‘Sirandala’ is what it sounded like. I never saw the name in print, for it is not marked on any map though it is a village of some consequence..., with a Lambardar (headman) whose jurisdiction extends over a wide area ? if ‘wide area’ is the way to describe a territory consisting mostly of near-vertical precipices. We were to receive much kindness at Sirandala. (Showell Styles, ‘The Moated Mountain’, 1955)

They were a strange-looking lot, four intrepid British mountaineers trekking through the mid-hills during the hot pre-monsoon of 1954. The white-skinned foreigners in shorts and shirts and a line of porters carrying tents and climbing gear were on trails where no such travelers had ever been before. Their leader was the jovial Showell Styles. Their goal was Baudha Himal, a 21,890-foot peak in central Gorkha District.

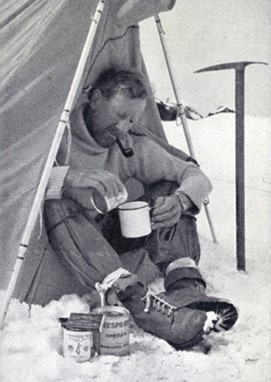

Less than a year after Hillary and Tenzing topped Mount Everest, mountaineering fever soared high amongst the British climbing fraternity. “Most British mountaineers, I suppose, dream of going someday to the greatest mountains in the world and attempting the ascent of an unclimbed peak,” writes Styles, mulling over the prospect of such a climb, he says, while sitting on a sleeping cow!

“To precious few of them is it given to convert vision into reality.”

Nonetheless, for this small expedition, little Baudha seemed an easy follow-up to the big one. Reflecting on the sanctity of Himalayan peaks, Styles goes on –

“If the Nepal Himalaya are indeed gods, and you picture them sitting in a row along the northern frontier with their long legs stretched straight out southward, you have a fair representation of the lie of the land across which our route lay. Baudha is far to the north-west of Kathmandu, and we had first to make a lot of westing, as the sailors say, before striking north; we had to march up and down across the bony shins of the mountains before we could gain the feet of Baudha and begin the upward climb to its head.”

With wry wit and irony, Styles tells his Baudha Himal adventure in ‘The Moated Mountain’ (1955). It’s a bad news/good news story, the ‘bad’ being they didn’t reach the summit. The same thing had happened four years earlier to his friend H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman and colleagues on nearby Annapurna-IV. In ‘Nepal Himalaya’ (1951), Tilman blames their failure on the “prosaic reason of inability to reach the top.” Styles could have made the same excuse but instead he gives us copious details about a set of impassable, ice-bound geophysical defenses they encountered, which made the peak impregnable, much as moats around medieval English castles protect them from attack.

The good news is that despite the failure, Styles also tells a little-known story about the team’s stopover in a small village they called “Sirandala” (Sirandanda). The locals still talk about that visit.

Baudha Himal is one of the smallest of five peaks rising along a line running northwesterly from central Gorkha District to the Tibet border. Manaslu, at 26,782 feet elevation, is the highest of them and eighth highest in the world. Himal Chuli and Nadi (formerly known as Peak 29) are both slightly over 25,800 feet. Baudha, as Himal Chuli’s little sister, anchors the south end of the range like an icy sentinel. The east side of the range drains into the Buddhi Gandaki River and the west into the Marsyangdi River, while the south side of Baudha is drained by two Marsyangdi River tributaries, the Chepe and the “Darondi” (Daraudi).

Baudha Himal is one of the smallest of five peaks rising along a line running northwesterly from central Gorkha District to the Tibet border. Manaslu, at 26,782 feet elevation, is the highest of them and eighth highest in the world. Himal Chuli and Nadi (formerly known as Peak 29) are both slightly over 25,800 feet. Baudha, as Himal Chuli’s little sister, anchors the south end of the range like an icy sentinel. The east side of the range drains into the Buddhi Gandaki River and the west into the Marsyangdi River, while the south side of Baudha is drained by two Marsyangdi River tributaries, the Chepe and the “Darondi” (Daraudi).

In 2015, the ground under Baudha was jolted by the great Gorkha Earthquake, a severe 7.8 magnitude seismic disaster. Villages on the hills below the peak suffered major damage. Within seconds houses, schools, and whole villages crumbled, and landslides roared down the hills leaving raw scars on the landscape.

