Inspiration, Innovation & Volunteers in Myagdi District

We finalized our plans at Mahabir Pun’s Center for Nepal Connection, a restaurant and networking hub in Thamel, upstairs along Mandala Street in the heart of Kathmandu’s popular tourist quarter. Mahabir, the “wireless guy”, briefs trekkers and volunteers there before trekking in Myagdi, his home district in the central hills. He tells his inspiring story with a quiet intensity and compelling zeal.

Mahabir’s story begins with the Nepal Wireless Networking Project, established in the early 2000s during the worst of Nepal’s recent political and social unrest. Since then, the project has connected over 150 villages to the Internet.

But Mahabir doesn’t much like being known primarily as the “wireless guy”. He recently told Debra Stoner, his biographer (at wirelessprophet.com), that he has “bigger goals” and doesn’t limit himself to wireless work. “It is just a tool,” he says, one that he worked on when there was no other means of communication.

We wanted to see the results of his wireless endeavors and bigger goals, especially what he has done to inspire villagers and foreign volunteers to improve local education, health and livelihoods. For that we had to visit Nangi village, Mahabir’s birthplace, where it all began. We also wanted to visit nearby Sikha village. A few years ago, as members of Friends of Nepal (a group of former Nepal Peace Corps Volunteers), we helped fund a wireless telemedicine link-up between the Sikha health post and Kathmandu’s Model Hospital.

The trek

We were four trekkers, plus guide and two porters. Dave and I, former Peace Corps Volunteers, were joined by two friends, Barbara, a science educator, and Bill, an adventurous former jet fighter pilot. The Annapurna Dhaulagiri Community Trail, also called Myagdi Ecotrail, is a scenic cultural adjunct to the Great Himalaya Trail across Nepal. By going in March, we hoped to see rhododendron forests in full bloom, in-your-face views of Dhaulagiri and Annapurna, the world’s 7th and 10th highest peaks, and local developments. We got all that and more.

From Pokhara, Chitra Pun, our guide, arranged a ride northwest past Myagdi’s Beni Bazar and the Hindu shrine at Galeshwar, to Rahughat. From there we walked; first on a long suspension bridge over the Kali Gandaki river, then east into the Myagdi hills.

Before departing we did the math. The bridge was at 900 meters. Our high point four days later would be Mohare Danda (3300 meters), an ascent of 2400 meters (almost 8,000 ft) on trails marked “Steep Slope” on the map. Steep indeed! And we realized as early as Day-2 that this is not a trek for the faint of heart, lungs, or legs. No matter; we took it in stride, so to say, carrying our day-packs, chatting with villagers along the way, and taking many photographs.

For a peaceful and stunningly beautiful hike through the mid-hills (‘mountains’, really), this is it. Sometimes the well worn stone steps skirted towering cliffs, but more often we walked through dense forest, easy on our feet. And rhododendrons? Everywhere! Whole mountainsides of them. Millions of scarlet and pink blooms, punctuated by delicate orchids, deeply scented white lokta (daphne) blossoms and others.

Banskharka was the first day’s goal. This Magar ethnic village hugs a mountainside at slightly over 1500m elevation (about 5,000 ft) a few miles north and slightly higher than Mallaj, a caste village. Mallaj was once the center of a principality that predated the Gurkha Conquest and the unification of Nepal in the 1700s AD. A descendant of the last ‘king’ of Mallaj is now renovating the historic ancestral palace.

Banskharka was the first day’s goal. This Magar ethnic village hugs a mountainside at slightly over 1500m elevation (about 5,000 ft) a few miles north and slightly higher than Mallaj, a caste village. Mallaj was once the center of a principality that predated the Gurkha Conquest and the unification of Nepal in the 1700s AD. A descendant of the last ‘king’ of Mallaj is now renovating the historic ancestral palace.

In lower Banskharka, we were greeted by several young women out enjoying the sun in their courtyard. In the spirit of rural hospitality they served us glasses of cool, refreshing buttermilk (‘moi’). Like cold water (‘chiso pani’), moi is traditionally offered free to thirsty travelers. It beats Coke or Gatorade!

Then the trail continued on up through orchards of tangerine-like suntala (orange) trees beginning to bud to Banskharka Community Lodge. The lodge sits out on an open knoll with a panoramic view of Niligiri and of the sheer south face of Dhaulagiri. While we gawked at the peaks, our courteous hosts served cold drinks.

The lodge has a central dining hall, a kitchen and washroom. But as this is a home-stay village, we spent the night in a traditional old village house slightly modified for foreign guests. The rooms were small but neat, and the beds were made up with clean sheets and blankets. There was a water spigot outside for bathing, and a clean charpi (toilet) out back.

