing in little granaries, mounted on four posts; men, women, and children being all equally busy. The quantity of gigantic nettles (Urtica heterophylla) on the skirts of the maize fields is quite wonderful: their long white stings look most formidable, but though they sting virulently, the pain only lasts half an hour or so. These, however, with leeches, mosquitos, peepsas, and ticks, sometimes keep the traveller in a constant state of irritation.

However civilised the Hindoo may be in comparison with the Lepcha [of neighboring Sikkim], he presents a far less attractive picture; he comes to your camping-ground, sits down, and stares, but offers no assistance; if he brings a present he expects a return on the spot, and goes on begging till satisfied. I was amused by the cool way in which my Ghorka guards treated the village lads...

Some days later Hooker and party set off northward from Ilam to Wallanchoon near the border with Tibet:

The ascent was gradual, through a fine forest, full of horn-bills (Buceros), a bird resembling the Toucan. Water is very scarce along the ridge... and [we] were at length obliged to encamp at 8,350 feet by the only spring that we should be able to reach....

While my men were forming their encampment, I ascended a rocky summit, from which I obtained a superb view... [of a spectacular sunset]. Immediately beneath a fearfully sudden descent, ran the Daomy River, bounded on the opposite side by another parallel ridge of Sakkiazung, enclosing, with that on which I stood, a gulf from 6000 to 7000 feet deep, of wooded ridges which, as it were, radiated outwards in rocky spurs to the fir-clad peaks around. To the south-west, in the extreme distance, were the plains of India, upwards of 100 miles off, with the Cosi meandering through them like a silver thread.

The firmament appeared of a pale steel blue, and a broad low arch spanned the horizon, bounded by a line of little fleecy clouds; below this the sky was of a golden yellow, while in successively deeper strata, many belts or ribbons of vapour appeared to press upon the plains, the lowest of which was of a dark leaden hue, the upper more purple, and vanishing into the pale yellow above.... As darkness came on, and the stars arose, a light fog gathered round me, and I quitted with reluctance one of the most impressive and magical scenes I had ever beheld.

Returning to my tent, I was interested in observing how well my followers accommodated themselves to their narrow circumstances. Their fires gleamed everywhere amongst the trees, and the people presented an interesting picture of native, savage, and half-civilised life. I wandered amongst them in the darkness, and watched their operations; some were cooking, with their rude bronzed faces lighted up by the ruddy glow, as they peered into the pot, stirring the boiling rice with one hand, while with the other they held back their long tangled hair. Others were bringing water from the spring below, some gathering sprigs of fragrant worm-wood and other shrubs to form couches―some lopping branches of larger trees to screen them from nocturnal radiation; their only protection from the dew being such branches stuck in the ground, and slanting over their recumbent forms... The Ghorkas were sprightly, combing their raven hair, telling interminably long stories, or singing Hindoo songs through their noses in chorus; ...they seemed quite the gentlemen of the party...

Desideri’s first impressions are excerpted from his An Account of Tibet (edited by Filippo de Filippi, London, 1932), and Hooker’s are from his Himalayan Journals (2 vols, London, 1855).

The series will be continued next month. The series editor, Neale Bates, is an occasional contributor to ECS Nepal. His email is nealebates@gmail.com.