Earthquake recovery and redevelopment brought me to Gorkha that year and again in October 2017 with the non-profit Gorkha Foundation. To date, the Foundation has rebuilt 20 of the more than 200 schools destroyed by the quake. In October, I documented construction progress and helped my companions demonstrate dental hygiene and other health practices to school children.

On our last day in the district we trekked up to Sirandanda. I was personally keen on seeing the storied village and hearing what memories about the British visit, if any, still linger. I also wanted to find the old headman’s house and meet descendants of the man whom the Brits described as a “most generous host.”

The 1954 British expedition to Baudha Himal began in the heat of April. On their sixth day out, they reached the lower Daraudi River valley, and on the seventh they began ascending a long, steep ridge stretching north toward the snows. In ‘Moated Mountain,’ Styles describes the ridge as undulating for two marches up to the last little cluster of houses. Beyond that, where “the upheaved wilderness of the great peaks is entered,” he writes, “the ridge rears suddenly to 10,000 feet, a lance tilting at the eternal snows.” That last little cluster of houses was Sirandanda (elevation 6,528 ft.)

Today, rough seasonal roads crisscross the hills, but back then there were no motor roads and few settlements. Throughout their two-day march up the ridge Baudha “hovered intermittently above the northern mists” – a scene, he says, which “encouraged the sahibs, somewhat daunted the coolies, and cheered the Sherpas.” It was also a challenge, for the expedition was rapidly running out of food. And though they met a few woodsmen and villagers on the way up, they were not able to buy any food. Their last hope settled on the one last little village, high up on the ridge –

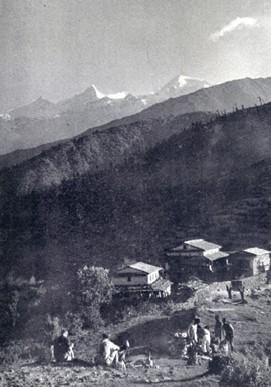

“We came to Sirandala early in the afternoon of the eighth day’s march. Its few houses were perched on a narrow saddle between two deep river-gorges, a most romantic situation. Had it not been for the amazing system of terracing, a man could have fallen for 3000 feet without pause into the Darondi Khola on the east, or rolled a little less speedily for 3000 feet into the Chepe Khola on the west.”

When the strangers were directed to the Lambardar’s house, they found “a fine affair of three stories tiled with stone slabs, dominated the half-dozen straw-thatched dwellings near it.” ‘Lambardar’ is an archaic Indian colonial term for what the Nepalis called, in those days, their “Mukhiya” (headman). (The hereditary Mukhiya system of village government functioned in the Nepal hills from the mid-1800s during Rana times until the 1970s when it was replaced by an electoral system.)

The Brits were greeted first by a dignified woman in traditional dress, impressively adorned with brass ear-discs three inches in diameter and bearing a wooden jug full of strong rakshi (alcoholic beverage) as a gesture of hospitality. The village women were “much given to personal adornment,” Styles writes. “Nose-jewels, necklaces, huge ear-rings, dozens of glass bangles, and a scarlet flower worn in the hair, went very well with their black garments and pale bronze skins.” The flowers were rhododendron blossoms, ablaze in the surrounding forests.

The Mukhiya himself arrived soon after, “a little wizened man who bowed before me with clasped hands and indicated that Sirandala and all in it were at our service,” says Styles. With such a warm welcome in this beautiful place, and the promise of ample food supplies available to purchase, the climbers decided to camp for the night. They found space on a knoll just wide enough for their tents, from which they looked down on the Mukhiya’s house and up to the snow peaks.

Within minutes Gyaltsen Sherpa was out foraging amongst the village houses. When he returned, he was “beaming with the news that many of the people here were Sherpas who had come from Solu Khumbu to settle.” The sahibs were assured that in Sirandanda they would receive “extra hospitality and ample supplies.” (We learned later that, today, 80 of today’s Sirandanda’s approximately 100 households are ethnic Tamang, while the remainder are Sherpa, whose ancestors migrated here several generations ago from Solu Khumbu below Mount Everest, over 200 miles east.)