That evening after dinner we ambled back to our rooms in the twilight. Village women softly singing Hindu religious songs in a nearby house lulled us to sleep.

The following morning we continued on and up. In the Myagdi forests we passed several ancestral shrines called ‘bhumi than’, dedicated to the ancestors and honoring fertility and Mother Earth. About noon we reached Dandakateri Community Lodge for our mid-day meal.

Nangi was now visible across the valley and, as we continued on through farms and fields, we were warmly greeted by the locals. It was here that we began to feel the inner harmony of the place, and the creative spirit of progressive development.

Volunteering in Nangi

We stayed two nights at Nangi. The village is spread out facing west, with 126 houses and around 700 inhabitants, five schools (elementary to higher secondary), a community library with 5,000 titles, and many projects. The village center is on the brow of a hill facing the snow peaks, with impressive views. After checking in at the lodge, we took hot showers (solar heated, installed by volunteers), dressed in clean clothes, and set off to see some of the projects and volunteer activities.

At the school we watched a computer programming class for older students. Their teacher, Kushan Pun, was one of the first to learn computer science from Mahabir Pun in the 1990s. His students may go for higher education in Pokhara or Kathmandu, and can use their IT skills in almost any profession they choose, he said. Some will undoubtedly, as he did, teach in one of the newly wired village schools.

That afternoon we also met several of the foreign volunteers. A young Israeli proudly showed us the Community Trail website she was setting up. A French woman was working with the female health workers. And a half dozen education students had just arrived from England to help in the schools.

There are many opportunities for volunteers here, on such income-generating projects as paper-making, raising rabbits, fish farming, fruit farming, growing mushrooms, bee-keeping, jam making, cheese-making, yak farming and yak-cow cross breeding (Mohare and Khopra), and woolen bag weaving. There are also trekkers’ campground and community lodges to help manage, some with dormitories and others with adjacent home-stays.

On trek, we enjoyed the services of three lodges and two home-stays. And at Nangi we ate the output of local projects, with plum jam on our pancakes, fresh cheese for snacks, and shitake mushrooms with dinner. New and creative ideas are changing how things are done in Nangi and neighboring villages. But, while the locals are embracing the modern world they still preserve age-old ethnic traditions.

Barbara was so impressed by it all that when she returned home from the trek she developed a collaborative educational exchange program with the Himanchal Education Foundation. It will bring teachers from Myagdi and the state of Colorado together on an innovative mutual learning initiative.

