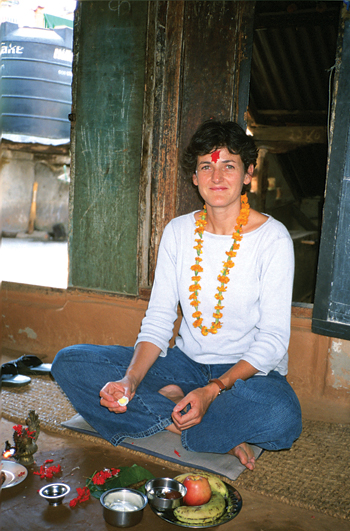

Isabella Tree’s book, The Living Goddess: A Journey into the Heart of Kathmandu came out in April. Tree spoke to Kapil Bisht about coming to Kathmandu as a teenager, pursuing her subject for over a decade, and the experience of writing a book about a Living Goddess.

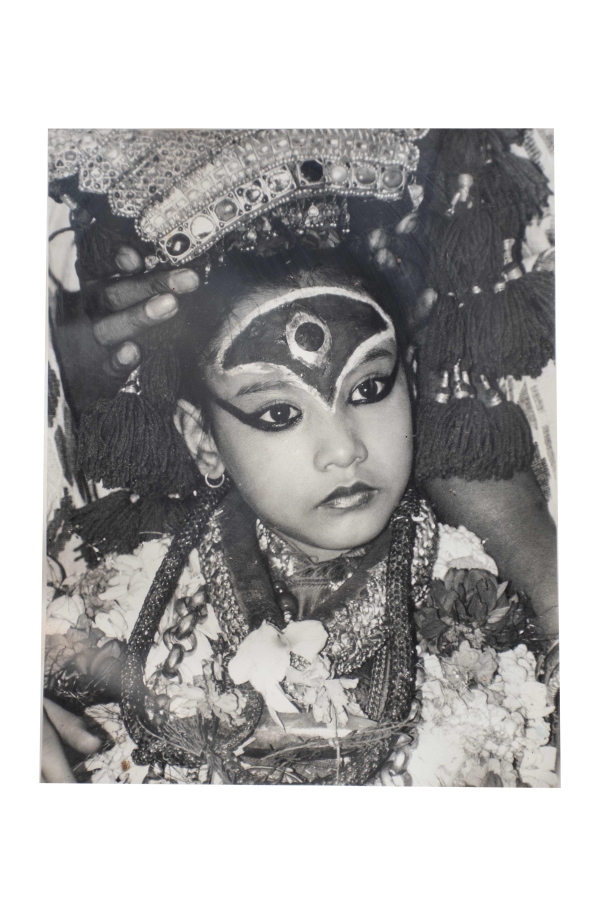

Any tourist who has been in the courtyard of the Kumari House in Kathmandu would love to go beyond the sign that says ‘FOR HINDUS ONLY.’ Although Isabella Tree would have loved to do that as well, she was drawn more to the little girl with the stolid expression who appeared at the window with the red curtains. She wanted to know more about her. She also wished to find out if the wild rumors circling the Kumari tradition had any truth to them. She wanted, in short, to know more about an institution that existed in a cocoon of secrecy.

It took Tree over a decade to know what she wanted to know, and to write a book about it.

You first saw the Kumari when you were a teenager visiting Nepal. When did you decide to write a book about her, because your next trip to Nepal was 14 years after you first saw her?

I first came to Nepal in 1983 and lived with friends in a rented flat on Freak Street. That is when I first had darshan of the Kumari. That was the germ of the idea, the seed of the whole obsession began then I suppose. When I had the chance to come back, in 1997, I knew I wanted to see the Kumari again. That was one of the reasons I came. I had been longing to come back to Kathmandu, but there had been university, marriage, and children. Then I came here on a two-week holiday with my husband. That’s when I met Rashmila Shakya [the former Kumari, who co-wrote, with Scott Berry, From Goddess to Mortal. The meeting reignited my interest in the Kumari.

After meeting Rashmila I understood a lot more about what happened to Kumaris after they were replaced. But I still did not understand what happened to them while they were in the Kumari Chhen [Kumari House] or what the tradition was really about. So, in 1997, I thought that was as much as I would ever know. But then the royal family massacre happened in 2001, and suddenly I realized that there was the Maoist threat. They had sworn not to worship the Kumari. I thought that the Living Goddess tradition might end. The whole political situation was so uncertain. So I wanted to come back and see if I could find out anything else. Paradoxically, the political turmoil opened up doors for me because I think the guardians of the Kumari tradition – the caretakers and the tantric priests – were also beginning to feel pressured. They didn’t know what the future was going to hold, so they felt, I think, that they needed to open up just enough to tell the outside world that this was a tradition worth preserving. So there was a new kind of openness, an unprecedented willingness to embrace people from outside—not to expose any tantric secrets but certainly to dispel some of the rumors that were threatening the Kumari tradition.

The Kumari system is bound up in so many esoteric rituals. It’s part of religion and is inextricably bound with Newar culture. As a writer, was it difficult to maintain objectivity while researching and writing the book because understanding such a tradition requires, if only partially, believing in it?

It’s a real dichotomy, I think. With Tantra, at least, it will remain a closed book to me. I can’t even say I’ve scratched the surface because you can’t understand it unless you’ve received initiation. And once you’ve received initiation, you’re committed to secrecy. Uddhav Karmacharya, the tantric priest of the Taleju Temple, was adamant that I shouldn’t be writing about the Kumari, that this wasn’t something that should be transmitted in a book. But he eventually softened and opened up and explained the tradition to me. But I did feel that that if I went any further and started to experience it [Tantra] and believe in it, I wouldn’t want to write a book. You have to stay objective while writing a book.

