Following in the footsteps of many youngsters of Dolakha, 135 km northeast of Kathmandu, Rameswor was drawn to the big metropolis after passing his School Leaving (SLC) exams. Although Charikot, the Dolakha District headquarters, had a college at the time, most young men of the town could not resist the glitz and glamour of the metro. At age 17, Rameswor joined the mass exodus to the capital. Besides scores of colleges to choose from, Kathmandu also promised odd jobs for all, whatever their academic qualifications. In the capital, rural youngsters usually find temporary residence with friends or relatives who have also migrated to the city in their teens. For my cousin Rameswor, my family was the closest. He stayed with us for about seven months, and then moved into a dera (rented room) with a friend.

For near on 20 years Rameswor worked in a private company and also pursued his further studies, though somewhat haphazardly. Now married and a father of three, he runs a small catering business of his own. And all these years he has never missed a trip back home to Dolakha, to celebrate Dashain. I asked him, "How long have you been doing this?" He scratched his head, mentally calculating it up, and said, "Must've been more than 20 years, dai (brother)."

This past year was no different. With only a day left before the start of the Dashain holidays in October, Rameswor set about to wrap up the last minute work at the office, then bought a bus ticket and a few things to take back home from the bazaar including some medicines for his ailing mother and, not least, a new sari and necklace for his wife Parwati.

HOMEWARD BOUND

On Fulpati (the first day of the holidays), a bus packed to capacity with a boisterous group of friends and relatives headed out for Dolakha. While the bus, laden with the holidaying bunch, sped along the Arniko Highway and a happy Rameswor was tucked comfortably into his seat thinking about home and family, it never crossed his mind that a surprise beyond his wildest imagination might be waiting his arrival.

The bus arrived in Dolakha in less than six hours. Heaving his bag onto his shoulder, he hastened down the hill to his house at Chamsali tole. "Baba's come! Baba's come!" bellowed Rameswor's son Aleen, as he and Parwati rushed to greet him. Another son, Ayush, and daughter Alina grinned from ear to ear to see dad home.

For Rameswor, Dashain began with the usual puja at the Bhimeswor Temple followed by social calls to uncles and sasurali (wife's family), finding a stout goat for sacrifice and feasting, preparing for the tika ceremony and spending the rest of the time playing cards with friends and relatives.

IN A DILEMMA

On the third day of Dashain, Rameswor was invited for lunch at his 76 year old uncle Cheeni Bahadur's house. Once there and settled comfortably, Cheeni Bahadur broke the news: "Babu," he said, "I don't feel well and I'm afraid I won't be able to perform this year's Khadga Jatra (Sword Festival). Since you're the senior most amongst your brothers, it looks like you will have to take my place." The words fell on Rameswor like a bolt from the blue . "Kaka (uncle), since you've been performing for such a long time, I can't even imagine myself replacing you," he protested, somewhat shaken. "Ke garne? (What to do?)", his uncle replied, while a faint look of concern brushed the creases on his gnarled face, "My health has failed me and the right candidate, your uncle Shyam, is in no shape to assume the responsibility." Rameswor admitted to himself that his younger uncle Shyam, an alcoholic for some years, wouldn't stand a chance. But, still...!

All nerves, Rameswor's mind played havoc as all sorts of questions - to which he had no ready answers -- jostled in his head. "How on earth am I supposed to take up this responsibility? With zero experience to fall back on, will I be able to pull it off? What if I lose my nerve and fail at the last moment?" As these questions raced through his mind, he was jerked to attention by his uncle Cheeni's words: "You can do it", he said, as if reading Rameswor's mind. "Don't worry too much. I'll be by your side to guide you." And, despite his muddle about the new responsibility and with his uncle's encouragement Rameswor walked back to his house.

Rameswor's fears were logical enough. He was to assume the formidable responsibility of performing as the goddess Bhagwati, the Power of the Supreme Being, the Divine Mother, the Savior of Mankind from evil and misery. Enacting this great deity live was no mean feat. It calls for a grueling march through the town from nine in the morning till sundown brandishing a sword with one hand while grasping a shield and pirouetting down the street to the tune of traditional instruments, barefoot and on an empty stomach. This, however, did not daunt Rameswor. Only a nagging doubt about his ability plagued him. Nonetheless, "No matter what, I'll not bow out. This is my destiny", the determined Rameswor said to himself.