The Sacred Forest

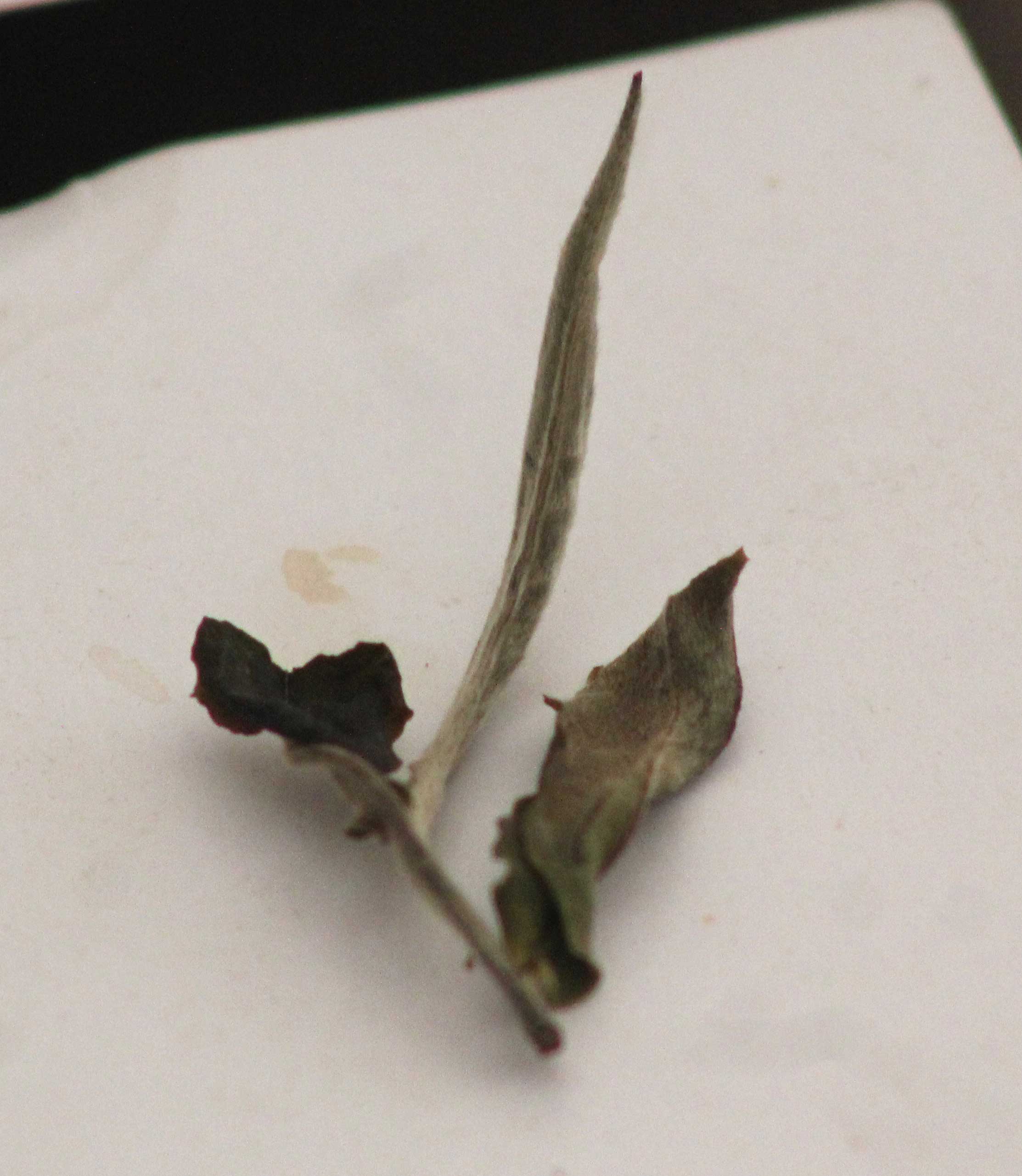

The next morning we set out to visit the forest called Barahi Patel. On the way up we visited a tree nursery where seedlings are grown for planting trees on farms and barren land. We also saw flowering lokta (Daphne bholua) and argali shrugs (Edgeworthia papyrifera). Traditional Nepali craft paper is made from lokta bark, and argali bark, known for its superior quality and strength, is exported to Japan and made into paper money, the Yen.

At the edge of the forest, we thought what a great place it was for children to explore. Then we remembered what Mahabir told us. As a boy, he said, he and his friends were strictly forbidden to violate the forest’s sanctity. The elders warned them: no peeing, farting, or defecating allowed. To this day, Barahi Patel remains remarkably pristine.

Deep inside the dense forest (‘patel’) we came to a cluster of small shrines in a glade where a small pokhari (pond) forms during the rainy season. On a full moon day in the monsoon, villagers come here to worship the goddess Barahi. Chitra talked to us in hushed tones out of respect for the sanctity of this awesome place. At the edge of the pond, he said, worshippers are met by a priest who serves as a medium to the deity.

They may ask him to help solve a problem, answer a vexing question, or honor a special request. With each request, the priest scoops up a handful of mud from the pond for the worshippers to take back to their home shrine. For example, a newly married couple may pray for a son. Then, once their wish is fulfilled, they come back up with the baby to thank the goddess and return the dried mud back to nature.

Kukur Chihan

On the way back down to Nangi, I asked Chitra about an intriguing name on the map west of the village: Kukur Chihan. Several decades ago, he explained, there were so many dogs in Nangi that the leaders held a mass extermination. The dogs were then taken to Kukur Chihan (‘Dog Cemetary’) for burial. Today, Nangi is dogless and uncannily quiet.

Mohare Danda

Early on Day-4 we set off for Mohare, up the Ripu Danda ridge trail through old growth forests of rhododendron, fir, hemlock and oak. At openings we looked out over a dramatically rough, hilly landscape 17 km SW to Pokhara. Near Mohare on a steep grassy hillside we saw a small herd of cattle, yaks and dzopa crossbreeds. Eventually they’ll provide milk for a future cheese factory.

At Mohare Danda (3300m) the map says: “Community Lodge. View of Sunrise. View of Dhaulagiri, Annapurna Himalayan Range and Pokhara Valley. Internet Station.” Barely a decade ago, this was a remote, windswept hilltop, with a few ragged trees and an empty meadow. Now it is festooned with electronic gear alongside the community lodge, porters’ dormitory and cattle sheds. The Internet is received here by line-of-sight from Pokhara then relayed on to surrounding villages. The popular trekkers’ destinations of Ghorepani and Poon Hill are barely three kilometers down a NE ridge on a little used trail.