You say you wrote this book because you wanted to better understand the Kumari belief system. But did you have a hard time reconciling with the fact that this system involved taking a three- or four-year-old child away from her family? Was accepting the system as hard as understanding it?

You say you wrote this book because you wanted to better understand the Kumari belief system. But did you have a hard time reconciling with the fact that this system involved taking a three- or four-year-old child away from her family? Was accepting the system as hard as understanding it?

I tried not to be that subjective. When I first came here as a teenager, I reacted like many Westerners, and actually many Nepalis, do. They see a little girl at the window, and they think, captive child, child abuse. They leap to all sorts of conclusions. In a funny kind of way, the Kumari is like a blank screen. If we don’t understand what is going on – she has a very passive face; she doesn’t smile or react like a normal child – quite often we project our own insecurities, our fears and anxieties on to her. We think, this shouldn’t be happening. And because something awful is happening to little girls all over the world, one assumes something awful is happening to the girl in the Kumari House too.

When I came back later, as an older, more mature woman, I began to see that we cannot judge the tradition from outside because you cannot separate the tradition from the belief system. The Kumaris themselves believe it is their duty, their dharma, and their families believe they are born to this and that it is a great honor, that they are doing this for the good of all sentient beings. I interviewed an ex-Kumari just this morning, and she was telling me how this is empowering for women and serves as a message for men in society on the standard of respect they need to show to women and children. So it’s quite the reverse of what a lot of people assume. This is a flagship for feminism. She [the Kumari] is a reminder to people that every single little girl is a goddess.

It took you 13 years to research and write this book. How has that changed you as a person?

I have had to learn to be a lot more patient than I used to be. In a way one of the most impressive things that happened to me was kneeling [before the Kumari] and submitting to an intelligence and knowledge that is higher than you, even if one doesn’t particularly believe in it or understand it. The submission of one’s ego—I have learned a bit from that.

The other three books you’ve written: one is the biography of an English ornithologist and the other two are about your travels in Papua New Guinea and Mexico. What was it like doing those books and then your book on the Kumaris?

Looking back on them I guess I’ve become more interested in anthropology as I have gone along. Historical contexts have always interested me. When I kicked off with my book about the Victorian ornithologist [John Gould] what interested me was his character and the times and the culture in which he lived. And because he’d done books on the birds of New Guinea, my research took me there. There, I found myself in a tribal society and that sort of kicked off an interest in cultures other than my own. So when I went to Mexico I once again wanted to look at the indigenous side of Mexico, which is extraordinarily rich and diverse, and there is very little written about it. This, in a way, was one step towards writing about cultures. It was a natural progression actually because it was getting less about the flippant travel writing, few anecdotes about funny stories in taxis. There are probably fewer jokes in my books nowadays.

There have been drastic changes in Nepal since you first came here or even after you began writing your book. Nepal is, constitutionally, a secular nation now. And there will be a generation soon that will grow up with Facebook as the bigger presence in their lives than something like the Kumari. Do you see the Kumari tradition surviving in the near future?

I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive. Chanira Vajracharya, the ex-Patan Kumari, has been friends on Facebook with my daughter for years—even when she was Kumari. I think what really struck me about the Newar traditions is that there is a very strong sense of following the ritual procedures of their ancestors. And yet there is also a kind of amazing ability to compromise and find a way into modern life, to change with the times. When I was watching the Kumari tradition from 2001 onwards, for the first few years I thought, Gosh! This could be the end. But since 2005 I have seen this upsurge of confidence and interest from young Newars in the Kumari system. Who knows what it will be like in 20 or 30 years? But I think it’ll be still here.

You’ve presented many aspects of the Kumari tradition as the priests, the caretakers and the parents of the Kumaris see it. How hard was it to comprehend their points of view?

Well, I hope I have seen it as they see it. One does that whenever one talks to someone. It’s a matter of empathy. If you really want to understand someone else’s point of view, you have to put yourself in their position. The initial interviews I had, for example with Rashmila and her parents, I didn’t understand very much so she was talking to me on a different level. She was simplifying things. And sometimes perhaps if you don’t know enough about the background to your subject, people tell you what they think you want to hear. I think that is a big problem. But the more you get to know someone and the more trust develops between you two, the more someone opens up, and the more you can understand what they’re trying to say.

While researching about a culture or a place to which you are alien, you’ve got to find an entry point. You have written about New Guinea, Mexico, and Nepal—places whose native languages you didn’t speak. Do you have some special trick that you’ve developed to help you “get in”?

No. I think it’s just a question of finding the gatekeepers, the people who can help you open the doors. In Mexico, for instance, knowing how to speak Spanish was no use because many of the indigenous peoples I spent time with were speaking their own separate language. For all those different cultural aspects of Mexico I had to find someone who was the gatekeeper, someone who wasn’t just a translator but who could bridge the cultural gap. And I think it’s the same here. So I found people – like Kashinath Tamot – who have a deep understanding of Newar culture.

You interviewed the royal astrologer and priests—people who look up astrological charts to determine dates for important events. Were you ever tempted, especially because it took you so long to write the book, to look up the charts for a publication date for your book?

No, I didn’t. But I threw a party to celebrate the book launch in Kathmandu and to thank the people who had helped with the book. It was the Kumari caretakers who came up with April 7 [2014] as an auspicious day. It was Chaitra Dashain, one of the days when the Kumari goes out in her palanquin. I had a special blessing that day. I offered her [the Kumari] my book, which she accepted, thank goodness! If she hadn’t, I would have felt like the king without the tika!