In 1954, the arrival of foreigners in such a remote place was a momentous event. The Mukhiya remembered only one other, years before, a Bengali fellow who was undoubtedly part of the colonial Survey of India team in the 1920s. making the first maps of Nepal. “So, at last,” says Styles, “we were in country where Europeans had never set foot.”

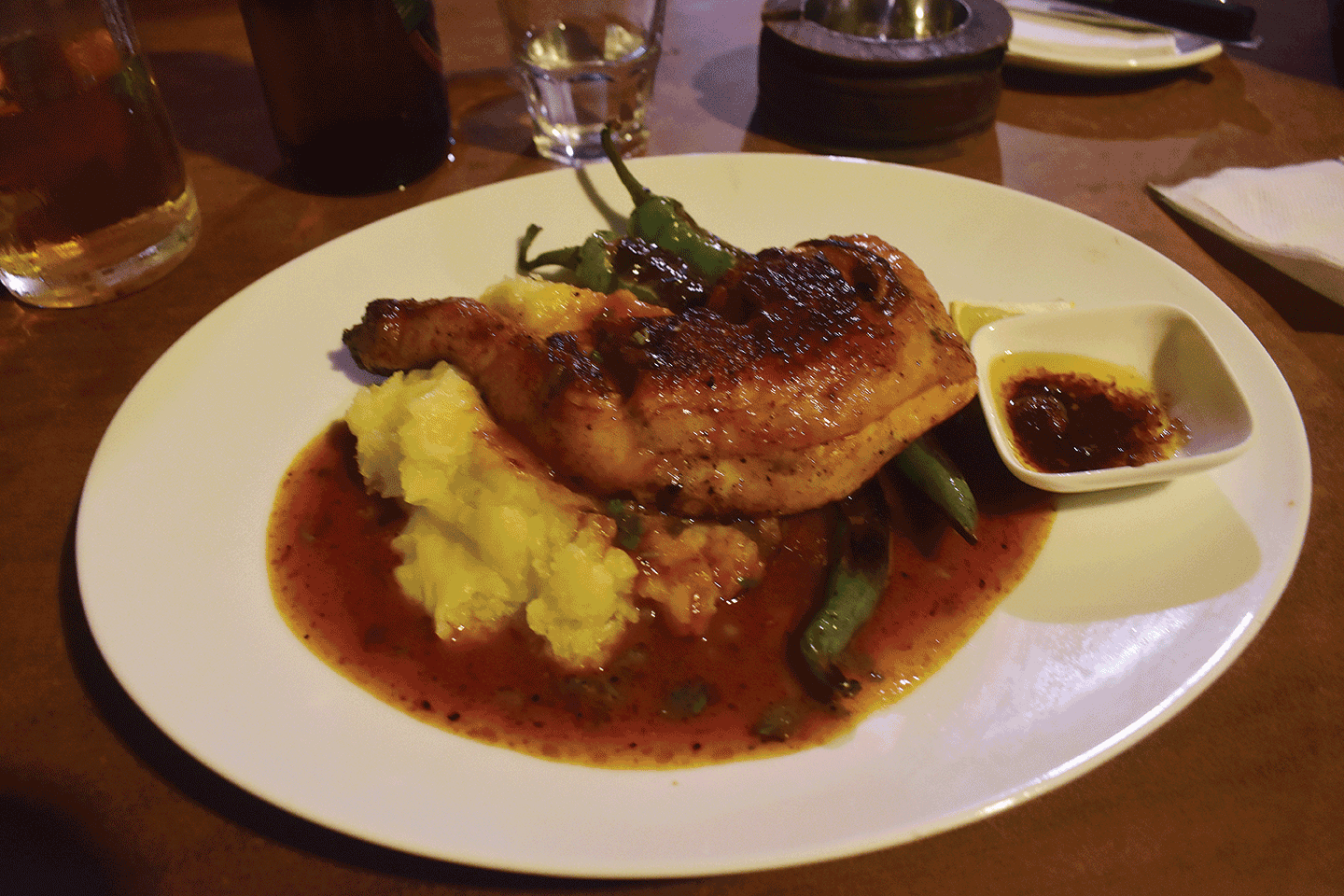

Nima Sherpa “cooked chicken and potatoes followed by rice and raisins for supper that night, while a curious but well-mannered throng of Sirandalans of all ages watched with all their eyes.” The chicken had cost them all of five rupees, and six fresh eggs cost them only one more rupee.