When Mahabir set up his first receiver at Mohare to connect to the World Wide Web, some said it was an impossible goal. But he did it, striding confidently into the IT future. And now, while we admired his achievements, Mahabir (in Kathmandu) watched us by a webcam mounted overhead while chatting with us on Skype. After proving he could get online from such a remote and lonely place, he never looked back—, only forward. Mahabir Pun was Nepal’s first rural geek in cyberspace.

He didn’t do it alone, but had help and the good will of the local communities and foreign volunteers. The first volunteers read about him in October 2001on a BBC News website: ‘Village in the Clouds Embraces Computers’.

A doer, not a quitter

Mahabir Pun is the kind of guy who tries out an innovative idea and, if it works, he carries on, expanding the experiment. If it doesn’t work, he figures out what’s wrong and fixes it.

For example, the cheese factory in Paundar “failed at first,” he once told us. But that didn’t stop him. He simply closed it temporarily, sent the cheese maker off for more training, then reopened it successfully. Today, you can enjoy Paundar cheese in local lodges and guesthouses. Moral of the story: Mahabir Pun is a doer, not a quitter.

Raising yaks posed other problems, including hungry leopards and inexperience with high altitude livestock rearing. The management committee endured the initial losses at first, then made strategic improvements. Today, both the Mohare and Khopra yak and dzopa herds are flourishing.

The descent to Sikha

At Mohare Lodge, the friendliness, food and facilities were faultless. Next morning we awoke to an amazing sunrise panorama of the Annapurnas brightly lit up by the first bracing rays of Old Sol.

For many trekkers, the destination is Khopra yak farm on a high ridge at 3660m (12,008ft). But on our short trek, Mohare was the high point. From there, we set off down the NW ridge in the general direction of Sikha. Soon we met a gothalo (shepherd) and his cattle. We laughed when his little dog charged out at us, yapping furiously while simultaneously wagging his tail in ecstatic friendship.

Further along, Chitra showed us a stone pillar that marks the spot where, years ago, his ancestors had repelled a bitter enemy. The tall stone proudly reminds Magars of their prowess and noble heritage, he said. The territory west of the stone was successfully defended by the Magars, while the enemy retreated to the east.

Down we went through the dense rhododendron forest and across open meadows where cattle and buffalo herders spend the summer. And overhead, the icy Annapurna peaks hung over us, piercing the crystal clear blue sky.

For most of this day and the next we followed the Community Trail, marked by occasional blue and white stripes on trees to guide trekkers. We also noted a few old blazes on ancient tries. A century ago hardy hillsmen carried heavy loads of rice along here, heading north to barter for Tibetan rock salt near the border. In several stone shelters they took shelter from rain, and slept rough or huddled around smoky fires in the cold. Eventually the trail drops 8,000 feet down into the Kali Gandaki gorge where it joins the main north-south trans-Himalayan trade route.

About noon we broke out of the forest at Danda Kharka (literally, Ridge Pasture) at 2820m (9,250ft). The Danda Kharka Community Lodge sits in the midst of one of the most extensive rhododendron forests in all the Himalayas. We were so enamored with the ambiance that we decided to stay the night. After lunch we wandered the forest ablaze with rhodi blossoms, richly perfumed with flowering daphne, and alive with colorfully exotic birds. In this paradise for birders, I added ‘Mrs Gould’s sunbird’ and a female horned lark to my life list.

We chatted briefly with a group of Magar girls and boys passing through on a hike. They had recently completed their high school exams, they said, and were now out enjoying the freedom of the hills. Then an old man and his grandson entered the meadow leading a half dozen ponies carrying bags full of rich forest loam to be used as potting soil in their village tree nursery somewhere down the mountain.

Suddenly, while enjoying the laid back ambiance of the place, warning dark clouds rolled in over the hilltop, announced by a deafening crack of thunder and torrential downpour. As the temperature dropped, Hari Pun, the lodge manager, lit a fire in the wood stove of the dining hall for our comfort and served up hot, sweet milky tea while we marveled at the swift passage of the storm.

To Sikha

Most of the next day’s hike was on trails strewn with scarlet blossoms knocked down by the storm. The final approach to Sikha, however, was steep and required some deft route finding by our guide. From a place on the Community Trail called Naka, Chitra led us off down the mountainside and across an old landslide recently grown over by alder trees.

