A trek to one of Nepal’s last true wildernesses reveals it will remain so for a while.

Vultures came swooping down from the hill to the east, and I was reminded once again of my destination. I was in the army barracks in Jhigrana village, the last settlement before Khaptad National Park. My destination was the army barracks situated inside the park. Half a day’s continuous and arduous walk lay between the Elysian location and me. I was growing restless; the longer I stayed, the less chances I had of reaching Khaptad before dark. Under the gliding vultures and a few feet below me on the lawn, the lieutenant in-charge of the barracks and a few of his subordinates were playing cards. There were enough vultures around to make it appear like the men at the table were playing Russian roulette.

“You are going with our guest, aren’t you, Quartermaster Saab?” asked the lieutenant, without looking up from the cards he was studying. He had dealt a hard hand. The word “guest,” which denoted me, was a tough one to trump. Word had been sent to them from the Regional Army Headquarters that a guest was coming. The Quartermaster turned his head around to look at me. “Is it okay if we go tomorrow?” he asked. I don’t remember very well what it was that made me agree to his proposal, even though I had walked briskly for four hours to give myself enough time to make it to the Khaptad army barracks before nightfall. Perhaps I had sensed desperation in his voice, a plea from a man either losing greatly or on a winning run.

After watching the card game for a while I walked up a nearby hill to get a better view. A deer bolted as soon as I reached the top. On my way down I was spooked by a strange sound that came from a shelter built into the hillside. On closer inspection it turned out to be an old bunker where soldiers once slept. It had been turned into a pen now. The strange sound was of goats that had been locked in for the night. Coming down I met a soldier near the barracks. He told me he had come to look for me. He had waited for a long time for me to return from my walk. When I hadn’t, he had feared that I had fallen victim to the leopard that prowled the forest near the barracks.

No Nonsense Leopard

Later that evening, I went down to the village for a snack. I asked the lady running the teahouse if leopards were a threat to people or cattle in the village. I wanted to know whether leopards had killed anyone or anything in the past. “No,” she replied. Apparently, there was a pact between the people in Jhigrana and the leopard: The leopard kept to itself as long as certain rules were honored. “If certain rules are broken, then the leopard’s angry growl can be heard,” the lady said. One of the indiscretions that stirred the feline’s anger was menstruating women venturing into the area of the forest above the barracks. The leopard also growled displeasure if people created a clangor in the area. From her description, the leopard was more human than animal, a combination of a village elder with orthodox patriarchal beliefs, a punctilious army general obsessed with discipline, and a stringent forest officer.

The next morning I set off with three men – Quartermaster Ganesh K.C., and two soldiers, Gyanendra Khadka and Prem Pal – who were to ensure my safe passage to the Khaptad barracks. Near the top of a sapping climb a troop of langur monkeys dashed downhill a few meters ahead of us. Above us was a huge boulder, and Prem and I made the same conjecture about what could have caused such a fright. We walked to where we could see the boulder’s top, half-expecting to find a leopard basking in the winter sun.

After over an hour of plodding uphill we arrived at a clearing in the forest, a bog where the only sound was a gurgling stream. Gyanendra froze as we jumped over a rivulet. “I can smell something,” he said. He strained his sense of smell for a few seconds to identify the source of the odor. “It’s a leopard,” he declared. Not knowing what a leopard smelled like, none of us were able to corroborate or contradict, and so the feline whiff passed without further investigation. Maybe he was annoyed at this lack of support, for shortly after that Gyanendra began blaring music from his cell phone and kept it going for a while, turning folksong verses into an advancing army’s anthem. We had failed to smell what he had smelled, but now the entire forest was hearing what he liked to hear.

The fading light had already begun to turn the landscape grey and blue when we reached the first of Khaptad’s famed meadows. In one corner of this parched meadow was a round boulder, appearing like an installation art piece. In the opposite corner was a house built in memory of the victims of the freak snowstorm from over a decade ago. Four soldiers had frozen to death on the meadow, one of them my neighbor. The house was as much a memorial as a shelter to prevent similar tragedies from happening again.

No Hotel, No Shop,

No Politics

A short climb later we arrived at the point that marks the beginning of Khaptad proper, that tiny bit in the expanse of Khaptad National Park that has a few religious sites, the army barracks and the national park headquarters—the only place where there are people year round. Hillocks with round tops sprouted everywhere. A stream flowing through the center of this big open space made the only continuous sound. From the bustling forest we had arrived at a place so quiet it seemed to press on you the need for silence. The ‘WELCOME TO KHAPTAD’ sign that greets the visitor at Jhigrana ought to be placed here, I thought.

