Trek to Rara Lake, where you’ll be bedazzled by the sublime beauty of the crystal clear waters on which dances a million blue hues.

Often in moonless nights, it comes alive,” said the short-statured Gurung man we shared the bonfire with. He pointed at the clear sky above, and added, “We call it the White Rainbow.” Waiting restlessly for our dinner at the end of a tiring day having traversed along the glacier-fed Karnali River, we knew the streak overheard was anything but a rainbow. It was the Milky Way Galaxy; behind stars in their millions seen in the distinct clarity of night, and meteorites we lost count of that ripped through the hypnotic skies.

Often in moonless nights, it comes alive,” said the short-statured Gurung man we shared the bonfire with. He pointed at the clear sky above, and added, “We call it the White Rainbow.” Waiting restlessly for our dinner at the end of a tiring day having traversed along the glacier-fed Karnali River, we knew the streak overheard was anything but a rainbow. It was the Milky Way Galaxy; behind stars in their millions seen in the distinct clarity of night, and meteorites we lost count of that ripped through the hypnotic skies.

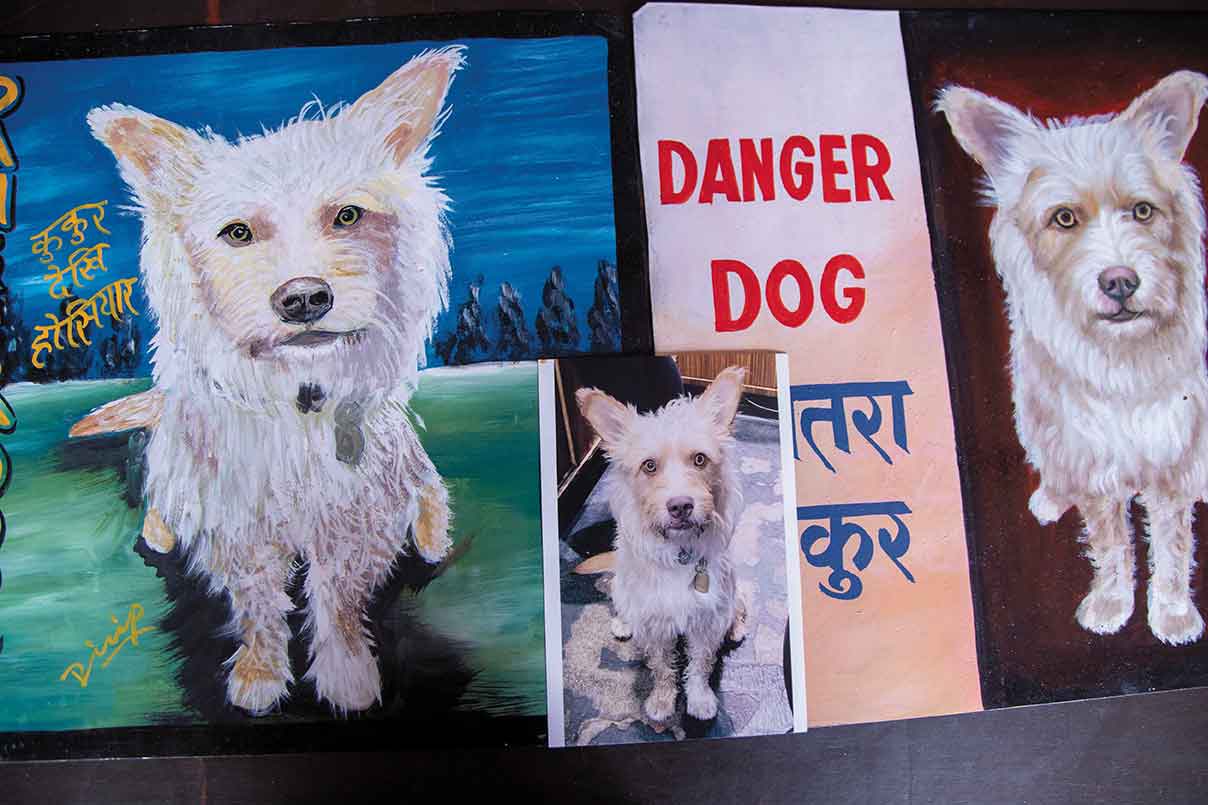

Our trek from Simikot to Rara Lake had started a couple of days before, with a humid and sweaty queue at Nepalgunj Airport where we queued up to board the first flight to Simikot. Having heard endlessly about the fabled trek over the years, it had made its way to a bucket list of sorts, conveniently above lesser nuptial goals. Upon landing in Simikot far west of Nepal, we were instantly breathing the freshest air we had in awhile. The tiny town on a cliff was surrounded by hills on one side and peaks on the other, across Karnali. As we walked down the market, we felt Simikot had a really friendly vibe to it, and people appeared too friendly to be true.

The trails we walked on were shared with old ladies headed to the market, and mules carrying heavy loads on their backs. Rice, salt, and apples, among other goods, for villages farther off. At the time of our trek, it was the season for apple harvesting, and we didn’t fail to turn heads and draw an offer for an apple. Ripe ones would go straight to the tummy, while raw ones went to dry in a bottle; some fantastic pickle in the making.

After passing several Magar villages for the first couple of days, we reached the tiny settlement called Sun Khada. At the base of our first tough pass (lek) at 3,600 m—mountains for us born-and-bred urbanites, mere hills for the locals—we’d look at the sky in amazement, and beat the night chill around a bonfire. We were promised a hotel by locals we met on the way. But, interestingly, this turned out to be the home of an elderly lady who let weary travelers crash in for a tiny fee. The nearest neighbors were at least a couple of hours away, which then made it possible for guests, not just trekkers like us, but also inhabitants of Humla and Mugu, to reach their destinations on long-haul treks. The stretch between Simikot and Rara is considered to be one of the most inaccessible places in Nepal, and can demand several days of walking to reach one’s destination. So, rooming with tired local travelers won’t be very surprising.