There’s a place in the alders called Ghaar Suna, he told us. It’s not marked on any map. The name means the sound (suna) of buzzing bee hives (ghaar). In spring when the bees swarm, the villagers place empty hives there hoping to attract the honey-makers, Chitra said. Traditional hives are made from stubby hollow logs with a small opening along the side. As they are colonized, the hives are carefully carried back down to the village and placed under farmhouse eaves.

By the time we reached Sikha our legs and knees were screaming from the abrupt 800 meter descent (over 2,600 ft). After checking into the private See You Lodge, we joined a group of Europeans in short pants outside having lunch. One minute we were all enjoying the afternoon sun, the next moment we were hit by a violent hail storm. When we ducked indoors to safety, the din of hail on the tin roof was deafening. Then, a quickly as it had come it passed, leaving only the fresh aroma of cold mountain air, forcing the Europeans to put long pants on.

The highlight of our afternoon at Sikha was our visit to the health post. There we were enthusiastically greeted by the Compounder, Kumar K.C., and the Health Committee Chairman, an ex-Gurkha soldier named Bag Bir. They and two nurses took us on a tour, proudly showing us the telemedicine hook-up that the Friends of Nepal had paid for. Then, with great dignity, they presented us with a formal Letter of Appreciation.

To Paundar and out

In the morning we set off to Paundar, our last Magar village. It’s on the side of a steep mountainside across from Sikha, part way up the trail to Khopra. There, we checked into a pleasant home-stay next to the school and village health post. A small group of volunteer doctors from Australia had also arrived and, while they held a clinic, we toured the school.

During recess, a teacher brought her small charges out onto the playground (the only level spot on the hill) to jump rope for exercise. At that, Barbara and Bill got into the act and introduced them to group jumps over a long rope. Great laughter. Great smiles. Great fun!

We also visited the cheese factory, then strolled the village lanes, up and down past traditional old stone houses with slate roofs. That evening Chitra was our chef. His pièce de résistance was curried rabbit with rice and sabji (vegetables).

On Day-8, our last on trek, our trail dropped sharply down into the Kali Gandaki canyon. Along the way, we met an innovative farmer who showed us the bee hives and bananas that provide him with a small cash income in addition to the rice, millet and corn he grows on astonishingly steep terraces. As we moved on, we watched as the morning sun moved with us down across the valley.

At Tato Pani we checked into Dhaulagiri Lodge, then went off to soak in the local hot springs. The next morning we boarded our ride back to the “real world”, to Pokhara. But, No. On second thought the real “real world” is back up there in the Myagdi hills and villages.

MAHABIR’S KUDOS & ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Mahabir’s accomplishments have not gone unnoticed. Largely based on his pioneering wireless project and his dreams for other, bigger developments in the future (a regional college, hydropower project, eco-resort, and more), Mahabir has received international recognition and several prestigious honors. The awards include:

• The prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award (often called the Asian Nobel Prize) given to Asian individuals who have achieved excellence in their respective fields (rmaf.org.ph);

• Recognition as an Ashoka Fellow, honoring social entrepreneurship and innovative solutions to social problems (ashoka.org); and

• An Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from the University of Nebraska (his alma mater), for “meritorious achievements and distinguished contributions to society” (unk.edu).

MORE ON VOLUNTEERING & TREKKING IN MYAGDI DISTRICT

After returning from trek, Barbara Monday, in collaboration with the Himanchal Education Foundation and iSCENE, the international Social Collaborative Exchange Network for Education (managed of the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational & Cultural Affairs), has planned a virtual learning project that connects teachers and students in Myagdi District with their counterparts in Colorado (USA). They’ll work together on science projects and curriculum development, including a trek along the Myagdi Ecotrail. For information contact Barbara at monday.barbara@gmail.com.

About the Himanchal Education Foundation, see himanchal.org.

For excerpts from Mahabir’s life see wirelessprophet.com; and on youtube.com search ‘Mahabir Pun’.

The Community Trail (Myagdi Ecotrail) website is nepaltrek.wix.com/nepalcommunitytrek. To plan an Ecotrail trek contact Chitra Pun, Community Trail coordinator, at chitra@himanchal.org.

Thanks to Mahabir Pun and Chitra Bahadur Tilija Pun for arranging and hosting a richly meaningful cultural trek, and to Rusty Brennan and Nima Sherpa of Ri Adventure Travels and Last Frontiers Trekking, respectively, for their logistical assistance. We especially appreciate the splendid hospitality of our hosts in each village. Two BBC news stories attracted the first volunteers to Nangi. See them on the Internet at news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1606580.stm and news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1615454.stm. And for more on the Sikha telemedicine link-up, an RPCV Friends of Nepal ‘Legacy Project’, see friendsofnepal.com.