While Rameswor was going through all this, this scribe accompanied by my family also happened to be in Dolakha for the Dashain holidays. As word got out about Cheeni uncle's failing health and Rameswor assuming his place for the Khadga Jatra, I became excited and decided to cover the entire ritual with my camera.

JATRA BEGINS

The next day, as the sun tipped the towering mountains in the east, my watch read 7 o'clock am as I left for Rameswor's house. The morning looked bright and the weather crisp befitting the grand occasion, the day when Dolakha's Newar residents celebrate with great pomp and festivity the legendary Khadga Jatra. Initiated as early as 1784 BS (around 1727 AD) during the reign of King Jagat Jay Malla, this festival is observed on the day of Ekadashi (the 11th day of lunar fortnight of Ashwin, in October). This festival marks the triumph of virtue over the forces of evil as the gods set up a secret council to put an end to the terror begot by the danavs (demons). During the jatra (festival) pitched battles take place between the gods and the demons as young and old performers clad in traditional attire simulate the battle scenes. It all ends in the slaying of the demons, thus restoring peace and happiness among gods and mortals alike. With this traditional ritual, however, Kusules (beggars) and the Kansais (butchers), both considered a 'low caste', also form an alliance as the demi-gods are made to dance and sway to the age old traditional music that they play.

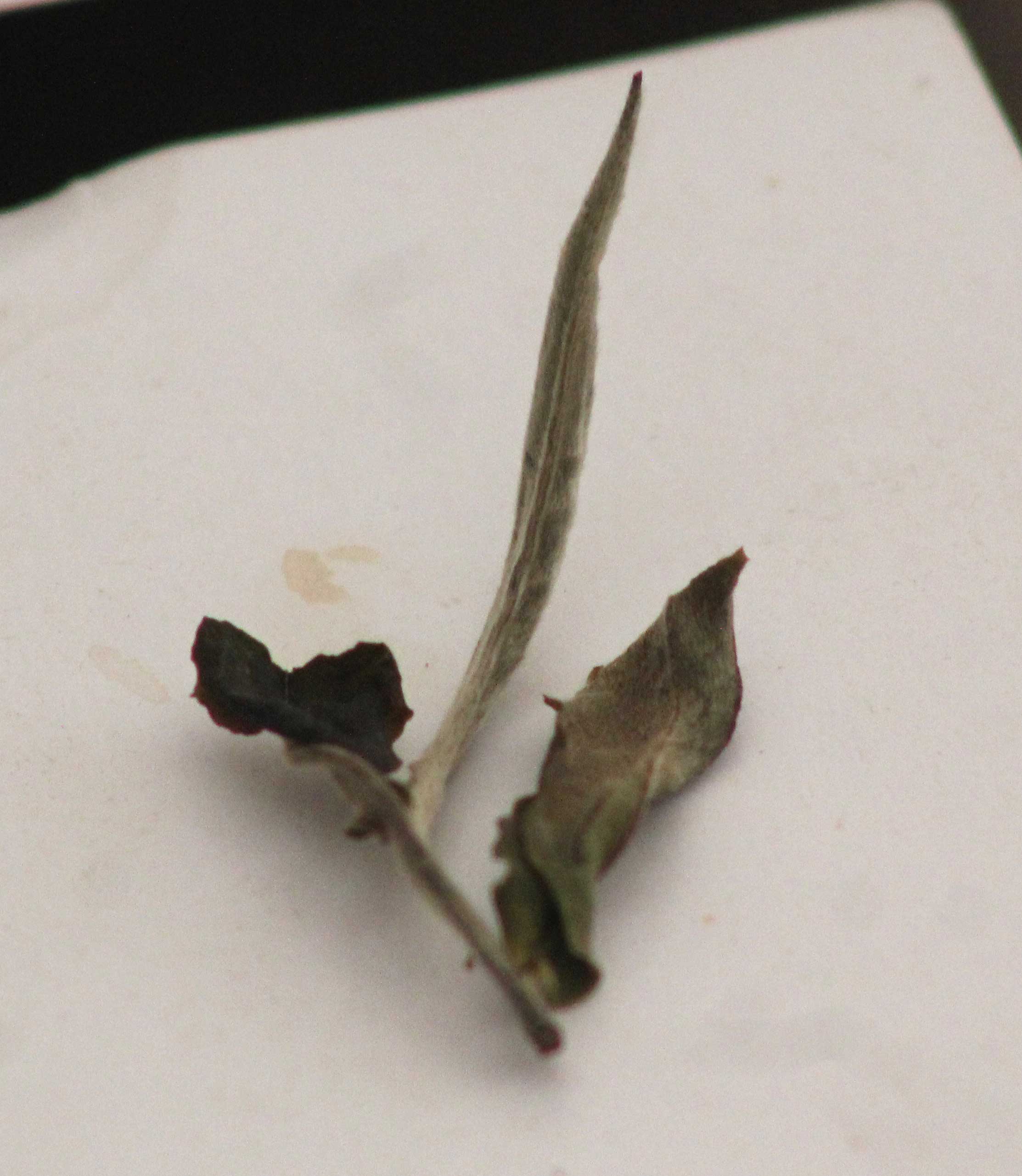

At Rameswor's house, quite a number of relatives and friends gathered to congratulate him and raise his spirits. Amidst a flurry of activity, the women fussed about the house while the men folk helped Rameswor into the traditional attire prescribed for the occasion. The costume consisted of a white daura (kind of shirt), a frock and a turban, and a patuka (a cloth belt) about his waist. As scads of artificial flowers and jamara stalks (young barley shoots) were tucked wreathlike into his turban, a garland of jamara was placed around his neck. Uncle Cheeni lent a hand in the dress ceremony and gave Rameswor last minute instructions, as the women prepared sagun, an offering of alcohol, egg and tidbits for good omen and luck. After the dress and sagun ritual, all of which lasted for almost an hour, Rameswor was all set to start.

ENACTING THE GODS