I also wondered how much meaning there was in that sign extending hospitality to visitors. In effect it was the same as saying ‘YOU ARE NOW ENTERING KHAPTAD NATIONAL PARK’—no invitation; just a plain fact. For all its natural beauty the place hadn’t a single lodge or even a teahouse. The only really modern thing in all of Khaptad was the army’s communication system and the satellite television at the barracks. To stay in Khaptad you either needed to carry your own tent and food or you needed to be, as I fortunately was, the guest of the Nepal Army.

The Question

Innocent questions and derisive remarks are a corollary to the announcement of a solo trek to Khaptad. “Lunatics go up there at this time of year,” my father stated when I asked him if I could borrow his motorbike to get to Silgadi, the hill town from where the trek to Khaptad begins. Almost everyone I met on the way asked me why I was going to Khaptad even when everyone knew that Khaptad was a place of great beauty. The cold, forlorn and remote Khaptad was not much of a destination for most. For me, it was a place where it was possible to steer away from all distractions, a place worth going to occasionally.

The Quartermaster had asked me the same question as soon as we had left the barracks at Jhigrana (by then I must have been more of a fellow-trekker than a guest). I told him I liked the quiet in Khaptad and was drawn to the Khaptad Baba, the holy man who had spent five decades in the wilderness there. I even told him my plan – it was more a hope since I needed permission from the army to do what I wanted – for this particular trip. “I would like to stay a night at the Khaptad Baba’s hermitage,” I told him. He responded with unexpected optimism. “You couldn’t have come at a better time,” he said. “Our Major Saab is a devotee of the Baba. He might even join you.”

An hour later I was enjoying the warmth of the Major’s privileged living room, sipping the most wonderful cup of black tea I can remember having had anywhere, and watching a newsreader narrate the details of a confrontation between the army headquarters in Kathmandu and some ministry. Major Rajesh Prasad Khatri turned off the T.V., partly to save power, which came from a diesel generator, and partly to save a state of mind that can only be nurtured in a place away from the worldly haggling. “So,” he said turning to me, “what brings you here at this time of year?” I told him. My first victory came when he smiled. The Major understands, I thought. He told me I could stay a night at the hermitage. I read Krakauer’s Into the Wild in bed. I was in one of Nepal’s great wildernesses. The following night I was going to be alone in the forest in a hut once occupied by a wise man. For some reason, I was convinced that the place would act as catalyst for a spiritual experience. A man had spent fifty years meditating in the same house. Surely, the place would have a profound effect on anyone who stayed in it.

Next morning I walked to the woods and the hill that everyone paid a visit to whenever they needed to make a private phone call (there was a phone in the Major’s office for official use). The hill was the nearest site from the barracks that had cell phone reception. I passed beaming soldiers, presumably returning from a chat with their lovers or wives. I sometimes saw Major Saab going to the hill. It was quite a sight. He would be accompanied by a small retinue, as though he was on his way to a parley with an adversary.