Savoring the genial hospitality of their hosts, the climbers stayed on for a second night to finish restocking the food supply and rest up for the climb ahead. All the while, “Baudha was veiled in cloud, and it was to be long before we got our next view of its mighty ice-dome.” On the third morning, as they prepared to continue up the mountain, all they saw above them was “a glittering powder of new-fallen snow.”

My interest in Baudha Himal and Sirandanda was first aroused in 1963 when I was living in the neighboring district of Lamjung with Peace Corps volunteers doing community development work. From our ‘dera’ (lodging) in Kunchha Bazar we had an unobstructed view of Baudha rising above the surrounding hills 25 miles northeast of us. When I found a copy of ‘The Moated Mountain’ for sale in Kathmandu I bought it for a pittance and read it in a day. It fired my imagination, but it would be almost 55 years before I converted my vision into reality by going to Sirandanda.

During the 63 years since the Brits came here many other travelers have passed this way, so we were not the strangers we might have been. Sirandanda is on a popular trekking trail to Rupina La, a high pass at the east side of Himal Chuli. It is also the last village on a well-trodden pilgrim trail to Narte Pokhari and several other sacred lakes high up under the peaks.

Our morning walk went by quite leisurely. We took in the sights, including a small ethnic graveyard hidden in shrubbery atop the precipitous east side of the ridge. We chatted with locals walking the narrow roadway. And, after passing through the small, newly rebuilt village of Nemki, we arrived at the base of the final ascent to our goal. That’s where we discovered how the village got its name. In front of us was a true ‘siran-danda’ ? the ‘face of the ridge’ ? rising steeply up more than 600 stone steps to the top. Along the way we stopped to admire a small white Buddhist stupa, freshly painted and strung with prayer flags. And we walked through an archway with a sign in English welcoming visitors to Sirandanda.

Near the top of the ridge, we walked out to a lookout from which we had an awesome view of Barpak, a large Gurung village eight miles east of us across the upper Daraudi River canyon. Barpak had been devastated by the 2015 earthquake; the vast majority of houses and other buildings collapsed instantly into heaps of rubble. Through binoculars we could see many new houses with distinctive blue metal roofs, signifying its recovery was well under way.

Back on the trail I asked an old man for directions to the Mukhiya’s house. He smiled knowingly and pointed ahead to the ‘bhanjyang’ (saddle) atop the ridge. Farther along we passed an ancient Hindu pilgrims’ shrine, a small tea garden, and cardamom growing in a damp nullah.

It was a school day, so we saw no small children. Any other time they would have come running to see the strangers. A few local youths were bringing in the last of the rice crop, but many of the young men, we were told, were off working in the Persian Gulf, or were posted abroad with the British Gurkhas.

We stopped for tea at a guesthouse called ‘Senna’s Home,’ and chatted with Tulsa, the proprietor. She knew where the old Mukhiya had lived, then volunteered her uncle to take us there. “Follow me, and you can meet him,” she said, and within a minute we were at his garden gate. After I explained my interests and described Styles book, Prem Kumar Lama, “better known as Karma” he said, introduced himself as one of the Mukhiya’s three grandsons. “Come with me and I’ll show you where he lived.”

Minutes later a second grandson joined us. Suk Bahadur Lama explained that he was the eldest son of the Mukhiya’s eldest son, whom the British climbers had met. If the Mukhiya system were still running today, Suk Bahadur would have inherited the patrilineal headmanship from his father.

At the bhanjyang, Suk Bahadur pointed across the broad open space and with a sweep of his arm he said, “This is where the Mukhiya’s house was before it fell down in the earthquake. It used to cover this entire area.” I translated his Nepali to my companions. The only remnants left of it now were stacks of large flat stones we saw, from the walls, the roof, and the flagstones of the original courtyard. Suk Bahadur told us that the heavy slabs had been laboriously extracted generations ago, from cliffs on the steep east side of the ridge. Today, they (and many memories) are all that remain of the “fine affair of three stories tiled with stone slabs” that Styles had seen.

