If things are going wrong or the way you don’t want them to, and you would rather have them take a different course, don’t be upset. You can change the course of happenings through divine intervention, say experts in Hinduism. So when Prema, a Hindu by birth and an ardent practitioner of rituals, was advised by her astrologer to perform a lakh batti (literally means 100,000 lights) rite for a better future for her son and daughter-in-law in Australia, she obliged. She had little doubt that the rite would immensely benefit her migrating children in their quest to survive and struggle in an unfamiliar land.

“Since to every action there is a reaction, every karma bears fruit,” says Prof. Dirgha Raj Ghimire, a retired teacher of Sanskrit for 40 years at Tribhuwan University. “Even if you perform lakh batti rite with no particular desire good things will happen, and according to Shastras (scriptures), your place is secured in Heaven.”

“Since to every action there is a reaction, every karma bears fruit,” says Prof. Dirgha Raj Ghimire, a retired teacher of Sanskrit for 40 years at Tribhuwan University. “Even if you perform lakh batti rite with no particular desire good things will happen, and according to Shastras (scriptures), your place is secured in Heaven.”

Prema is happy that her son, Dron, and daughter-in-law, Juna, are leaving for

Australia. But she just wants to ensure that things are easier for them there, and that they achieve success in whatever they do.

Babu Ram Rijal, an Acharya (the equivalent of graduate) in Karmakanda (the science of rituals) says there are three kinds of karmas: kamya, nitya and nimitya. “That you came here to interview me is kamya karma; you interview people everyday as a part of your job is nitya karma; and you do it hoping to become an editor someday is nimitta karma,” he says, almost clearing my confusion. His second attempt snuffs out all the doubts. “Any work you do is kamya karma, if you do the same work everyday it becomes nitya karma and if you do it seeking something, it is nimitta karma.”

Then linking his karmic homily to the context, Rijal says, “Lakh batti rite can wash away impurities and bring about positive results out of all three karmas, if performed in conformity to the guidelines in scriptures.”

For Prema the rite becomes a nimitta karma, as she seeks well-being and progress of her son and daughter-in-law; but to happen, as Acharya Babu Ram Rijal said, things will have to be done following guidelines in the scriptures.

So, what is right way of performing the rite?

A night before the rite the battis are soaked in ghee or oil extracted from til (sesame) or mustard seed in an earthen pot. “These days people prefer sunflower oil over ghee, sesame or mustard oil,” says Rijal. “When I tell them only any of the three kinds of oils mentioned in scriptures are acceptable, they tell me instead that sunflower oil is refined and therefore purer than the other oils.”

“If they do not follow, I quit,” Rijal says. Prema was lucky—Rijal would think otherwise—that she didn’t ask him to conduct the rite, because she, too, had soaked the battis in sunflower oil! The battis, wringed strand by strand out of small blobs of cotton, are about three inches in length. Women used to make the battis at their homes; but these days, battis are easily available in market. Since everything had to be done immediately after her son was granted a visa to live and work in Australia, Prema had no options but to buy them.

The following day a priest, qualified in Karmakanda (the science of rituals) is called in to conduct the puja (religious rite). “These days, hosts do not care to verify the antecedents of their priests. The Hindu religious science has different branches, and Karmakanda is one of them,” says Rijal. If you don’t engage an expert to carry out the rite, the whole thing makes no sense. “It is just like getting a heart patient operated by an orthopedic surgeon. Chances are that you will end up inviting more problems, instead of solving them,” he says.

Once the ritual is over, the lights are kindled. As the battis are lighted, the hosts and their family and relatives crowd around the earthen pot, throw their hands closer to the flame and roll back to place over their closed eyes.