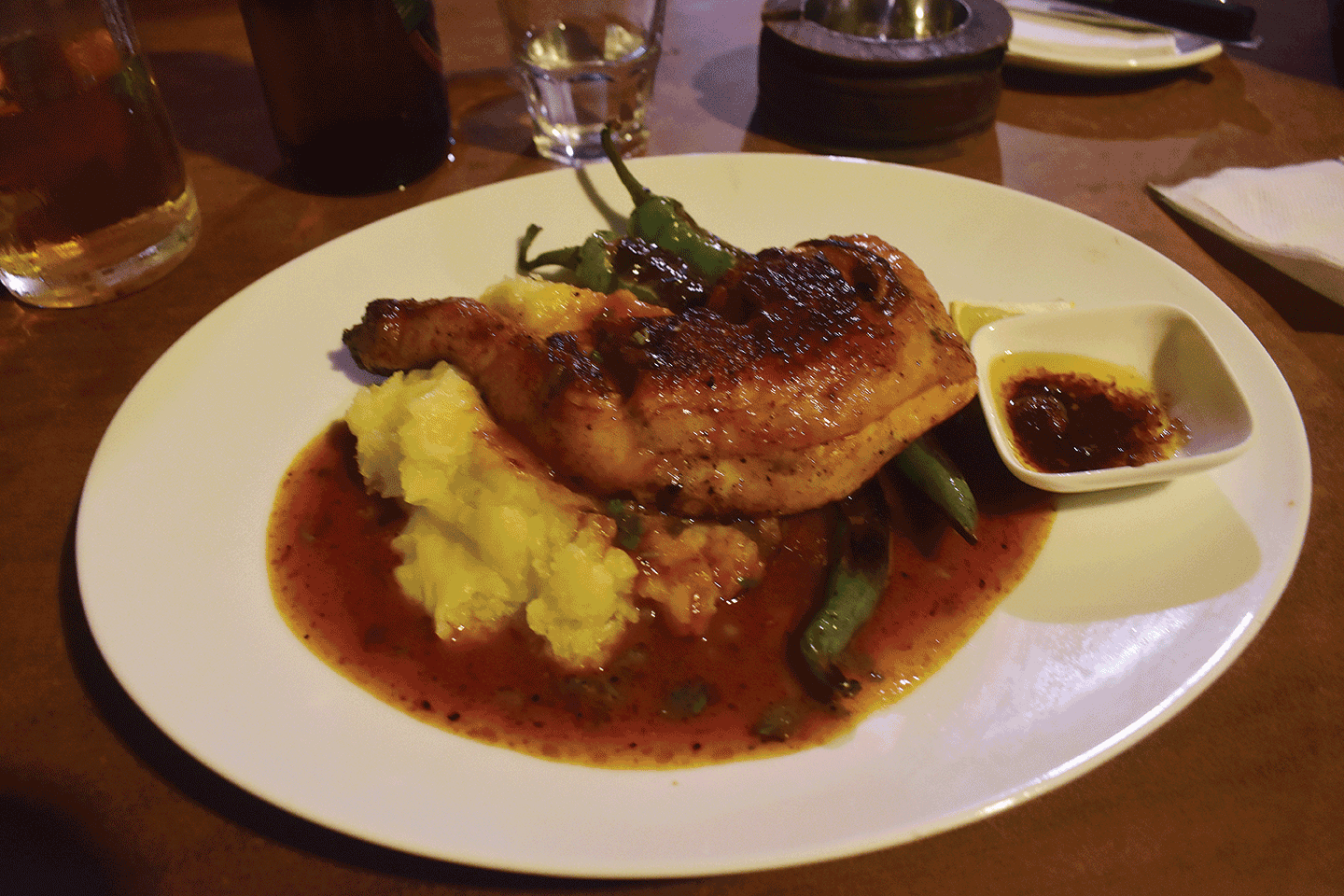

When I returned, we sat down to a breakfast of rotis, omelets, and reason. Major Saab gently served me a careful portion of this last item. “Wouldn’t it be the same if you spent an afternoon at the hermitage?” he asked. He put it to me tenderly but there was no mistaking its message: it was rhetorical. He had mulled my request over and had come to the conclusion that he couldn’t grant it. “The hermitage, we need to remember, is in the middle of the forest,” he explained. Animals were a threat. “Besides, I have no way of maintaining contact with you.” I reluctantly swallowed Major Saab’s reasons. I put on a composed face and told him I would visit the hermitage in the afternoon.

Holy Verandah

On the verandah of the wooden cottage was the bust of a man with a pink face covered in snow-white beard. A lovely smile lit up the face fashioned from concrete. The bust of the erstwhile occupant of the hermitage was now ensconced on a small wooden table. Paraphernalia such as a hand bell, conch shell, and a tika plate were neatly arranged beside the bust. To the south was a clearing, with a heli-pad in the center. Helicopters carrying the royal family and other influential people from Kathmandu once used to land on that ‘H’. The alphabet could easily have stood for ‘holy’, for this was a holy site, the Khaptad Baba’s hermitage. Passengers alighting from helicopters would have found an old man dressed in faded tangerine on the verandah. He had a radiant face and a child’s smile and curiosity. But that time had long passed. I found nothing but a deep silence, interspersed by the swishing of wind against the trees — just the kind of ambience the Khaptad Baba had sought. I had sought it too, but within minutes I was feeling uncomfortable in this primeval silence that would rupture at the sound of a parched leaf hitting the ground.