Rameswor, at the head of the procession, set out across town with uncle Cheeni, scores of local crowds and this scribe. From Chamsali tole we went towards the kulyan (where our ancestral deity is housed) past the historic Rajhiti ('royal stone water spouts'). Along the way, more people joined the procession. At the kulyan, Rameswor was again offered sagun as a group of five more elaborately dressed performers and a local band joined in. Now the team was led by the band of Kusules and the Kansais to the beat of a dholak (drum), sehenais (clarinets) and clashing cymbals. They crossed the stone paved street to an historic old house called the Rajkuleswor, or Taleju Bhawani. A puja ceremony with the ubiquitous sagun offering began there as the performers lined up for the ceremonial handing over of the weapons. Cameras flashed as photo enthusiasts competed to get the best shot. Rameswor, enacting the Supreme Bhagawati, was first to be handed a shield and sword; others were given only swords. At the forecourt of Rajkuleswor a steady stream of people poured in from all sides as the crowd grew.

The priests signaled Rameswor to start out. From here on he had to swing and sway to the traditional beat of the music wielding the sword and shield invoking the real goddess Durga. Time froze as Rameswor made his debut, while I waited breathlessly, fingers crossed and camera ready. The drummer went into a rhythmic lilt and the clarinets fell in with the beat. For a moment Rameswor hesitated. Then something propeled him and his feet sprang into a rhythmic tap and his body started gyrating as the tempo grew, and his arms swung from side to side with the sword and shield. I was so mesmerized that I forgot my camera, but recovering quickly I trained the lens on Rameswor as he threw his shoulders back, his chin held high, while his face glowed and his eyes glinted as he swayed to the music. For a moment I had an eerie feeling that the figure before my eyes was not the shy, self-effacing Rameswor whom I knew, but a stranger possessed. "I'm seeing a god," I said to myself and suddenly I felt a chill. The hairs on my arms stood on end. After three different themes, the music stopped with the clash of cymbals, and a stupefied Rameswor was led to one side. It was now the time for other warrior gods to perform and one after another they enacted the mock battle. The last to appear was the priest commander, called the Yakargan

BATTLING DEMONS

After this display, the performing gods with the Bhagwati (Rameswor) in the lead paraded across the street and the battle scene was rehearsed with short breaks. As the warring gods proceeded through various streets doing short work of the demons, more warrior gods joined as reinforcement. People tripped over themselves to get a closer look and touch the live gods and offer flowers.