On this flawless night, the only guests the lady hosted were us and the short, garrulous, and short-statured Gurung man who was returning from Simikot after having seen his sister off. He, too, would be sharing the route with us the following day, and willingly volunteered to guide us to the lek. We prayed his navigation was not quite as iffy as his astronomical skills. We shared stories of life and travesties, while snotty children ran amok, dressed shabbily, which for a region as remote hasn’t fallen out of fashion. Our supper got cooked on a firewood stove, on utensils smoked and dented, probably decades old. Two hearty servings of rice and a soup of potato, fresh from the garden, got us early to bed. The hardwood planks that doubled as a bed came without warning, but we tried to get a good night’s sleep to wake up early next morning and make the pass.

Two days of trekking here was enough to drop our expectations of any facilities even remotely luxurious, like a toilet, for instance. Some houses do get due credit for having one, made obvious from a signage at their door reading: “We are proud to have a toilet in our home,” which, as comical as it was sad, reiterated the seclusion of this region. The house we crashed in wasn’t one of them, which meant nights called for a chilly and dodgy walk to the bushes, braving stinging nettles and strange insects. This made us appreciate our lives back home all the more.

Unlike a commercial lodge, our stay cost us barely anything, though the experience was quite out of this world in its own right. The old lady squinted at the two bills of hundred we handed her. “I can’t read,” she said, and stared hard at the money. “I have to look at the color to tell how

much it is.” Like many women her age in the region, she never went to school. In the dim lights before dawn, she craftily stashed her revenue in an improvised safe, a pressure cooker, and wished us well for the tough ascent. As we started walking, Gurung went on to explain how the region lacked medicinal knowledge, and explained about herbs they improvised to treat various maladies, including diarrhea and poor eyesight. “At altitudes this high, the vegetation is pristine, and there are ayurvedic experts who come up with natural potions,” he claimed. But, these claims seemed questionable when he attributed anti-carcinogenic properties to an arbitrary species of fungus we found on the way.

The climb was intimidating, and the ridge looked like it wouldn’t ever end. Amidst giant trees, we were shrunk to bite-sized chunks for bears we were told lurked in the dark corners of the woods. Blooming yellow flowers were incongruous to abandoned shacks used by travelers during winter time when it’d snow hard, and also our pit stops, to make the climb less daunting. Natural spring waters tasted like heaven, and made us utterly forget uphill woes. After two hours on wet trails, we finally reached the top to find ourselves rewarded with a bird’s eye view of tiny villages at the bottom and the might of Karnali that appeared like a trickling brooklet.

The intriguing culture throughout the trekking route was somewhat aboriginal indeed, which was most pronounced in the village of Simali. Women on a hot and sweaty day would casually walk about with their bosoms freely breathing air, unencumbered by social constructs. Kids, as small as five or six, would gallop on their tiny mules, returning from other townships and villages on finishing their deliveries. Most men, nonetheless, were mysteriously missing, which upon quick inquiry with other locals, revealed that Humla and Mugu are no exception to the problem of youth emigration.

Nepalis are generally quite inquisitive, perhaps intrusively so. While lunching at Simali, we were surrounded by a horde, and we, least of all, hadn’t expected a Spanish inquisition. “Are you paid to travel?” asked a male figure of the house where we ate. “How much do you earn from coming here?” another curious cat followed up. Their benign questions would be somewhat of an offence in cities. But, without further ado, they would go on, “How much did that camera cost?” Our usual lunch of millet bread and potatoes would be embellished with piercing questions. Several shameless servings later, we lay down on the floor, lulled and subdued, yet the questions didn’t stop: “How many children do you have?”

A few more leks followed, and the culture we experienced during the trek remained as pristine as the pure air; people, humble, and nature, untouched. I can’t say the same thing about a couple of villages that could clearly use some brooms and fly swatters. Towards the last stretch of the trek, signs of modernity became more evident, not excluding a hairstyle and guy-liner, inspired by Korean movies, on a bloke, welcoming us to Mugu’s capital Gamgadi. Huffing and puffing, we left the town’s commotion behind, marching towards Rara National Park just a stone’s throw away.

Two hours later, we found ourselves under the blunt glare of a soldier at the park entrance. “Dump everything from your bags onto the crate!” he ordered. It became obvious that they took security seriously at the park. Among our excited bunch was a father-son duo—locals looking for a quiet excursion—and goat herders on a quest for their runaway cattle. Also present was a visibly distraught group of red panda specialists conducting research on the endangered species’ habitat.

The final hours to Rara Lake took us through the park’s dense jungle. Veiled by the dense foliage, we could barely make out what hid behind until we reached the shore, and lo and behold, infinite shades of blue rippling across the lake. Reflections of the clouds danced on the surface of Rara Lake, and turquoise blended effortlessly to deepest azure. Unspoilt greenery abounded, and gulls soared above, while snowcapped peaks on the horizon complemented the serenity and beauty of the lake. We immediately proceeded to get our feet wet, until being asked sternly by authorities to step out of the water—water that was crystal clear, and in which fish could be seen wriggling through weeds, making the entire lake appear like an exotic aquarium. We settled in the quiet Danphe Hotel, overlooking Rara, and got a good night’s sleep.

It took us a fortnight of trekking on immaculately remote trails to reach Rara Lake, where, let alone tourists, even locals would be hard to find on the route; where legs got totaled, and egos tossed right out the window by grueling climbs under the unforgiving sun; where Rara’s glittering waters bedazzled Nepal’s far west, and made the million blue hues seem like a lucid dream come true.