Although the Khaptad Baba was foremost an eremite, who had chosen Khaptad for the fact that he was guaranteed solitude (the Nepal Army arrived some three decades after the Khaptad Baba started living there), he enjoyed the company of people. The more diverse his interlocutors – monarchs, doctors, drivers – the more he relished the exchanges. My father remembers riding in a jeep once with Baba and a few other people. Baba had put one question after another about the vehicle to the driver. One of the men, a fervent admirer of the Baba, became irritated. Why did a wise man like him need to know about a jeep, he asked Baba. “There is no harm in accumulating knowledge on any subject or from any source,” replied Baba.

But there were certain topics he always avoided. “Ask me anything but my age” was the preamble to many conversations. I had heard people go on and on about how he had pulled a thorn out of a leopard’s paw, how a raven always followed him wherever he went and, most frequently of all, how he was well over a hundred years old, perhaps two hundred. But on that afternoon, sitting beside his bust, looking at clouds billowing in the deep blue sky, all the supernatural aspects attributed, much to his disappointment, to him ebbed away. I could only think of him as a man who had renounced worldly attachments and was diligently striving towards his spiritual goals, like those clouds that were not tethered to anything but still drifted toward some purpose. How could he have stayed here for over fifty years, I wondered, unable to comprehend the grit required to withstand the isolation. How did he manage to survive the harsh Khaptad winter? I inferred answers to such questions from his books, in which he reminds us that ‘if one’s thought is pure, what one considers as obstacles in the first place will eventually turn out as one’s aids’.

I left, having gained nothing more than the experience of a single afternoon similar (outwardly) to the thousands that made up the Khaptad Baba’s fifty years of solitude and single-minded search for Truth.

Another Recluse

There was one other man who had made Khaptad his home for a while now. I met him in the national park headquarters. Narayan Rupakheti was serving his third and last term as the warden of Khaptad National Park. I knew him from my first visit to Khaptad a few years ago. Since then I had come two more times. The army barracks had seen two companies come and go. The Warden remained, collecting information on the park’s plants and animals, writing reports and theses.

Rupakheti had an encyclopedic knowledge of all that grew, walked or flew inside the park. He knew where the newly-born wild dog cubs were, the place one was most likely to see Blood Pheasants, or which plant could be used to make incense or was an essential ingredient for making medicines for various ailments.

Khaptad National Park has always been the source of imaginations of all kinds. While the Khaptad Baba was around, it was about his age and his reasons for staying there. Today it’s about development. People see the snow-covered slopes of the hills of Khaptad and picture ski resorts. A hundred meters or so from where I sat listening to the Warden’s visions about the park’s future was the abandoned building that was meant to be Khaptad’s first hotel. Half of the ground floor of the circular building had been completed. Khaptad had fortuitously repelled back the advent of the outside world. The road that had been dug up the previous year from Silgadi to almost Jhigrana had been washed away by the first rains.

I arrived at the barracks to find Major Saab reading out a dictum to a soldier. The soldier was standing on a chair, paint and brush in hand, ready to put the wisdom on the wall of the guestroom. The words ‘KNOW YOUR ENEMY AND KNOW YOURSELF AND YOU CAN FIGHT A HUNDRED BATTLES WITHOUT DISASTER’ had found a wall but it would find no context in Khaptad. There was no enemy to know, no battles to fight here. The powerful silence of Khaptad and what an ascetic had achieved here inspired a benign and uplifting rendition of the same message: KNOW YOURSELF, AND YOU CAN FIGHT LIFE’S BATTLES WITHOUT DISASTER.

I knew Khaptad, knew that it was as fragile as it was beautiful. The specter, for me, of development loomed just beyond Khaptad’s boundary. The fear was undoubtedly a manifestation of the attachment I felt to the Khaptad that had no signs of development. I wanted it to remain that way, as though I owned it. But it was also based on what I had seen. When I first came to Khaptad there had been a hut where a man served simple meals. I had seen his hearth devour great logs. That shop no longer existed, but the image of that insatiable hearth lingered in my mind. I just couldn’t see Khaptad being able to sustain lodges, resorts, and crowds of tourists. It was for that reason that although the few hours in the hermitage had been memorable, I had got more pleasure on this trip seeing that incomplete hotel, roofless and at the mercy of Nature. It was, to me, a signboard stating emphatically: ‘VICTORY TO KHAPTAD!’