Drenched in drama, the pageantry continued towards the famed Bhimeswor Temple. By then it was already past noon and the midday October sun seemed to sap the energy of the performers as volunteers offered water and fruit juice. Rameswor, too, looked a little weary, but when asked nodded to me to say he was fine.

The atmosphere was festive and the entire town of Dolakha bustled as people thronged around the streets to watch with consuming interest the jatra in progress. Besides the distinct native Newars, I saw Tamangs, Thamis, Chhetris and Brahmins in the crowd. Women, children, young and the old, all dressed in their best attire had come from nearby villages and settlements. Some came from farther away. I talked to a 10 year old Thami boy who had walked nine hours with his father to watch the festival.

By two in the afternoon I was famished, so my wife Radhika and my daughter Bulbul traded places with me so I could have some lunch. When I returned, the performers were in the forecourt of the Bhimeswor Temple. Rameswor was performing flawlessly, confidently flourished his sword and shield. In front of the temple there were three sacrificed buffalo carcasses symbolizing the slain demons. After Bhimeswor, the procession headed towards Devikot, a shrine that houses the goddess Tripura Sundari Bhagwati. Here the militia of gods advanced with Tripura Sundari Bhagwati's son, Batuk Bhairab as reinforcement. He is known for his ferocious fighting skill. From now on, wearing a buffalo intestine as a garland, Batuk Bhairab and the priest commander Yakargan wreaked havoc on the demons, while Bhagwati and her aides and other gods remained as bystanders.

TRIUMPH OVER EVIL

As the day wore on so did the stamina and strength of the performers, weighed down as they were by their unwieldy attire and weapons. Even the sun appeared relentless as it beat down upon them, not to speak of the groaning stomachs and the singed and painful soles of their bare feet. They appeared, however, as if they are no less than gods and gallantly burst into renewed frenzy wreaking vengeance upon the demons.

As the shadows lengthened and the day drew near an end, the goddess Bhagwati and her aides, parted company with the commander Yakarghan, Batuk Bhairab and a number of other gods and retraced their steps back to Rajkuleswor for the last part of the jatra. Amidst chanting of tantric verses by the priests, a kubindo (a kind of pumpkin) symbolizing a marauding demon, was placed in the forecourt to be hacked in two by the protagonist, the Bhagwati. Her aides follow suit. No sooner did Rameswor strike the pumpkin with his sword, however, than pandemonium broke out and before the other gods prepared to strike, the crowd rushed in to get their hands on the severed pumpkin. It is believed even a tiny piece of that miracle pumpkin, if fed to cattle, will stimulate fertility. The jatra came to an end as Bhagwati and her aides were ushered inside the shrine where they handed back their weapons.

That evening, Rameswor's house buzzed with friends and relatives. We sat around sipping Parwati's special home-brew (airak in local dialect), the millet liquor, while a weary Rameswor relaxed and beamed at the compliments that he was given. Poor Rameswor-he did not realize that after all that grueling punishment his body has taken, the next two days would be spent nursing his aching muscles and badly blistered feet. For Rameswor, however, this compares as nothing to the great accomplishment of having lived up to the proud lineage so sacredly kept over the generations by his forebears.

EPILOGUE

Party over, as I prepared to leave I could not hold myself back from asking Rameswor the question which wriggled like a worm in my mind all day. "Frankly, Rameswor, did you feel any different when you were performing? Did you feel for a moment that you were being guided by some unforeseen force?" The village elders in Dolakha still believe that some of those who perform in the Khadga Jatra, only the chosen ones, are visited by the gods. "Dai, I can't say for sure, but when I first stepped out from the doorway of Rajkuleswor, all jumpy and hesitant, something, some power, suddenly seemed to possess me and drove me to the waiting music. My mind just failed to register when I started performing and when I stopped. I came to my senses only when I was led to the side," he answered, pensively. Now it was my turn to puzzle over it all as I headed home. "Was it just a fancy of my mind or did I really see a god?" I wondered then, and even now as I wind up Rameswor's story. g

Ravi Man Singh is a freelance writer who lives in Kathmandu. He can be contacted at ravimansingh@hotmail.com.

Some lesser-known vegetable dishes from the southern plains

I’m not a vegetarian but I love vegetables. And whenever I get to the southern plains of Nepal, I try...