At the bhanjyang we met the third grandson, Min Bahadur Lama. He runs a small shop there stocked with snack foods, condiments, cigarettes, whisky, beer, and sodas, ready-made clothing, a few tools, utensils, and the like. From the edge of the bhanjyang behind his shop the slope drops off steeply toward the Chepe River, a thin ribbon of water far below. I recalled how impressed Showell Styles was with the steep slopes and how, with a trace of poetic license, he visualized if someone tumbled off the ridge they might roll the whole 3,000 feet to the valley bottom.

I turned back to the flat, wide space in front of the shop thinking it would make a fine playground. But if children came here to play kickball after school, they’d have to be quick to catch the ball before it soared off into the void.

Recalling Styles description of it all, I told my companions –

“This is where the Mukhiya and his family lived. This is where the day-to-day business of running the village was conducted. And this is where the Mukhiya and his wife with the red rhododendron blossoms in her hair hosted their British guests over six decades ago.”

Of the three cousins, only Karma, the eldest, had faint childhood memories of the visitors. Most everyone else in the village has heard about them from oral tradition deeply embedded in local lore and legend.

We lingered there talking and taking photographs into the early afternoon before we reluctantly bid our new friends goodbye and turned back towards Senna’s Home where I had asked Tulsa to prepare us a late lunch. Karma joined us as far as his house. As we walked, I asked him if we could buy some ‘tej paat’ (cinnamon leaves) in the village. Tej paat is used like bay leaf in curries. The Gorkha hills are well known for its cinnamon, which is sold in Kathmandu’s Asan spice bazar. The aromatic bark sticks are commonly used to enhance the flavor of sweet tea.

Karma nodded and said we could have as many leaves from his tree as we wanted. At his hillside garden he opened the gate, dashed down the slope, lopped a large limb off the tree with his khukri, and with the help of some of our group plucked and stuffed fresh leaves into bags for us to take back to friends in Kathmandu.

When we asked what we owed him, he replied, “I’m a poor man. My heart feels good giving you this.”

We’d seen fresh cardamom pods laid out on mats to dry in the sun, and when someone asked how cardamom was grown, harvested and marketed, one of Karma’s neighbors gave us samples in the same spirit of generosity.

We thanked them both, then retired to the guesthouse where we snacked on hard boiled eggs, chapattis, and spicy spinach. The cheerful Tulsa brought a bottle out of the back room and with a proud smile poured us small glasses of a sweet plum cordial she had made. That elixir of the gods was the most flavorful highlight our entire excursion.

That evening back down to where we were staying, remembering Karma’s magnanimity, we pondered what it meant to live in a small village such as Sirandanda. “It’s the sort of place where everyone immediately knows there is an ‘outsider’ in town, who is greeted with both curiosity and friendliness. In small rural places like this,” said Carol, speaking for our whole group, “everyone seems to know everyone else and to be related to whomever you are inquiring about.”

Thinking back on the rural American community where she herself had grown up, Carol concluded that –

“People stop whatever they are doing to help foreigners in their quest. Meeting strangers in places like this brings out the best in people. The locals answer the strangers’ questions and do not hesitate to give or do their best for you. Some things are universal. There’s a generosity of spirit and things like local produce are joyfully shared.”

A little over a month after they had started out on their adventure, the British mountaineers called it quits and two of them, with two Sherpas, started down ahead of the others to hire porters and prepare for the overland trip back to Kathmandu. The descent was harrowing and difficult. After 11 hours on the trail, Styles writes, “we came down at last to Sirandala, in a golden burst of evening sunshine. Rarely have I been more exhausted.” Immediately, mats were rolled out as they lay reclining in the Mukhiya’s yard, and women were sent running “hither and thither” until, presently, –

“a bowl of rakshi was brought to each of us with a large brass platter of roasted barley. Then the wizened Lambardar... invited us to the verandah of his house and we had more rakshi, this time with hot potatoes and chutney. Fatigue gave place to a sensation of utter peace, a sort of demi-Nirvana.”

That’s when Styles “noticed hazily that the females of the Lambardar’s household were all possessed of houri-like beauty,” a side-effect of the rakshi, “a dangerous beverage.”

