Sometimes you encounter strange and unexpected oddballs on the sidelines of history.

In December 1850, while returning home from their historic tour of Victorian England (the first by a Nepalese ruler), Prime Minister Jang Bahadur Rana and his two youngest brothers, Jagat Shamsher and Dhir Shamsher, along with an entourage of Nepalese officials, personal attendants and servants, met one of the oddballs during a brief stopover in Colombo, Ceylon. His name was Laurence Oliphant, the 21-year old son of colonial Ceylon’s Chief Justice. Laurence was invited to accompany Jang and party on their way home to Nepal.

After traveling and visiting Kathmandu as a Rana guest, Oliphant published ‘A Journey to Katmandu (The Capital of Napaul), with The Camp of Jung Bahadoor’ (1852).

Of Jang Bahadur he wrote –

“While smoking his evening pipe he used to talk with delight of his visit to Europe, looking back with regret on the gaieties of the English and French capitals, and recounting with admiration the wonders of civilization he had seen in those cities. He was loudest in his praise of England. This may have arisen from a wish to gratify his auditory [audience], and it certainly had that effect. He had not thought it necessary, however, to perfect himself in the language of either country beyond a few of what he considered the more important phrases. His stock consisted chiefly of—How do you do?—Very well, thank you—Will you sit down?—You are very pretty—which pithy sentences he used to rattle out with great volubility, fortunately not making an indiscriminate use of them.”

Of Jang’s two brothers, Dhir Shamsher captured Oliphant’s greatest attention. Dhir was his “particular friend” and “the youngest of Jang’s two fat brothers” –

“Colonel Dhere Shum Shere, such was his name, was the most jovial, light-hearted, and thoroughly unselfish being imaginable..., always anxious to please, and full of amusing conversation. ... [And he] was in his manner more thoroughly English than any native I ever knew.”

Dhir was someone –

“whose thoroughly frank and amiable disposition endeared him to every one, while his courage and daring commanded universal respect. I know of no one I would rather have by my side in a row than the young Colonel... Cheerful and lively, his merry laugh might be heard in the midst of a knot of his admirers, to whom he was relating some amusing anecdote, while his shrewd remarks were the result of keen observation, and proved his intellect to be by no means of a low order.”

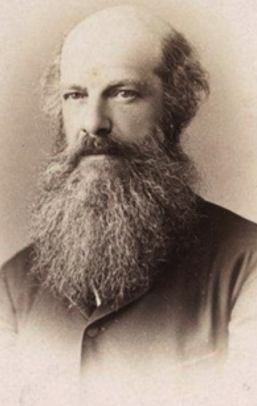

After Nepal, as a privileged member of British high society, Oliphant went on to live a veritable “mosaic of improbable adventures” around the world, first as a junior diplomat then as a war correspondent, barrister, spy, Member of Parliament, novelist, spiritualist and mystic. In 1879, he became known in high society for his satirical novel ‘Piccaddily: A Fragment of Contemporary Biography’ described at Goodreads.com as “One of the strangest books I have ever read...” It’s about a rich, vain, upper crust Englishman who thinks highly of himself and dabbles in off-piste religious fantasies. (It sounds biographical.) His most serious book was the spiritualistic ‘Sympneumata: Evolutionary Forces Now Active in Man’ (1885). Queen Victoria was said to have been impressed by it. Oliphant claims that his deceased wife, Alice Le Strange, ‘dictated’ it to him from the afterlife. (You can’t make this stuff up!) No wonder London’s Spectator magazine recently dubbed Oliphant as “the oddest of Victorian oddballs.”

Was he an oddball when he joined Jang Bahadur’s entourage from Colombo to Kathmandu? Probably not but we’ll never know, for no Nepali wrote about him.

After 1868, Oliphant was a member of the Brotherhood of the New Life, a group of Victorian Era mystics who believed that by deep meditative breathing one could communicate with angels and fairies. Upon his death in 1888 later, at age 59, Laurence joined his wife Alice in the hereafter where, perhaps, they met some of the angels and fairies they had contacted.

Sources: ● Laurence Oliphant’s A Journey to Kathmandu (1852); ● Bipin Adhikari’s ‘Laurence Oliphant on Jung Bahadur’ (a review), in Spotlight News Magazine (Kathmandu, December 28, 2012); ● Adam Stevenson’s of Oliphant’s ‘Piccadilly’ (a 2-star review) at www.goodreads.com; and ● Benjamin Beasley-Murray’s, ‘Laurence Oliphant: Oddest of Victorian oddballs’ (a review), in The Spectator (London, March 12, 2016).