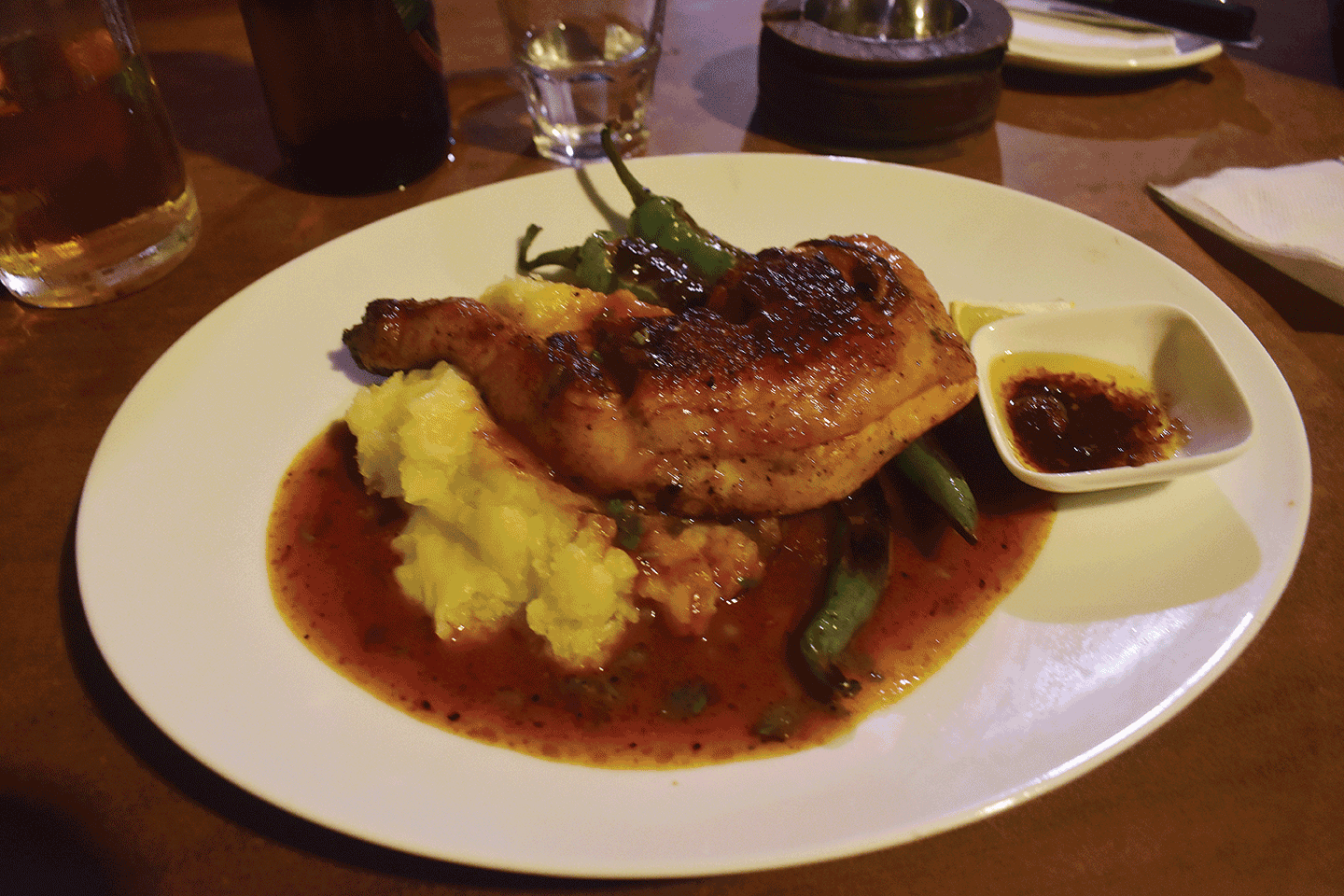

Thirteen Brahmans, including one vijnya (expert), should be fed at the end of the ritual. Relatives of the hosts who are invited to share the blessings, also join in the feasts later on.

The best months to perform lakh batti rites are Kartik, Magh and Baisakh of the Nepali

calendar. “Lakh batti performed during Kartik is 1000 percent more fruitful than other months. In Magh it yields 100 percent better results than in Kartik. Baisakh, however, is the most suitable month for a lakh batti rite as it produces best results—1000 percent more than Magh,” says Rijal.

“Lakh batti can cure problems related to eyes, even blindness,” says Prof. Ghimire. “While performing the rite we alight 100,000 battis. Logically, therefore, it heals all health problems that are in some ways related to body temperature. Almost every function of the body generally depends on temperature, therefore, the rite has overall benefits,” he says. Every matter has its dharma (essential character). Water quenches thirst, air carries oxygen, likewise, the dharma of fire is to aid in vision and anything that requires heat, he says.

Like most other ancient traditions, it is difficult to ascertain when or who started the lakh batti rite. Legend has it that Laxmana, an upper caste female, marries a lower caste male called Bhujanga soon after her husband dies. Poor and deeply aggrieved, she does so as she needs someone’s support to survive. Laxmana, however, feels guilt ridden for not keeping her widow’s chastity. One day she meets a hermit called Yajaka and asks ways to atone her transgression. The hermit tells her to perform a lakh barti (batti in Sanskrit) rite that cleanses all karmic doshas (blemishes) and opens doors of good fortune.

The scripture does mention that Laxmana and Bhujanga enjoyed great fortune and led happy life afterwards. If that is what you want, go for a lakh batti rite.

Some lesser-known vegetable dishes from the southern plains

I’m not a vegetarian but I love vegetables. And whenever I get to the southern plains of Nepal, I try...