Next morning one of the Sherpas set off back up the mountain with three village men to strike the last camp and carry down what remained of the expedition gear. When they returned two days later, however, all the generosity and good feelings in Sirandanda turned sour with the news that the tents in the high campsite had been pilfered. Much of the team’s spare clothing was gone, along with maps on loan from the Indian government, expedition papers, a few rupees, and a few food items.

The Mukhiya and his eldest son were outraged by the theft, seeing it as a serious affront to the foreign guests. Except for losing the maps and papers, however, Styles considered it more of a nuisance than a catastrophe. He was more concerned at the delay of yet another few days that sorting out this issue would cause.

Suspicion immediately fell on local herdsmen who were pasturing their cattle in the high meadows up under Baudha’s cold stare. To identify the culprits and make amends, the Mukhiya convened a boisterous court of inquiry in the main room of his big house. Styles describes the venue as –

“a dark low-ceilinged place, warm with the heat of ashes in the central fireplace and the bodies of the dozen or so people present. It smelled of woodsmoke and rakshi, a cauldron of which the Lambardar’s wife was brewing over the ashes and stirring with a short wooden pole.”

Before the rakshi was served, however, she brought a brass platter with bananas and boiled eggs for the sahibs. Then the Mukhiya, sitting cross-legged on the floor in front of them, began to harangue the crowd with forceful vigor, implicating the herdsmen, three of whom had been ordered down from the high pastures to represent all the herdsmen at the inquiry. Although Styles did not understand much that was said, he took careful note of body language, tone of voice, and crowd reactions to what transpired.

The Mukhiya, he writes, was –

“an impressive speaker, reminding me very strongly of a Welsh Methodist preacher. His voice rose in sudden emotional crescendos, fell again to a doomful monotone, lightened into normality only to make one jump with a sudden thunder of accusation. He was, I should say, a natural orator. The three herdsmen listened with close and serious attention to a speech which lasted well over ten minutes. In the pauses they all said ‘Aw!’ in such perfect unison that they might have been responding to a conductor’s baton.”

“Everyone was grave and quiet” during the inquiry, except for a few small children “who pottered unchecked across the floors of Justice wailing for pieces of chapati or staring embarrassingly into the faces of the munching sahibs.”

The proceedings droned on and on, back and forth, to an inconclusive end. After the senior herdsman loudly declared their innocence, they got up and left to return to the herds. By then, the sahibs, restless and uncomfortably stiff from sitting on the floor, also wanted to leave. But not until the Mukhiya concluded the dramatics with a solemn promise to return the stolen goods intact or compensate them in cash (though nothing came of it in the end).

Among the sahibs’ last memories of Sirandanda was a rowdy celebration with the locals concluding the expedition. The following morning in a hangover haze after imbibing too much high-octane rakshi?one of the penalties of leadership he called it?Styles vowed to forswear “rakshi” forever.

On leaving Sirandanda –

On leaving Sirandanda –

“There was no last glimpse of Baudha on the morning of our departure, and I was glad of that. One does not care to be reminded of long-ago hopes and visions, however faint and fond they may have been. In any case, the retreat from a Himalayan mountain is in itself an expedition which may produce trials and obstacles of its own.”

Within a year of publishing ‘The Moated Mountain,’ another witty British writer named W.E. Bowman published ‘The Ascent of Rum Doodle’ (1956), a hilarious mountaineering spoof. Rum Doodle is a fictitious mountain 40,000-½ feet high, located in an equally fictitious country called Yogistan (think Nepal!). But similarities between the plot of ‘Rum Doodle’ and some aspects of the Baudha Expedition’s mountaineering feats seem too much alike to ascribe them to chance. Was the plot of ‘Rum Doodle’ inspired by failure on ‘The Moated Mountain’? Surely Styles and Bowman knew each other and would have shared stories over drinks wherever mountaineers and writers hung out in London in those days. Read more about it in ‘A Himalayan Mystery?Solved?’ online at http://old.himalmag.com/component/content/article/4819-.

The author’s companions in Gorkha were David Comerford, Mark Karl, Carol Lauritzen, Andy Morang, Marie Rampton, and Cathy Webb, all from Oregon USA. Some of them contributed photos for this story. We also thank Suk Bahadur Lama for the photo scans of his grandparents and their big house in Sirandanda, Kapil Bisht for his help in arranging it, and Hans Messerschmidt for his graphic assistance.